The thinking of Comrade F. Dobler from the early 20th century remains relevant and even prescient: those who need open access to information may be those who are fundamentally excluded from public libraries.

Cultural appropriation

“No man is an island entire of itself.”

~ John Donne

Cultural appropriation is a “hot button” and deeply polarising issue that is being driven underground by political correctness: Some chose not to talk about it at all because of its potential toxicity; others have been fired from their jobs for voicing an opinion. But where do libraries stand in this debate? How do we square our mission to provide unfettered access to information with our duty to prevent the taking over of creative or artistic forms, themes or practices by one cultural group from another?

Community and culture

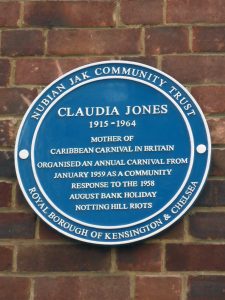

Context is everything of course. My starting point is that no culture can or should exist in a vacuum. All cultures knowingly and unknowingly borrow from each other. Cultures can and do blend and meld and take new forms while respecting and acknowledging where they came from in the first place. One of the best examples of this is what happened in the U.K. back in the late 1960s. The first wave of post war Caribbean immigrants faced extreme racism on their arrival in the U.K. Posters stating “No Blacks, No Irish, No Dogs” were routinely put up in boarding house windows. There were race riots in Notting Hill and Nottingham.

But then something amazing started to happen. The white working class youth started to adopt Jamaican culture. They were attracted by the fashion, style and music of their new neighbours. The lightning rod was reggae music. Record labels such as Trojan started to appeal directly to white working class youth, and the first generation of skinheads was born. These young men and women had a deep respect and affection for Jamaican reggae music and in the dance halls of London and Nottingham they would meet and mix with the sons and daughters of this culture.

The next stage of this process—a kind of reverse assimilation—was the adoption of Jamaican street language. The outcome was an accelerated integration process. Today the Jamaican diaspora—while still facing huge challenges from racism to unemployment—is deeply embedded in British society. In parts of the U.K, such as the St Anne’s estate in Nottingham, mixed heritage relationships are the norm.

And this happened not because of the state, which eventually got around to passing the first Race Relations Act in 1975, but because of the People, who started to mingle and adopt (appropriate?) each other’s cultures six years earlier in 1969.

So culture can play a huge role in creating common understanding, but this cannot work if one culture is hermetically sealed off from another. And it will not happen if we cannot even talk about cultural appropriation, what it is and what it means, without fear of reprisal. We should have an open debate in which libraries, as the collectors, conservers and conduits of culture, play a lead role.

We should be organizing discussions in our libraries and inviting speakers from all sides of the argument to contribute. And 2017 would be a great time to start this Big Conversation given the contentious nature of Canada 150.

Authors and appropriation

I recently attended a local author panel featuring three women writers from northwest Ontario. They were all white and what I would call middle class. One of them wrote fantasy fiction and created new worlds populated with new people. No cultural appropriation there. The other two chose to write about cultures and experiences that were far from their own. One of these books is about child soldiers in Africa viewed through the eyes of a young Ugandan boy. The other book features a young Métis boy whose father leads voyageurs into the northwest to trade with native people.

When I asked the cultural appropriation question, their defence was that their books were very well researched and that they had consulted with people from the cultures they were writing about to validate their work.

Is it cultural appropriation for white people to write about these subjects? Should these stories only be told by the people who belong to and fully understand these cultures? By writing about these subjects are white people denying a voice, and an income and livelihood, to indigenous peoples? These are the kind of questions we should be asking and the type of debates we should be having in our libraries.

Public libraries and politics

There is a pervading myth that public libraries are and should be neutral and apolitical. But in fact they are deeply political in many different ways. Every time we select, or decide not to select, a book we are making a political choice. Our stated mission is to provide unfettered access to information but in reality we practice self-censorship and we control what is available through internet filtering.

This all leads us back to the fundamental purpose of public libraries, which were founded in the mid-nineteenth century not as philanthropic agencies of social change, but as state institutions of social control. They continue to fulfil this role today, as part of the ideological superstructure that is determined and shaped by the capitalist economic base, but in much more nuanced and subtle ways.

John Pateman is the CEO of the Thunder Bay Public Library. He is also the author of the Open for All? column in Open Shelf.

This Post Has One Comment

Comments are closed.

Great article! I agree that we need to turn our attention from ie., rewarding the dominant cultures for speaking on behalf of oppressed cultures. I also agree that on a surface level, common understandings are important, but I also think we need to move beyond common understandings, and engage in discussions about multiple historic narratives and understandings – and really allow for the competing stories and identities to be seen and heard. If we are focusing on finding common understandings (which is not what you were arguing- just my thoughts), then we might inadvertently promote further marginalization because each social group will care more about its own culture and put aside concerns about the unequal power structures. In this way, I think that if we can shift the responsibility from the individual or the socializing group as the point of analysis, and look to the political contexts and interactions that create and continue inequalities, then maybe we can transform our imaginations. By merely researching and writing about another culture, this is denying the process of understanding the unequal power structures in society. Thanks for writing this!