I used to feel frustrated when assisting patrons with their genealogical queries, partly because I lacked adequate training. But this subject can be mastered with formal and informal training.

Genealogy 101: Finding your roots to find your skill set

In this two-part second installment, I will share my own experience of learning, both formally and informally, how to become the genealogy specialist in my library.

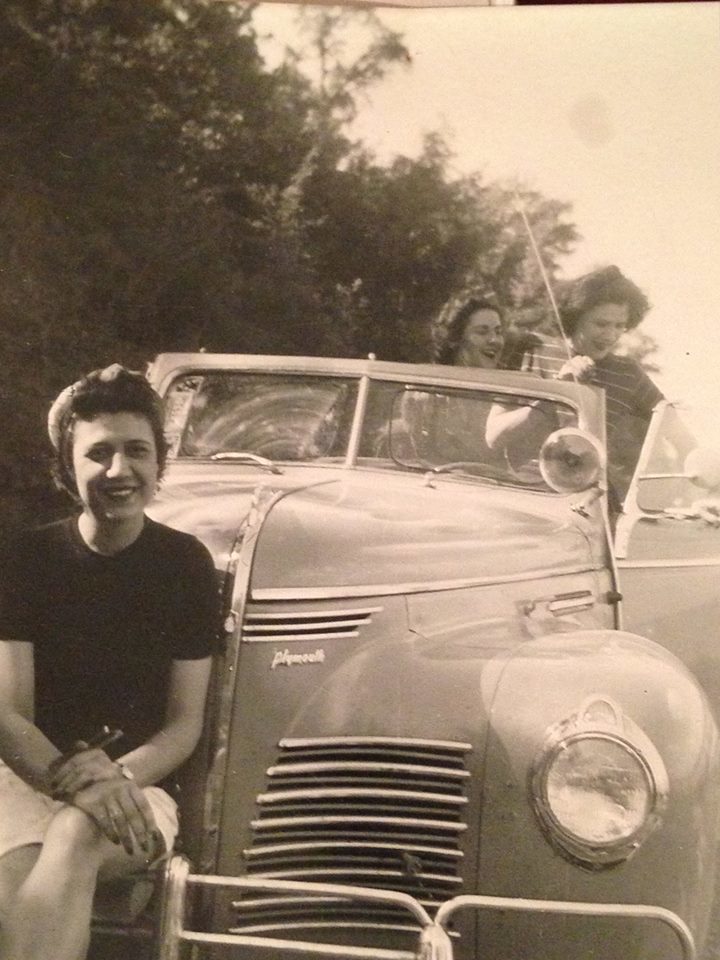

While helping others trace their ancestry has often been frustrating for me, providing this service has always made me feel a little bit wistful too. Having grown up not knowing much about my family culture, I envied patrons who had evidence that showed how long their families had been in Canada, when their ancestors had arrived, and where they had come from. Oh, and if they mentioned that they also had a family Bible, well, I would usually politely excuse myself to sob in the staff bathroom. Why? Because helping others discover their familial roots had exposed an issue in my own family that I realized I needed to address: Finding my own roots.

And I was terrified to look into my past! I did not know a lot about my roots, because my family did not share our stories or pass down our rich heritage and culture very much when I was growing up. But I also realized that, in my new role, I had a chance to get past these feelings, get to know my family history better, and become a genealogy expert. And in doing this personal research, I have definitely honed my genealogical skill set.

One grandmother, one birthdate and two weeks

As I can attest, it takes a very long time to become a “genealogy expert.” By default, I am the expert in my library because “expert” is my title and other staff look to me when a genealogy question comes in. And yet three years of experience does not an expert make.

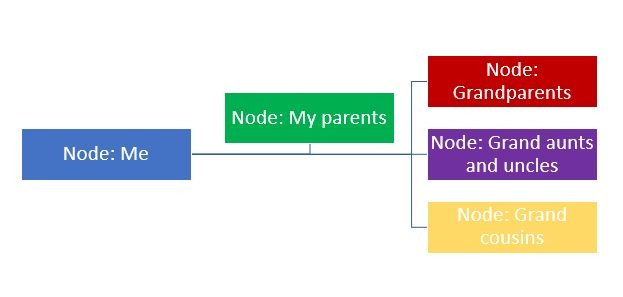

To improve my skills, I decided to study my own family. I started with a blank slate because I had no idea where my father’s ancestors had come from, or when they had arrived in Canada, so it was hard to define the scope of my research. However, I began with the second level of generational nodes: My parents.

As I mentioned in Part I, I found confirmation of my dad’s birth event, so up another node I went to my paternal grandparents. “I’m making quick work of this genealogy stuff,” I told myself.

I thought that finding my paternal grandmother’s birth event would be a cakewalk: My grandmother had been a woman in my life, so I knew her name, place of birth, date of birth and even the year of her death. Simple—this will take me no time! After all, I am an information professional. But even though I was an information professional, the process of confirming her birth event took time. In fact, I spent 14 days (two weeks!) confirming my father’s mother’s birth event. Part of the difficulty was that I had assumed that the name by which I knew her was her legal given name. Instead, I discovered that the name on my grandmother’s birth certificate was not the same name she had gone by her whole life. But in a beautiful wink from the universe, her birth name (Leonise) was the feminized version of my son’s name (Leo), a fact I had not known when I named my son eight years ago.

Of course, as a new genealogy librarian, my expectations of the research process were not necessarily realistic. I’ve learned that it is important to be patient with ourselves when we are conducting searches. We may try to go fast, in part because we expect the information that we want will all be online, but then we find that we have made mistakes and have missed our ancestors all together. Or even worse, we have identified the wrong relatives!

Given that oftentimes genealogy patrons can be older and new to technology, I’ve found that it is empowering for them to know that, as an information professional, I too have struggled with the process of finding the right information. I share the subtleties, along with the failures and triumphs, of my story quite a bit with patrons who attend the workshops, one-on-one research consultations, and Research Club sessions that I hold. My message is always “Be kind to yourself.” This shared experience and acknowledgement of our own expectations of the research process goes a long way to building relationships, I can tell you.

Using the census to track a family unit

One of my goals was to identify our homeland, and initially, it seemed that I would not be able to find this information. Clearly, my own story was not waiting patiently to be discovered, complete with sepia-toned photographs, names, dates, and places, with the narrator reading softly aloud, “Krista, here is your story.”

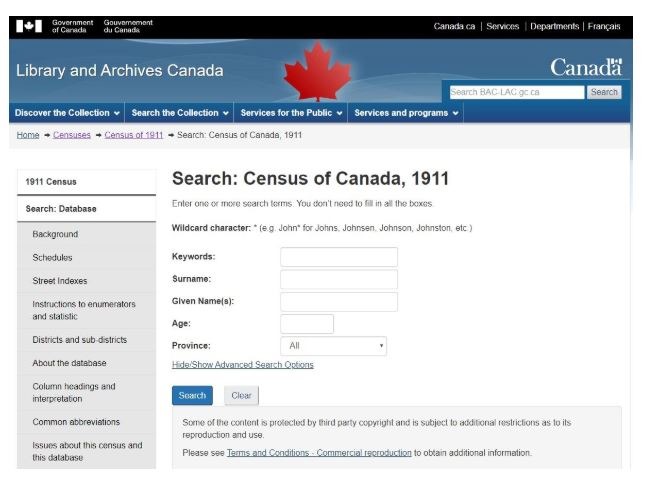

To try to move past this point, I studied the Canadian censuses because I knew that this was a good strategy when trying to locate family units. Potentially, I could acquire a lot of data relatively quickly, but I was aware that names change for a variety of reasons—the surname we have today may have experienced a journey or an evolution. So, overall, I knew that I would have to search all combinations of all the variant spellings of our given names and surname and that these imperative searches could take countless hours.

With what I knew about my grandparents, I decided to track one family unit, that of Willhelm Woltmann, and followed specific bread crumbs:

- I knew my paternal grandfather had been born in Manitoba in 1914, and this information guided me to search the 1911 Canadian census at the provincial level.

- Next, I browsed at the municipal level because my ancestors may have been living near the place of his birth event.

This strategy produced several results that were both positive and frustrating:

- I found a ghost that I just could not shake, even though his name was so far from what it should have been: Cristof Wourhan. Nonetheless, I printed the page from the 1891 census, plus the accompanying citation, and left him in my research file.

- I discovered a second man who kept coming up across the censuses. He fit the bill except that he did not seem to be the father of my direct relative, despite his numerous wives. I decided to prove that this second man was not my relative—this is a strategy I use—hoping to stumble upon my true ancestor. Every time I found the family unit of this second individual, its story changed just enough to make me question if his relatives were my family:

-

- In one census, they had spoken German and had claimed to have come over in 1907.

- But then in another, they had come from Poland, spoken Polish, and come over in 1899.

- And in a third census, they had been Russian, and they may have landed in 1903.

The government enumerator had included, crossed out and written over all these details, and, maddeningly, I have yet to confirm or explain any of them.

I continued to focus and obsess on the family unit of the ghost until, finally, I found the document that brought my ghost back to life. The head of the household that I had been tracking, Willhelm Woltmann, died in 1920, and his hand-scrawled signature, “Will,” was available on Ancestry. Once I could see his signature, I realized that the ligatures in his cursive “W” were identical to mine. Excited, I read through the document until I found the link to my ghost: “… gives everything to his brother Christof Woltmann …”!

Given that names are easily written down wrong, misheard or misunderstood and that even Ancestry’s indexing has glaring discrepancies, I now had the experience that genealogists lovingly refer to as “breaking through a brick wall.”

What’s next?: From historical research and storytelling to genetics

I did not expect such an adventure when I decided to start researching my family history. I thought that my task was relatively simple: To identify the year in which the original Woltmans had arrived in Canada and where they had come from. And I did accomplish this goal to some extent, and I definitely improved my research skills by using tools such as the Canadian censuses to track family units.

I also learned along the way that reconstructing a family history is never as simple as just finding a few facts. Having exhausted the available records, I am now asking myself, “Would having my DNA done make it easier and provide answers more quickly than the research I’ve done so far?”

DNA: Data for descendants, the third installment of this column, will look at this issue of tracing our roots through genetics. I have found that, once the genealogy patrons have used research, storytelling and relationships to find all the available records, they may decide to move into the world of DNA. And if they do, then everything can change.

Krista Woltman is the Local History & Genealogy Librarian for the Nepean Centrepointe branch of the Ottawa Public Library. She has been a Subject Matter Expert in Genealogy for three years, and has been a librarian for the Ottawa Public Library for over 11 years.