Helping others discover their familial roots had exposed an issue in my own family that I realized I needed to address: Finding my own roots.

Genealogy 101: So you’re a genealogy librarian. Now what?

As I shared in the first installment of my series, Genealogy 101, I had never really been interested in ancestry or in tracing family roots prior to becoming a genealogy librarian in 2016. With little or no training and a lack of knowledge of my own family roots, I felt frustrated and a little wistful when helping patrons with their genealogical queries. However, by using professional tools and standards, along with my own family as a case study, I am now much more comfortable in my role.

In this two-part second installment, I will share my own experience of learning, both formally and informally, how to become the genealogy specialist in my library.

Part I: Methods and tools of the trade

I used to feel frustrated when assisting patrons with their genealogical queries, partly because I lacked adequate training (both formal and informal). For over a decade as a public librarian, I have had more than one role:

- Children’s and teens’ librarian

- Adult services librarian

- Reference librarian

- Business and career services librarian

- Collection development librarian

Having had experience in so many subject areas, I became not quite a generalist but certainly a subject specialist with relatively deep knowledge in a variety of fields, with the exception of genealogy. When the offer came to take on genealogy, I welcomed it as an opportunity to become a more powerful librarian. Like any new subject matter specialization, genealogy is merely another subject to master. After all, that’s what we library folk do. We learn new things. We apply the same tenets of our work and posit them amongst new jargon and tools. However, I also realized I had not had enough training to feel comfortable in the role.

When librarians enter this new field, training and support is extremely important. As Carol Smallwood and Vera Gubnitskaia explain in Genealogy and the librarian (2018), digitization “trends on one hand are going to make it easier for librarianship, but on the other hand it is going to increase the responsibility of information providers such as librarians” (p. 6). After some knowledge transfer sessions with my genealogy team lead (thankfully, I had one!), I decided that using genealogical tools to trace my own family history could be a good strategy for acquiring the skills and the knowledge I needed for my new position. This approach would mimic the typical reference experience (for both librarian and patron), where both are united in trying to provide authentication of family stories via records; i.e., they are attempting to follow the Genealogical Proof Standard (GPS) to determine if family stories are “right.” Oftentimes, storytelling is our main means of understanding ourselves and our ancestors. But we don’t always know if the stories are true.

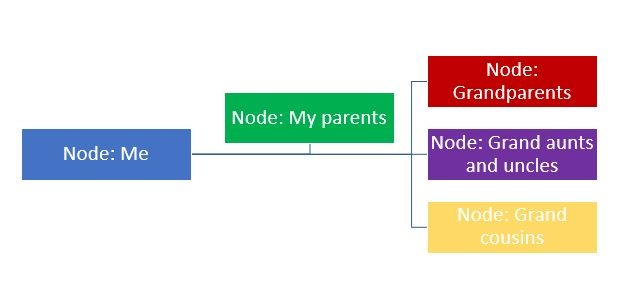

I started with the largest, most recognizable family history tool: Ancestry.com. Our library has a subscription, so Ancestry seemed like the logical place to start my training. And in order to engage productively with the database, I followed the genealogists’ rule of thumb, which Dr. Penelope Christensen reiterates in How do I prove it?: Always start with yourself and then work back in time, generational node by generational node (that is, from me, to my parents, to my grandparents, etc.).

To work backwards through generational nodes meant that my first step was to substantiate each life event with multiple document sources, oftentimes at least three. Starting with myself, I had to prove my name, place of birth and birthdate. Surely, as I live and breathe, I exist; however, proof must be acquired. My birth certificate is considered a valid primary source, and the newspaper announcement of my birth is a secondary source that corroborates the tale, and they both support the derivative oral source of the story I have been told of my origin on a tertiary level as well. Yes, I believe I have confirmed my name and my place and date of birth. Next level of generational nodes: My parents.

All I knew about my paternal ancestry was that we were German (I had known this fact since I was a kid because I recognized my surname as German). I began to research my father’s ancestors, like the strangers that they were, with two “simple” research questions: Where were they from actually? and When did they arrive in Canada? In addition to using Ancestry.com, I also used Family Search and several other genealogical tools to try to find the records that would help me to tell my story. All I knew about my paternal ancestry was that we were German.

My search revealed that one element of our family story was certain, documented and easier to prove: My father was born in 1949 in Minnesota. As my grandmother had originally told me, in January 1949, there was a wicked snowstorm in Emerson, Manitoba. The storm made it impossible for my grandfather to take my very pregnant grandmother to the nearest Manitoba hospital, so he drove her across the Canada-U.S. border to give birth. I could confirm this story because I was able to find my father’s American birth record.

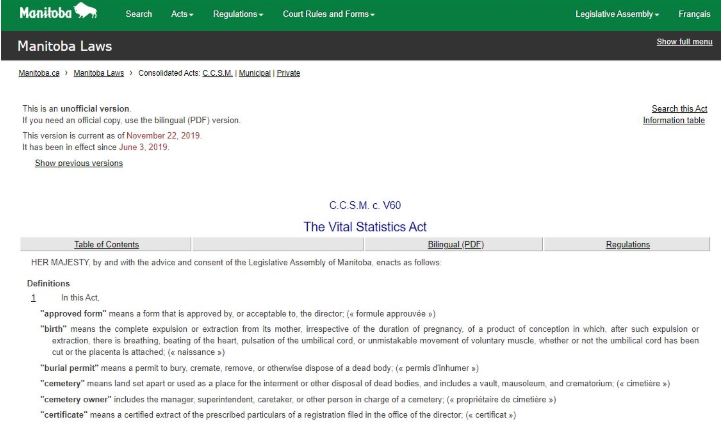

As a genealogy librarian, I was surprised that this record was so accessible, but I learned that the American privacy laws are much more relaxed than the Canadian laws. Had my dad been born in Manitoba, I would not have been able to find the record on Ancestry or on Family Search or even on the provincial Vital Statistics page because, as per the Vital Statistics Act, the birth event occurred less than 100 years ago.

Keen reader, you may have noticed that as a family history researcher, you must be attentive to time and place; i.e., you must become an expert on history and geography as well as on the relevant laws surrounding privacy and access to information.

Even with this expertise, knowledge of current genealogical methods and access to powerful digital tools, I have learned that I cannot always help patrons find the records that they need to trace their ancestry. Westernized, democratic societies tend to have the most available information, both online as well as in genealogical databases, but there are no formal international standards related to available data. Just because you can access a 1949 American birth certificate does not mean that you can access this data if the birth event occurred in Canada or in other countries such as the United Kingdom. And when I have patrons who require assistance to conduct Indigenous, Chinese, Jamaican or Eastern European family history research, the difficulties in proving the truth of their stories can pile up.

I find one of the challenges of my genealogical work is explaining to patrons why they face such inequities in accessing genealogical data. The digitization trend misleads patrons into believing that everything is freely available online. However, in my experience, genealogical research reflects systemic socio-cultural inequality. Imagine having to trace birth records from a country or a region in Eastern Europe, where records may no longer be accessible because:

- The area was bombed during World War II.

- The area had a fluctuating border over time.

- The documents were written in Cyrillic, not English.

- Records may be withheld under local privacy laws.

- The country that holds the records may not be open to the democratization of data.

Despite these challenges, however, I am now feeling more confident in my role as a genealogy librarian. I have not solved all the mysteries of my own family, nor am I always able to help patrons find the documents or the records they need to confirm their familial stories. But with a greater knowledge of genealogy “best practices” and access to good tools, I can at least help patrons start their search.

In Part II of this second installment, I will tell you more about finding my own roots.

Krista Woltman is the Local History & Genealogy Librarian for the Nepean Centrepointe branch of the Ottawa Public Library. She has been a Subject Matter Expert in Genealogy for three years, and has been a librarian for the Ottawa Public Library for over 11 years.

Feature photo by Evie S. on Unsplash