I am intrigued with the work of fabulous secondary teacher librarian, Jonelle St. Aubyn. Her practice is both familiar and innovative.

An authentic narrative around Canada’s history

Now that #Canada150 has all but disappeared from social media and nightly newscasts, schools must remain vigilant in our work to embed an authentic narrative around Canada’s history and the ongoing systemic oppression and persecution of First Nation, Métis and Inuit peoples. It would be all too easy to fall back into our own obliviousness of both the historical and present day truth of Canada’s first 150 years.

About this time last year I made a conscious choice to re-educate myself about Canada’s long ignored history of cultural genocide against First Nation, Métis and Inuit peoples. I began by connecting with a group of interested students, the Coordinator of First Nation, Métis and Inuit Education for our board and reading, reading, reading!

My first read was Indigenous Nationhood: Empowering Grassroots Citizens by Pamela Palmater.

The experience of reading the blog posts gathered in the book was just that—an experience. I was immediately emotionally connected to the text. I was felt angry and sad and embarrassed and most of all ignorant! To that end, I wrote my own post at the time: “Owning my ignorance.”

Since then, I have found myself keenly aware of the importance of this conversation, on Twitter and Facebook, at baseball games, on newscasts, in school hallways, staff dialogue, classrooms, during the morning announcements and most of all in the school library learning commons. I have continued to read, reflect, engage and ask questions. I am so incredibly far from being an expert on this topic that I would say I am just scratching the surface. But I can say that I am conscious and I am aware. My ongoing reading list thus far (too many to list) has reflected this desire to deepen my own understanding.

Currently I am reading The Comeback by John Ralston Saul.

The quote below has stuck with me:

“We must reinstall a national narrative built upon the centrality of the Aboriginal peoples’ past, present and future. And the policies of the country must reflect that centrality, both conceptually and financially.”

School libraries revolve around narrative. Sharing of long-told fairy tales and fables, the inspiring images of adventure found in graphic novels, the seemingly effortless settings described in the fantastical worlds of magical tales and the popular early novels that transition the learner to independent reading are at the heart of every thriving elementary school library.

But another type of narrative exists, and that is the narrative of our own history. Non-fiction texts are, I could argue, a form of narrative full of powerful information shared through the lens/bias of the author, editor, publisher and more. In my current practice no narrative is more essential to our future as a country than telling the honest, painful truth about how Canada came to be and how that legacy continues to impact the daily lives of children, youth and adults who are members of First Nation, Métis and Inuit communities.

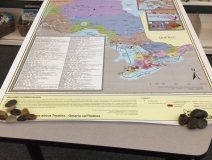

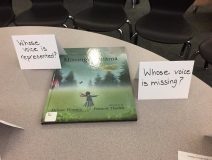

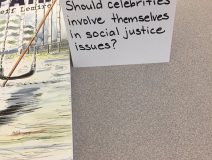

To that end members of our staff introduced a staff-wide inquiry opportunity into embedding this narrative in our daily practice. Here are some images of the meeting design, resources and prompts we used to begin the conversation.

The school library learning commons has the power to change the narrative. We must use that power to move the dialogue forward with staff, to engage our communities and to inspire our students to become a generation of leaders who will learn from the truth of first Canada’s first 150 years as a country and make sure that we do much, much better. The individual stories and lived experiences of First Nation, Métis and Inuit peoples are not ours to tell but, their voices must come to the centre of our collections, conversations and collective consciousness.

Let’s ask ourselves:

How can school libraries change the narrative beyond #Canada150 and work authentically towards meaningful truth and reconciliation for generations to come?

Jennifer Brown is the Teacher Librarian at the Castle Oaks Public School in the Peel District School Board. It’s Elementary: Thoughts About School Libraries is a regular column on Open Shelf. Jenn can be reached at jennifer.m.brown [at] peelsb.com and by following her Twitter account@JennMacBrown.