Learn about the benefits of constructing a multi-year internship from a MLIS student's perspective.

60 years of service: First Nation public libraries in Ontario

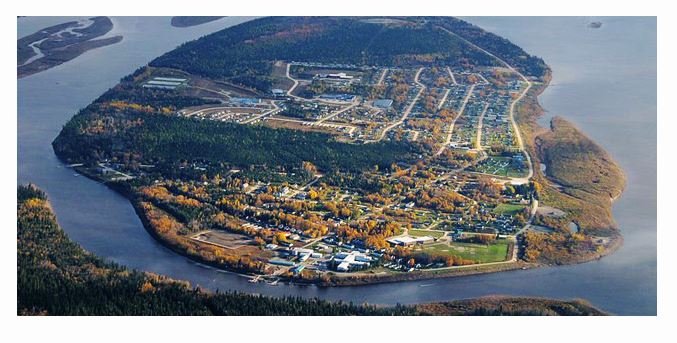

Moose Factory is a northern Cree community tucked in the Moose River off the southern James Bay coast. In 1959, the island community played a foundational role in the development of First Nation public libraries in Ontario: It became home to the second public library established in an Indigenous community in North America, the first being in the Colorado River Agency in Arizona. [1]

It’s been 60 years since Angus McGill Mowat (head of the Public Libraries Branch of the Ontario Department of Education) oversaw the completion of the Moose Factory First Nation public library, and this year we celebrate the contribution that First Nation libraries such as the one in Moose Factory make—past, present and future—to supporting and enriching the communities they serve.

Ontario is the only province in Canada that has publicly funded libraries in First Nation communities, and over the past six decades, the number of First Nation public libraries operating in the province has increased from one to 47. Of these libraries, 29 are operating in northern Ontario and 18 are operating in southern Ontario.

In 2004, to ensure that First Nation libraries would continue to thrive, a committee consisting of six First Nation librarians and three advisors from Ontario Library Service – North (OLS – North) and Southern Ontario Library Service (SOLS) released a document entitled Our Way Forward: A Strategic Plan for Ontario First Nation Public Libraries (2004–2009). The strategic plan had specific goals and objectives but the document also included a vision statement that timelessly encompasses the essence of First Nation public libraries:

Public libraries provide an essential service to First Nation communities. Our Chiefs and Councils lead our communities in recognizing and supporting our public libraries as vital contributors to growth and change. With current and culturally relevant collections and services, First Nation public libraries welcome all community members and support their needs for access to information, personal empowerment and self-affirmation. In partnership with other community programs, our public libraries contribute to our social and economic well being by nurturing our spirits, preserving our traditions, cultures and languages, and encouraging lifelong learning and literacy.

In this vision statement, a key idea that actively guides library staff today is “in partnership with other community programs.” This idea means a library may partner with other essential band office departments such as the health, the education and the early years departments to engage in mutual goals such as language revitalization and cultural revitalization.

In the past 60 years, there have been many success stories of partnerships that have led to renovated libraries, new public programs, and significant collaborations with outside stakeholders. Plus, community members are actively using their libraries. According to the 2017 Ontario Annual Survey of Public Libraries results, there were 7,704 active library cardholders registered in First Nation public libraries.

Many libraries operate on a large scale with limited funding and resources. OLS – North and SOLS offer First Nation librarians assistance with marketing, grants, partnership opportunities, website development, collection development and general advice. The service organizations also provide multiple annual programs to enhance the librarians’ goals and visions. Some of the significant programs include:

- Annual Spring Gathering where librarians gather to learn and to participate in conference sessions and workshops

- First Nation Communities Read programs which highlight Indigenous authors and later distribute reading materials to First Nation libraries

- First Nations Public Library Week which takes place in October

- The Language Revitalization Portal on the OLS – North website

In the short time that I have worked for OLS – North as the Capacity Building Advisor, I have learned that the public libraries in First Nation communities are an essential service. The libraries are safe spaces for community members to gather and to learn, to discuss community histories, and to support the development and the growth of community members. I think a significant part of the success of each library is attributed to commitment of the librarians and to their engagement with the community.

In the spirit of librarianship, each librarian takes the time to participate in community events to understand public needs so the library can offer relevant services. Many libraries are focusing on cultural revitalization, language revitalization, collecting resources, researching, and providing programs and services that may be difficult for isolated communities to obtain.

Overall, I think that each librarian is a community role model, local historian, friend and education supporter. Certainly, librarians are helping to build the capacity needed for libraries to support communities for at least another 60 years.

If you would like to subscribe to Maaziniigan, which is a First Nation public library newsletter, please email dnebenionquit@olsn.ca.

Footnote [1] Edwards, B. (2005). Paper talk: A History of libraries, print culture, and Aboriginal peoples in Canada before 1960. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press.

Photo credits

Aerial shot of Moose Factory: Moose Cree First Nation

Sachigo Lake First Nation and Wabauskang First Nation Public Library: Deanna Nebenionquit

Deanna Nebenionquit is Anishinaabe from Atikameksheng Anishnawbek, formerly known as Whitefish Lake First Nation. Deanna is a graduate of the Applied Museum Studies program at Algonquin College in Ottawa, Ontario (2012) and a graduate of the RBC Aboriginal Training Program in Museum Practices at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Quebec (2013). Deanna can be reached at dnebenionquit [at] olsn.ca.