The Ontario Historical Topographic Map Digitization Project: Past, Present, Future of Academic Map Libraries

About

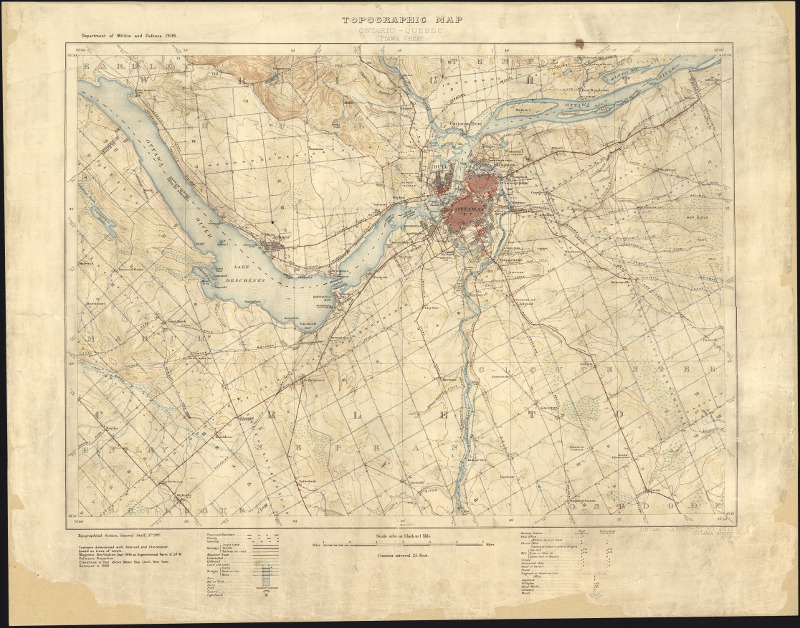

The Ontario Historical Topographic Map Digitization Project is a province-wide collaboration to inventory, digitize, georeference, and provide broad access to early topographic maps of Ontario. The initiative represents the single most comprehensive digitization project of the early National Topographic Series (NTS) map collection in Canada. This publicly-available collection provides access to georeferenced topographic maps at the 1:25000 and 1:63360 (one inch to one mile) scales, covering towns, cities, and rural areas in Ontario over the period of 1906 to 1977.

Maps in libraries

Have you ever visited the map collection at your local university, college, or reference library? Perhaps you were curious enough to open up one of the large format map drawers and rustle through them to find a particular map of interest—your Mother’s home town, the old cottage (and lake), or where you live today. Without taking an introductory course you may have realized rather quickly, ‘I might need some help with this!’. Providing access to maps in libraries has always been a ‘special’ area of expertise. Referred to colloquially as ‘special collections’, map libraries have often looked to increase their profile – whether to improve map discovery in the library’s catalog, or, battle for limited space in the library (maps can be large and take up a lot of space). Map libraries across Ontario contain thousands of maps to be discovered and reused, each one telling us a story about a time and a place, with beautiful colours and etchings and detailed features marked with expert classifications—called legends. The craft of cartography predates our modern view of the world – with Google Maps – both of which have had profound impacts on our understanding of space and place.

This story isn’t just about maps or map libraries, it is about a community of academic libraries in Ontario that face real challenges with managing print maps today. With more appetite for digital resources, map libraries are tackling digitization of print maps, air photos, and other geographic collections head on, and with sound best practices and processes that ensure access and reuse will endure well into the future. But what does it take to do this well, to represent geographic and large format materials in digital form? During the period of 2014 to 2017, the Ontario Council of University Libraries (OCUL) Geo Community [1] embarked on a project to digitize over 1000 historical topographic maps of Ontario using GIS and georeferencing techniques making them fully available on the web.

Digitizing the Ontario historical map collection

The story begins even before the dawn of digitization projects, starting around the early 1970’s with the OULC Map Group (now the OCUL Geo Community). Grappling with growing paper map collections, unknown overlaps across collections of university libraries, and no foreseeable mechanism for collaboration, the group devised of a union catalog for topographic maps, the first of many collaborative projects for this group. Building on the traditions of collaboration, by the late 2000’s the OCUL Geo Community as it is known today, decided to build a shared geospatial data repository. Launched in early 2012, Scholars GeoPortal provides access to geospatial datasets for researchers and the public. Its an understatement to say that the group actively fosters collaboration around maps and GIS in libraries to the benefit of researchers worldwide. In 2014, the group proposed the digitization of early editions of the non-standardized scales of the National Topographic Series maps, a rich resource heavily used in Canadian Map Libraries by researchers and the public at-large.

Starting with the Ontario maps, university libraries began analysing holdings across the province to produce a comprehensive inventory of all editions and years for the 1:25 000 and 1:63 360 scale series. Using Google Spreadsheets, students and library staff entered holdings information, status (e.g. digitized, georeferenced), and gathered information about the maps such as title, producer, edition (if stated), etc., which would later be reused to generate standard metadata (in ISO 19115 format) for each sheet. Cataloguing at the sheet-level for this collection had not been previously attempted, and so this was an opportunity to provide access to sheet-level metadata for the first time. Digitization was not an easy undertaking. With so many copies of maps in existence to choose from, and the variations in scanning techniques and tools, the group felt it was necessary to run through the gambit of testing and procedures to identify the best settings, standards, and dare I say students – to get the right scans. Yes, this project involved A TON of staff and student time to scan paper maps [2] . Each map scan was then properly reviewed for any mistakes with the image’s colour or skipped lines (sometimes causes the image to look like it has a line through it) that occurred during the scanning process.

Georeferencing a digital map can be a tedious process. Identifying stable ground control points for referencing and connecting to features found on a map (sometimes a river, road intersections, historical landmarks, etc.), takes time and expertise. Indeed the group did a lot of research to precisely identify the right amount of georeferenced points required to support online mapping and analysis without going overboard if you know what I mean. Students tirelessly georeferenced map, after map, after map, until all 1000 or so were completed. Since the digital collection consists of a variety of end products including high-resolution scans, georeferenced images for use in GIS, and web accessible maps for viewing, a lot of quality control had to be done to ensure the entire digital collection had consistent file naming, and all original and derivative copies were accounted for. Not saying we didn’t have a couple freak outs! This will also be extremely helpful when we embark on preserving these digital images for the long-term and adopt archival standards, such as LC BagIt.

Encourage use and reuse

Now who doesn’t like to see old maps online? Developing the fun and interactive map display and project website was really an opportunity to improve access to the collection by making maps easy to find, use, and access on the web. Together, the group discussed at length the many ways users might search for and interact with the maps, coming up with a flexible set of tools for accessing the collection.

Both this project and collection are exciting developments in the digitization and preservation of Ontario’s cultural heritage, and a celebration of the collaborative approaches of the OCUL Geo Community. It is timely that the project release date coincides with Canada’s 150th and OCUL’s 50th anniversary, so what better opportunity to reflect on our past, present, and future. And I can go on and on about the tremendous value this project has brought to the research community and the public at large, but I’m sure you can check it out for yourself – no introductory course needed!

For more information visit: http://ocul.on.ca/topomaps

Notes

- OCUL is a consortium of 21 University Libraries in Ontario, and fosters collaboration around library activities and services including map and GIS collections, digitization, and digital curation. Ontario’s university libraries have been working together through OCUL on initiatives such as this since 1967. In 2017, OCUL is celebrating its 50th anniversary.

- A full list of project contributors can be found on the project website.

Amber Leahey is the Data & GIS Librarian at Scholars Portal, the digital library project of the Ontario Council of University Libraries (OCUL). She can be reached at amber.leahey [at] utoronto.ca.