The thinking of Comrade F. Dobler from the early 20th century remains relevant and even prescient: those who need open access to information may be those who are fundamentally excluded from public libraries.

Unlevel playing field

Open for all? offers a “think piece“ rather than an intellectual analysis. Columnist John Pateman shares his personal observations on issues and his columns are designed to promote discussion and professional debate. He has arrived at his conclusions after 40 years working in public libraries of/in all types and locations.

Riffing off the theme of my last column (Race matters), I would like to explore how white middle class professional library values can create an unlevel playing field for Indigenous organizations and individuals. How? By privileging one world view over another.

I was recently invited to take part in the National Heritage Digitization Strategy. The first thing I noted was that there were relatively few applications from Indigenous organizations. Maybe potential Indigenous applicants looked at the Project Assessment Criteria (PAC), realized that the odds were stacked against them and didn’t bother to apply. After all, it takes a lot of capacity (time and money) to apply for funding, and it makes sense to focus organizational efforts on those applications that are most likely to succeed.

When I saw that the PAC might be a barrier to access to Indigenous applicants, I raised this observation as a concern to other committee members and was assured that this barrier would be taken into account during the selection process. At the end of this process, my concerns were confirmed as very few Indigenous organizations had made the final cut. There was one PAC in particular that proved more challenging for Indigenous applicants to achieve: Collaboration.

The collaborative PAC was defined as “projects that use partnerships to maximize efficiency and knowledge sharing and to leverage existing infrastructure.” The fact is that Indigenous organizations find collaborative work more challenging than white organizations do. This difficulty is not because Indigenous organizations do not want to form a partnership; in my experience, they would really like to do so, and this collaboration is very much a part of an Indigenous world view of inclusion and a “we are all in this together” perspective. The problem is that white (or “corporate”) Canada does not want to form partnerships with Indigenous organizations.

Research carried out by Indigenous Works—Researching Indigenous partnerships (2017)—found that the majority of “corporate” (white) Canada lacks “the motivation, competencies and organizational readiness to effectively engage and partner” with Indigenous organizations. One third of corporate Canada never considered engaging, and the reasons given for this lack of engagement included “‘passive approach, limited perceived value, time/money, and allocate few resources.”

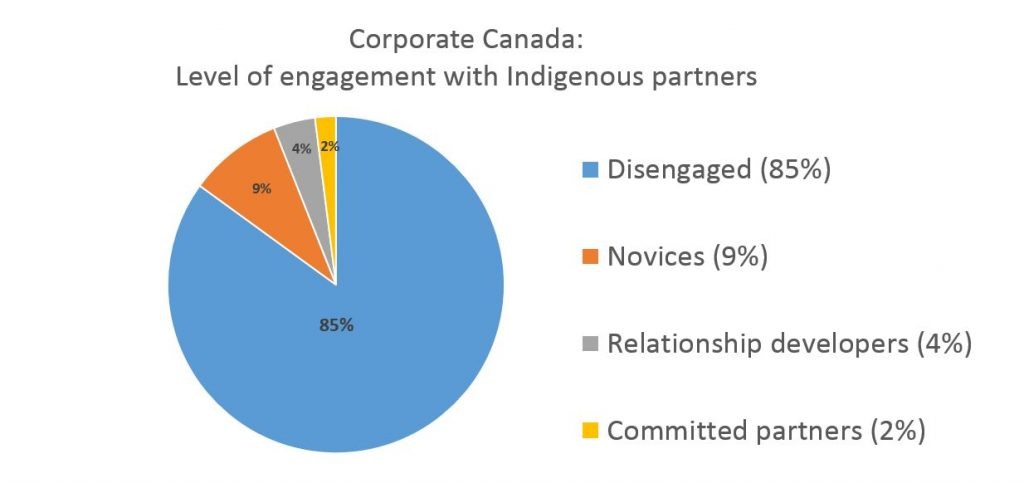

The chart below visualizes corporate Canada’s engagement with Indigenous partners. Nearly 70 percent of the organizations said that to move forward they needed guidance from Indigenous groups, dedicated, experienced resources, and mentorship from other businesses.

Given that 85 percent of corporate Canada is disengaged and that only two percent is committed partners, it is not surprising that Indigenous organizations find it challenging to tick the collaborative PAC box. I am not targeting a particular program or institution here, because I think that what I describe is endemic in the corporate sector; i.e., a systemic problem. These systems (in this case, the PAC) are designed by and make perfect sense to white middle class professionals because these systems are a reflection of white values and world views. The honest intention is to design systems that are objective, inclusive, fair and open to all. But, as I have demonstrated with the PAC, the outcome is very often the opposite—the impact is culturally specific and tends to exclude.

To fix this problem, Indigenous organizations could engage in the design of systems, which should reflect both white and Indigenous world views. Better still, Indigenous people should be part of the organizations that design these systems. This inclusion means recruiting Indigenous people at every level of the organization—and not just at the lowest level. It means recruiting Indigenous chief librarians and directors, as well as technicians and assistants. And it particularly means hiring more Indigenous librarians. The barriers to this inclusion are also systemic. Many librarian positions require a graduate degree (e.g., a Master of Library and Information Science or a Master of Library and Information Studies [both MLIS]), a condition which is a huge challenge to prospective Indigenous applicants, for whom the whole higher education system is not a level playing field.

Employers and unions must work together to open the public library doors to an Indigenous job applicant. They must put as much, if not more, focus on lived experience as they do on educational qualifications. After all, what is more important: walking in the shoes and seeing through the eyes of an Indigenous person, or having an MLIS certificate? No amount of education and training can replace real lived experience when identifying, prioritizing and meeting the needs of Indigenous communities.

The Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) is leading the way in public libraries. CUPE’s membership survey—Employment equity: A workplace that reflects the community (2014)—shows that women and racialized CUPE members are more likely to be precariously employed than other members. This survey also shows that, relative to the national population, the percentage of racialized or Indigenous CUPE members is less than the national average. Fifteen percent of CUPE members are racialized, less than the national average of 19 percent, and 3.4 percent of members are Indigenous, less than the national average of 4.3 percent.

As the CUPE report points out, “Employers have a responsibility to ensure that workplaces are inclusive and free from discrimination. However, inequalities often exist as a result of years of hiring practices that have excluded certain groups, usually unintentionally. For example, an employer may require unnecessary educational qualifications for certain jobs which act as a barrier for people who have difficulty accessing higher education.”

We need to ensure that our workplaces are open to everyone in our communities, including groups that have historically been marginalized in the labour market.

John Pateman is the CEO of the Thunder Bay Public Library. He contributes to the library field through work on groups such as the CFLA-FCBA Indigenous Matters Committee.