Learn about the benefits of constructing a multi-year internship from a MLIS student's perspective.

Inclusive librarianship: On whiteness

In my journey to understanding the intersections of culture, diversity and inclusion, I have found Isabel Espinal’s thinking on the concept of whiteness useful and transformative.

In her 2001 article “A new vocabulary for inclusive librarianship: Applying whiteness theory to our profession,” Isabel writes convincingly of the need to reframe our thinking about race in the workplace. As she points out, librarianship in North America is dominated by those of us marked as white and the racialization of the profession creates deep inequities amongst librarians and other library staff. In addition, this mindset influences and shapes the professional perspective on services, ranging from collections to the teaching of information literacy. The result can be that when we think we are being inclusive, we might very well not be.

I discovered Isabel’s work in my own research on culturally responsive teaching and recognized that her ideas can help us in a range of contexts to rethink issues of inclusion and service. So I reached out last summer, to see if she would be willing to share her thinking with Open Shelf readers. And I am very pleased that she accepted this invitation to join our community in this important conversation, one in which Canadian librarians such Maha Kumaran and Heather Cai are also engaged (their 2015 article analyzes foundational data on visible minority librarians in Canada).

This article is the first in a three-part series on whiteness, positionality and intersectionality. I have asked Isabel some questions, based in part on her original article, and she will answer these questions throughout the series. This first installment focuses on the concept of whiteness and its continued relevance to understanding power relations in librarianship.

I hope that you find our conversation as interesting and motivating as I do. And return in 2019 to read Isabel’s ideas about position(s) and intersection(s).

Martha Attridge Bufton

Editor-in-Chief, Open Shelf

Eighteen years ago, you identified the concept of whiteness as important to the discourse on race. Do you think this idea is still relevant and why?

Yes, of course. It’s still relevant and what’s great is that it is being much more widely discussed. There’s a community of people who are discussing this in libraries. A few years ago, I was approached by Dr. Nicole Cooke to do an update on the 2001 article. Even though it came at an inconvenient time—I was in the tail end of writing a dissertation—I accepted Dr. Cooke’s invitation. I was happy to see in my literature review many other articles since that time. I suggested in the update (written with Tonia Sutherland and Charlotte Roh), that the bibliography we now have on whiteness in librarianship be used as a learning tool, a kind of syllabus for librarians, I think in particular for white librarians who may not have awareness because they are the constant beneficiaries of whiteness. One way that whiteness functions is to become normative, that it is taken for granted, it is invisible and unnamed. I recently updated that bibliography (Whiteness in libraries [Espinal, 2018]) with a whole book on whiteness in librarianship that came out after our article was written.

As for librarians of colour, a focus on whiteness is very beneficial. I found this true for myself and I got a great response from librarians of colour. Today in spaces for librarians of colour, it is very common to hear discussions of whiteness as it plays it in our day to day work interactions. Twenty years back, we did not have spaces for discussions of whiteness per se. Librarians of colour got together to be with each other but often the conversation did not name whiteness as much as it does today.

So I titled my article “A new vocabulary for inclusive librarianship” because at that time whiteness was a new vocabulary word in librarianship, but now it’s not new. We also now have other useful vocabulary, words and concepts to help us in the quest for making librarianship a better profession for all demographics. One of the most useful concepts to me personally is “emotional labor.” I found myself doing this kind of labor, expending this kind of energy because of librarianship’s whiteness and yet not having back then any way to validate this work or name it. This phrase resonates with me because having to confront whiteness on a daily basis leads to many emotions within myself and it does for many librarians of colour, emotions that white librarians do not have to deal with in the workplace. It takes work to deal with these emotions. Emotional labor also resonates in how it describes the labor that is involved in dealing with the emotions of whites when we try to address our situations as librarians of colour. We have to deal with white anger and resistance, with white fragility, which is another useful vocabulary term that I know you will also be asking about.

It’s wonderful to have a concept that addresses all this extra work that librarians of colour have to do. And the term emotional labor also is used nowadays for other situations, such as the emotional labor that women across the racial spectrum are often doing, so this also related to another question you have about intersectionality. Over the many years not only as a librarian but even before as an undergraduate student and as a graduate student I found myself feeling very very tired. Emotional labor helps to explain why some of us might be so tired all the time. It’s not that there is something wrong with us but that we are actually doing a lot more work!

As for librarians of colour, a focus on whiteness is very beneficial. I found this true for myself and I got a great response from librarians of colour.

At this point I want to give a shout out to the young and younger generation of librarians of colour who have taken these words, these concepts and have fiercely, expertly and vulnerably run with them. I have been in spaces with these librarians and I have also kind of watched them from afar. And I have gotten a lot of inspiration from them. Some of them have chapters in the books Topographies of whiteness: Mapping whiteness in library and information science and Pushing the margins: Women of color and intersectionality in LIS.

Yes, it’s great to have this shared vocabulary now. But having the vocabulary and the words to name our experiences are not enough. We really need to use the awareness that the concepts bring to us. We need to take action that will improve the situations that this word, whiteness, points out. There are many areas that can be changed, too much to go into all the details here. For that I would say, go to the bibliography! From the very first articles I found, such as Warner’s 2001 article “Moving beyond whiteness in North American academic libraries,” writers on this topic have made great suggestions. In the update I wrote with Tonia Sutherland and Charlotte Roh, we also made some very specific suggestions for actions, so I encourage librarians to read it when it does come out this fall.

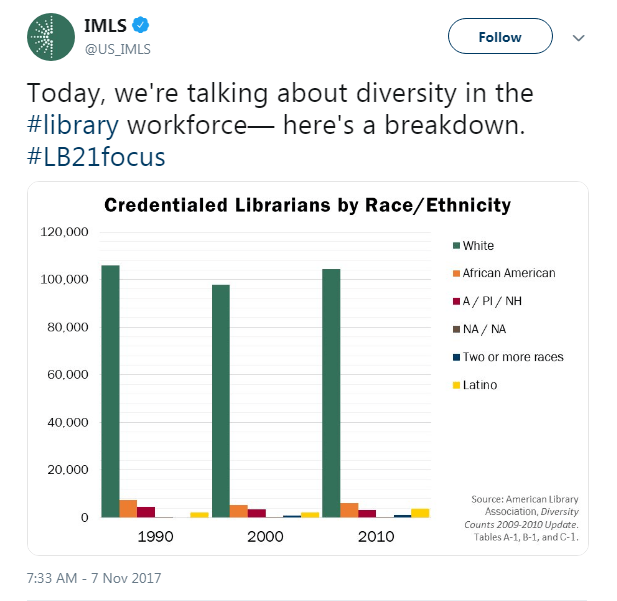

Right now, I’d like to focus in particular on one area, and that is the very demographics of librarianship and the demographics of library leadership in the U.S.A. and Canada. I don’t have numbers for Canada, but in the U.S.A., the profession is about 87% white and this number has hovered in this vicinity for decades. The Institute of Museum and Library Services tweeted a graph a year ago, November 2017 , that really hits the point that nothing has changed, despite decades of talk:

At this moment, I don’t think talking and awareness are enough. We really need to take more decisive actions to change this pattern, or we’ll be looking at these same numbers 20 and 30 years from now.

What kind of action? Well, I have actually developed a proposal that I am trying to get implemented at my own library. But I see that as something that many libraries can take on. I think that libraries can and should recruit more librarians of colour into the profession by recruiting among college graduates of colour and paying them to get their master’s degrees in library science while also providing part time jobs with benefits for the duration of their library studies. I’ve been presenting this idea at conferences such as ACRL New England and to individual librarians for the last few years.

Photo credit: Oliver Cole on Unsplash

Reference

Espinal, I. (2001). A new vocabulary for inclusive librarianship: Applying whiteness theory to our profession. In L. Castillo-Speed and the REFORMA National Conference Publications Committee (Eds.), The power of language/El poder de la palabra. Selected papers from the second REFORMA National Conference (p. 131-149). Eaglewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited.

Isabel Espinal (MLIS, PhD) is a Research Services Librarian at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, where she is the librarian for Afro American Studies, Latin American, Caribbean & Latinx Studies , Native American & Indigenous Studies, Spanish & Portuguese, and Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies.