Learn about the benefits of constructing a multi-year internship from a MLIS student's perspective.

Finnish public libraries integrate diverse services to support equity & inclusion

As in North America, Finnish public libraries are mandated to provide equal access to materials and services for all citizens. Last year, I visited two libraries in southern Finland and learned that staff are pushing the boundaries of how access is defined: Books, new technologies and beanbag chairs share space with a host of needed community services, such as maternity health care. In widening the scope of service offerings, these libraries parallel efforts at the Thunder Bay and Toronto public libraries, among others, where inclusion and equity mean responding to a range of public needs.

Researching Scandinavian public libraries

Last May, I travelled to Scandinavia to investigate the role of public libraries in building community and fostering greater equity and inclusion. My trip was funded by a research internship from Carleton University, and I was particularly interested in the innovative practices employed by public libraries in Scandinavia. Through my travels to Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Finland, I hoped to identify best practices to share with the Ottawa Public Library’s board and administrators, who are in the midst of public consultations over a new central library space (Ottawa is my hometown). In Finland, I visited public libraries in two cities: Espoo and Helsinki. In both places, I found a range of programs that reflected an overarching commitment to ensuring equitable and inclusive access for all community members.

Espoo is located approximately 18 kilometres from the Finnish capital of Helsinki. These were two of the communities I visited during my tour of Scandinavian libraries last spring.

Espoo: Iso Omena Library

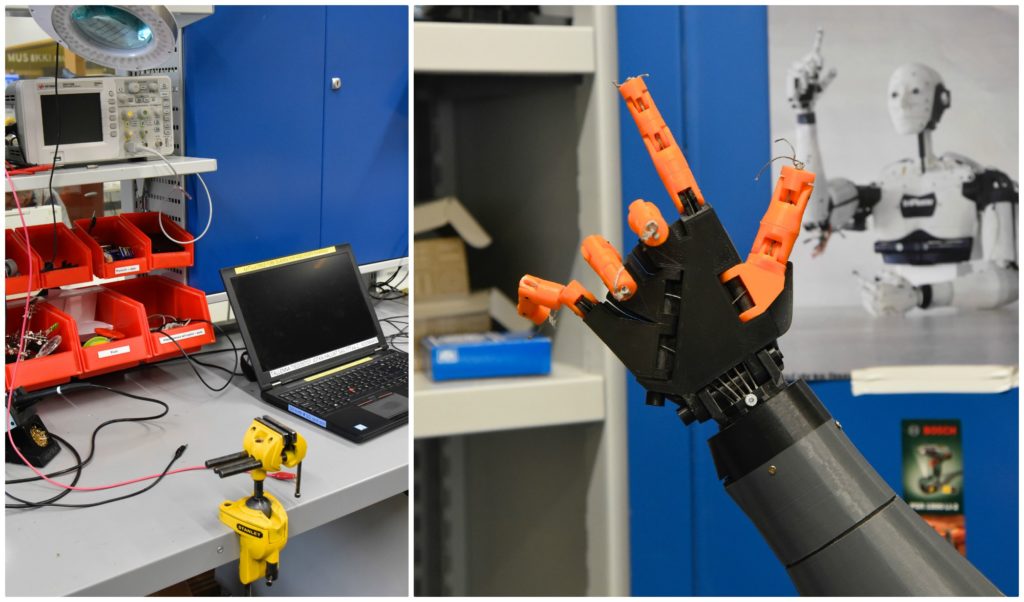

It’s 2 p.m. and the Iso Omena Library is bustling. Situated in Espoo, Finland, the library is located on the top floor of a shopping centre and feels like an extension of the mall—but with an anti-consumerism, for-the-people twist. One half of the library’s floor space is dedicated to children and youth, and it’s well used: Children practise electric piano, play video games, and read books to one another on large plush beanbag chairs. The teenagers have a dedicated hangout room, Vox, where they challenge each other to games of pool or chess, supervised and suported by trained youth workers. The library’s extensive makerspace takes up a separate room, where patrons are busy mending clothes or are creating mechanical parts using 3-D printers.

I toured Iso Omena Library with Oili Sivula, district manager of library services. The library’s layout and resources were incredibly impressive, but I was most intrigued by its unique “service centre” concept. According to Sivula, the service centre melds library space and resources with public services and is a “concept that makes it easier for Espoo residents to take care of their everyday matters.” These services include:

- A maternity and child health clinic

- A laboratory, providing examinations to patients who have a physician referral

- A medical-imaging centre

- A centre for youth services

- A mental health and substance abuse clinic

- A health centre

- A city-service point

- A helpdesk to secure Finnish social insurance

It’s a unique approach to public programming that, from what I witnessed, has proven to be incredibly successful and has made the drudgery of completing necessary everyday tasks a little more bearable for the community. Families accessing the maternity and child health clinic can wait for their appointment in the children’s library area and play with Lego blocks or run around a walled-in playpen. So too can those families accessing the medical-imaging and health care centres; instead of waiting in sterile offices, patrons can read and socialize in the vibrant library space.

Librarians are always nearby to provide public service assistance. They help patrons format resumes, look for a rental home or apply for Finnish social security. Iso Omena’s librarians guide in a way that is pedagogical; i.e., they are teaching patrons the necessary skills to access services on their own. Overall, the “service centre” model makes accessing critical bureaucratic services a little less taxing.

The city-service point is located near the adult library collection. A diverse set of patrons access myriad services—assistance in completing passport applications, obtaining fishing licences, and purchasing tickets to cultural events. The service point is an especially important resource for immigrants and refugees, who must apply for government documents with the added stress of not speaking Finnish. Iso Omena employs staff who speak Somali, Dari and Arabic and are able to assist patrons in accessing services and applying for documents. As Sivula and I walked through the service point, I overheard a young woman helping two non-Finnish speakers fill out a form. She guided them through each step and explained why the form had to be filled out a certain way. And the printing and scanning station was crowded with patrons printing out the necessary forms and documents for their applications.

By bringing civic services to an easy-to-access, commonly used space where librarians are available to answer questions, patrons can more readily apply for government documents, benefit from support services, and engage in public life.

Overall, integrating library and civic resources offers a people-first, community-oriented approach to libraries and librarianship. Sivula described the evolving role of librarianship as “people work first, content work second.” Discussing how libraries have changed over the past decade, she emphasized that Iso Omena’s service centre was designed to help everyone and, in particular, Espoo’s vulnerable populations. “Everything we do is for everyone. But we manage to keep up with those that need us [the most].”

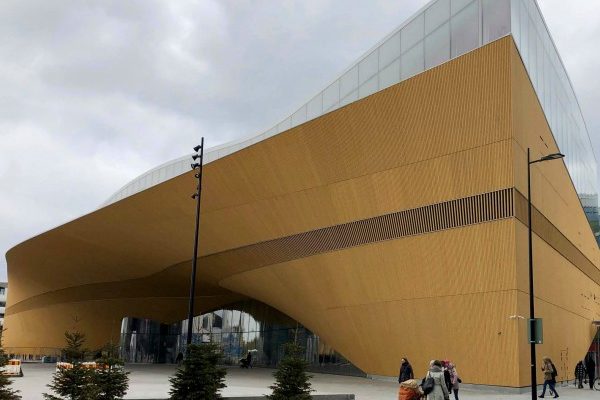

Helsinki: Library Oodi

Staff working at Library Oodi (seen in feature photo) in Helsinki, Finland, also design some of their programming to meet the needs of their most vulnerable community members; namely, immigrants and refugees, who are adjusting to Finnish life. For example, a specific space is rented to staff in the childhood and education sector so they can run “Play Park Story.” Play Park Story provides a place for stay-at-home parents to hang out while their children enjoy organized play. These play sessions are especially important for caretakers who have recently arrived in Finland and are often isolated from their parents and families. During a Play Park Story visit, library staff educate parents about library services and connect them to further resources, such as language cafés. Language cafés are hosted at many libraries across Finland and offer a judgement-free, fun and welcoming space for Finnish-as-a-second-language learners to practise Finnish with a Finnish-speaking staff member or volunteer.

Along with the Play Park Story space and the language cafés, an entire floor at Oodi is equipped for citizen activities, such as meetings or makerspace projects. All of the makerspace equipment (i.e., 3-D printers, sewing machines, video-editing workstations, music studios, etc.) and meeting rooms can be reserved free of charge, and patrons do not even need a library card to access them.

Katri Vänttinen, director of library services for the City of Helsinki, explained to me that, at their core, Finnish libraries set out to support the needs of vulnerable groups. Finland’s 2016 Public Libraries Act affirms that “municipal library services [are] intended for the use of all population groups,” and the first objective of the Act identifies the libraries’ commitment to “equal opportunities for everyone to access education and culture.”

Vänttinen stressed that “Finnish libraries are open for all, and they emphasize equality, freedom of speech, and lifelong learning.” Iso Omena Library and Library Oodi are exemplary in creating public spaces that meet the needs of immigrant and refugee populations, among others. For example, newcomers receive access to library services as soon as possible. “When [immigrants and refugees] arrive in Finland, they are then taken to the library, and given library cards, even if they don’t have their passports,” said Vänttinen. “Libraries are really part of the system that makes their entrance to Finland more humane.”

More than traditional repositories

In Finland, libraries are envisioned as places that are more than just repositories of books and audiovisual materials; they are also places of learning and personal development. Through concepts like Iso Omena’s service centre or Library Oodi’s play parks, Finnish libraries foster greater equity and inclusion—so critical in an increasingly diverse society. The exemplary practices I discovered in Iso Omena Library and Library Oodi offer inspiration to any library seeking to remain relevant in these times.

Photo credits: Samphe Ballamingie

Samphe Ballamingie is a senior undergraduate student at Carleton University, majoring in Sociology and minoring in Environmental Studies. Her research interests lie in the public realm, and include social justice issues, urban design and visual methodologies.