Learn about the benefits of constructing a multi-year internship from a MLIS student's perspective.

He reo e kōrerotia ana. He reo ka ora: Subject headings, a living language and Māori well-being

Ko tēnēi te mihi ki te tangata o te whenua nei. Karanga mai, mihi mai, karanga atu ra. I would like to acknowledge the traditional people of the land on which the Ontario Library Association offices sit.

Te reo Māori is an official language that is intended to be an integral part of everyday life across Aotearoa New Zealand: It’s a living language. Māori working in information institutions believe they share responsibility for language preservation and revitalization so have created initiatives such as Ngā Ūpoko Tukutuku (Māori subject headings). Our working team (Te Whakakaokao) develops subject headings from an indigenous worldview, in order to create “He reo e kōrerotia ana. He reo ka ora” (a living language) and strengthen Māori wellbeing.

Under the Māori Language Act of 1987, te reo Māori is not just an official language of New Zealand but is intended to be a spoken language and thus a “living language”: Widely spoken because it will be In common use within Māori whānau, homes and communities and appreciated widely by New Zealand society. (Te Puni Kōkiri and Te Taura Whiri i Te Reo Māori, 2003:5).

Over the past 30 years, many government institutions have adopted te reo Māori strategies and developed initiatives to support home and community language development. However, I believe that our communities must also keep our language alive, for the wellbeing of our mokopuna (grandchildren) and for our people: For four and more generations to come.

Te Wero: The challenge of two worldviews

Individuals from Te Rōpū Whakahau, Library and Information Association of New Zealand Aotearoa (LIANZA) and the National Library of New Zealand collaborated on Ngā Ūpoko Tukutuku. When the working group gathered, our challenge was to develop the first 500 terms for the Māori subject headings thesaurus under a framework that incorporated a Māori and cataloguing worldview.

Easy, right? Well, maybe not so much.

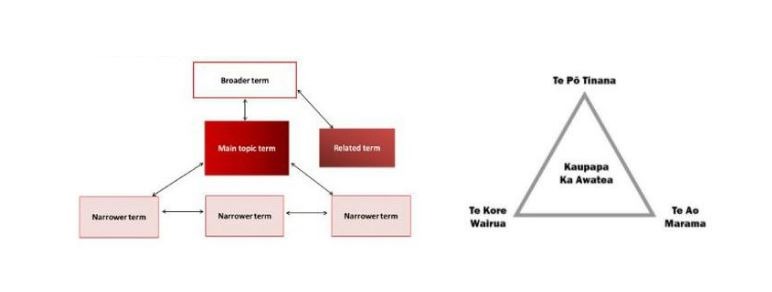

We needed three months, lots of discussion, post-it notes, and testing of different Māori paradigms but eventually we began to understand how the hierarchical structure of a thesaurus (left, above) might work with, if not complement, a Māori worldview (right, above)–kaupapa–in which we holistically acknowledge, perceive, and interpret the world.

Bringing these worldviews together, we realized that we had to think about Māori subject headings in terms of three dimensions:

- Wairua/Te Kore or the spiritual dimension of a word. We have to pinpoint its whakapapa and origin plus determine its relationships to different terms in the thesaurus. Whakapapa is “the act of layering one generation upon another, and the basic interconnectedness of all things. It is a continuous tradition of ancestry and inheritance binding the past and present” (Te Whiu, W. 2015).

- Hinengaro/Te Po or the intellectual and emotional aspects of a word to determine its standard definition, how it may be used in different iwi and examining thesaurus construction principles as set out by the International Organisation for standardisation.

- Tinana/Te Ao Marama or the physical dimension of time and space, which involves us (as people) and how te reo is being used in the world. The tinana aspect of a word examines context.

Mahia i te mahi/Doing the work

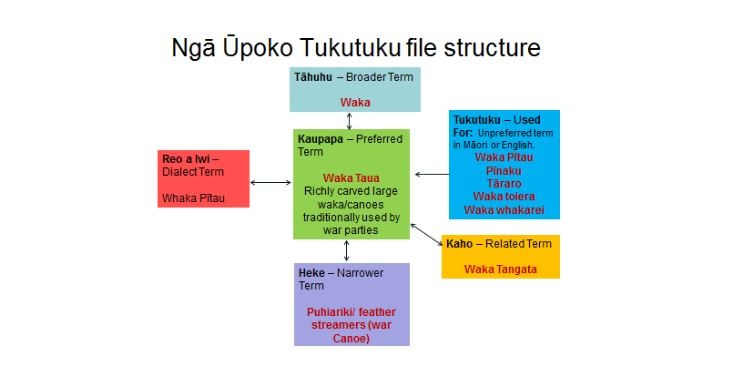

Using this approach, we created a file structure that contains a selection of Māori subject headings, defines their scope both in te reo Māori and English, and displays the broader and narrower terms between them.

To create terms, we take seven basic steps. For example, let’s say we wanted to develop a subject heading for war canoe:

- Start with the Kaupapa (the preferred term): War canoe.

- Determine an appropriate Māori term: Waka Taua.

- Identify its whakapapa: Where does it sit in the hierarchy and what is its broader term (the Tāhuhu): Waka (canoes, boats, transport, vehicles).

- Identify the narrower terms (the Heke): Puhiariki (feather streamers that go on the waka taua).

- Determine if there are any related terms associated with the subject (the Kaho): Waka Tangata (although resembling a war canoe, the waka tangata carries people regardless of gender).

- Look at un-preferred terms in Māori (Tukutuku or Used for) terms in English. In this case waka taua has several:

- Waka Pītau – war-canoe with a figurehead representing the whole human figure

- Pīnaku – war canoe

- Tāraro – canoe adorned with plumes and carving

- Waka Toiera – carved stern and stem of a war canoe

- Waka Whakarei – carved canoe.

While these terms are recognized, the preferred term is Waka Taua.

7. Don’t forget Iwi dialects (Reo a Iwi). In this case, Whaka Pītau is a Ngāti Porou dialect for Waka pītau.

Onwards and upwards

Currently, there are six members of Te Whakakaokao (the Māori subject headings working group) and we continue to develop new Māori terms for the thesaurus. From the initial aim to add the first 500 terms, there are now just over 1,700 preferred terms, 730 Tukutuku (un-preferred) terms and 56 Reo-a-iwi (dialectal) terms added to the thesaurus. In 2016, we managed to finish the backlog of terms requested by libraries and are now working on new terms as they come up while also adding more information to scope notes as requested by cataloguing staff.

In our culture, we understand that all that we do comes from a higher enlightenment, that we stand in solidarity with our Atua (Gods), Iwi (tribe), hapū (sub-tribe), tūpuna (ancestors) and whanau (family) for the betterment of future generations. And so, what we do does make a difference no matter how small.

The issue is not creating new initiatives that will provide for the survival of our language and culture but rather to formulate frameworks that acknowledge and retain the integrity of an Indigenous worldview—just as is being done around the world in other territories such as Canada.

References

Mead, H.M., & Grove, N. (2003). Ngā pēpeha a ngā tīpuna: the sayings of the ancestors. Wellington: Victoria University Press.

Te Whakakaokao (Ngā Ūpoko Tukutuku Reo Māori Working Group). (2013). Māori Subject Headings Nga Ūpoko Tukutuku. Retrieved from http://mshupoko.natlib.govt.nz/mshupoko/index.htm

Written by Raewyn Paewai

Raewyn presented this paper for the Indigenous Matters section of the 2016 IFLA World Library and Information Conference. Read the full paper, published by IFLA. This work is available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0

Copyright © 2017 by Raewyn Paewai.

Photo credit (feature image and slider): Photo by Tim Foster on Unsplash

(Lake Rotoiti with the mountains in the distance)

Raewyn Paewai is a freelance researcher. She is a descendant of the Rangitane and Te Arawa Iwi/Tribes of Aotearoa/ New Zealand. She has been the Senior Librarian—Māori Research at the South Auckland Research Centre, and has been working in libraries for 21 years. Raewyn can be reached at rpaewai [at] gmail.com.