Learn about the benefits of constructing a multi-year internship from a MLIS student's perspective.

Net neutrality: Is the end in sight?

On December 14, 2017, the U.S. telecommunications regulator, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), voted to repeal the country’s net neutrality regulations.

What are the implications of this decision—not just for American citizens, but also for Canadians? And what about libraries? If the internet has become the de facto public library for many people across the continent, will access to information change and, as result, the services we offer?

We asked Michael B. McNally and Katy Anderson to share their thinking on this issue as both are keen followers of internet-related issues—here’s your net neutrality primer!

Katy is an digital rights advocate at OpenMedia, an organization that works to keep the internet open, affordable, and surveillance-free. Michael is an assistant professor at the School of Library and Information Studies at the University of Alberta and his research interests include intellectual property and its alternatives, open educational resources, rural broadband policy and government information policy.

Both recognize that the recent FCC ruling threatens the principle that all data “should be treated as equal” and that Canadian regulations provide a good measure of protection. But the impact on libraries? Well, on that issue they differ.

What is net neutrality and why does it matter?

Michael

Net neutrality is a concept first articulated by Tim Wu in 2003 and is often defined as the idea that all data (or more specifically packets) should be treated equally and that network providers should not privilege any type of content. In the Canadian context, net neutrality has been applied in three areas:

- internet service providers (ISPs) should not block access to certain sites (which one ISP did in 2005);

- ISPs, particularly mobile ISPs, not privilege their own content over others by not counting it against data caps (the “zero-rating” debate which the CRTC ruled on last year);

- content providers not be able to pay to have their content travel faster than competitors.

While not specifically defined in Canadian law, sections 27(2) and 36 of the Telecommunications Act do provide protection against unjust discrimination, undue preference and interference with the content in telecommunication services.

Katy

I think of net neutrality as the underlying principle that all content on the web be treated equally and the idea of three pillars works for me too, particularly in terms of consumer protection.

- No blocking: Internet Service Providers (ISP), like Bell or Telus, can’t restrict access to websites they don’t like or might be direct competitors.

- No paid prioritization: An ISP can’t charge a content provider, like your favourite news site, more to access readers or block them entirely if they don’t pay a fee.

- No throttling: An ISP can’t slow down traffic from a website that doesn’t pay a fee. A classic example is when Comcast slowed down Netflix and demanded they pay a large fee to have their streaming content delivered without a slowdown to viewers like you and me.

Strong neutrality protections in both Canada (we call it “common carriage”) and the U.S. have fueled the incredible innovation we’ve seen online over the last two-and-a-half decades. Because all content is treated equally, it’s created an atmosphere where ideas and services can be created on their merit, rather than because they’ve become entrenched.

What are the similarities/differences between Canadian and U.S. net neutrality regulations?

Michael

There are significant historical differences in the way telecommunications and broadband are regulated in both countries. However, the central and recent issue with respect to the treatment of net neutrality in the U.S. is the Federal Communication Commission’s (FCC) decision to re-classify broadband as an information service.

Prior to 2015, the FCC considered broadband an information service and therefore it was exempt from the common carriage regulations in the Communications Act of 1934 and Telecommunications Act of 1996. In 2015, the FCC re-classified broadband as a telecommunication service, bringing it under the common carriage provisions effectively creating net neutrality in the U.S. But the re-classification back to an information service in late 2017 neuters net neutrality in the U.S.

In contrast Canada doesn’t have net neutrality enshrined in law, but the relevant sections of the Telecommunications Act do provide a much stronger degree of net neutrality than in the U.S.

Katy

Ditto—I also think we’ve got a relatively strong legal “safety net” in Canada.

As Michael points out, the protections against unjust discrimination outlined in Section 27 of Canada’s Telecommunications Act are important. I also see the 2016 decision by our internet regulator, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC), to place restrictions on telecoms around “zero-rating” practices, as critical to keeping the net neutral.

Zero-rating means that an ISP treats some data as unlimited and doesn’t count it against a customer’s data cap. When ISPs do zero-rate data it can create an unequal playing field where there is an incentive for a person to use some data (or content) over others so that they stay under their data cap and are not charged extra fees.

These protections are critical. In Canada, many of our ISPs are both content carriers and producers so they not only own and control the pipes that transport our data, they also own the data itself. This is a double whammy for consumers.

For example, Bell Canada owns CTV or TSN while Rogers owns Rogers Sportsnet and magazines like Macleans. In these cases, it is advantageous for Bell to zero-rate CTV content, so that a viewer is incentivized to watch CTV over, say, CBC or Global. The CRTC ruling against zero-rating was heralded by open internet proponents across the world as a way to strengthen net neutrality.

With the FCC ruling in late 2017, the latest battle for the web might well have begun. The country’s own hard-fought net neutrality protections, the Open Internet Order of 2015, have been repealed and we’re waiting to see if members of Congress will ratify the repeal or order the protections be reinstated.

What are the implications of net neutrality for libraries?

Katy

For me, with net neutrality protections in place the internet is kind of like a giant library, where access to information is only limited by an individual’s ability to consume it.

With either a public library card or an internet subscription, an individual can access everything both “portals” have to offer. This open access approach is quite different from a cable TV model, where information is divided into packages and citizens have to decide what they want to, and can afford to, pay for.

With the repeal of American net neutrality protections, I think it’s very likely that libraries will be limited in the services they can provide to their patrons. ISPs could charge libraries more to deliver content, like videos or free access to large databases. Greater restrictions could also impact innovation in libraries. How do you come up with innovative ways to deliver content if you’re forced to compete on an unequal playing field where entrenched corporations are given the upperhand in terms of accessing citizens because they have more resources to offer ISPs?

Michael

Net neutrality does ensure that the ISPs for libraries are not privileging or impeding certain types of content. More broadly, it is possible to conceive of net neutrality as an extension of intellectual freedom.However, it is important to recognize that net neutrality does have some practical implications and, in the end, I think that the most important impacts of net neutrality are on ISPs, not libraries.

Other thoughts?

Katy

With the rollback in American protections, we have to recognize that strong net neutrality protections are always under threat.

Threats come in the form of proposals, like the recent Bell-led coalition “FairPlay,” which is asking the CRTC to investigate creating a body that would create a blacklist of websites suspected of hosting pirated content. This overreaching proposal could see net neutrality eroded by attacking the idea of “no blocking.”

Many internet advocates have voiced opposition towards the proposal, including Canadian internet scholar Michael Geist, who called it a “disproportionate, unconstitutional proposal sorely lacking in due process that is inconsistent with the current communications law framework.”

If we think that an open internet is important to our society, then we must voice our opinions to the CRTC, so our regulator is empowered to make good decisions on our behalf. OpenMedia’s Stop Canada Censorship is one tool for voicing your opinion to the CRTC.

Michael

We have to remember that, even in Canada, there are already limits on net neutrality that we think are practical or desirable. For example:

- Many Canadian ISPs participate in the Cleanfeed program which blocks access to sites known to distribute child pornography.

- ISPs block certain types of traffic (such as denial of service attacks).

And certain types of packets, such as those carrying voice data, are more sensitive to delay than other kinds of packets, and as such it is important there be protocols that privilege certain types of packets over others. However, net neutrality should ensure we don’t have discrimination among packets of the same type.

Lastly, the Canadian government has recently and repeatedly committed to enshrining net neutrality in Canadian law as part of the review of the Broadcasting and Telecommunications Acts. So, as Katy points out, interested groups and individuals should make their voices heard in the review process.

For more on net neutrality, including a thorough discussion of Canadian history and treatment, see the recent webinar by Canadian net neutrality scholar and activist Ben Klass. Tim Wu’s original article is: Wu, Tim. 2003. “Network Neutrality, Broadband Discrimination.” Journal of Telecommunications and High Technology Law, 2: 141-176.

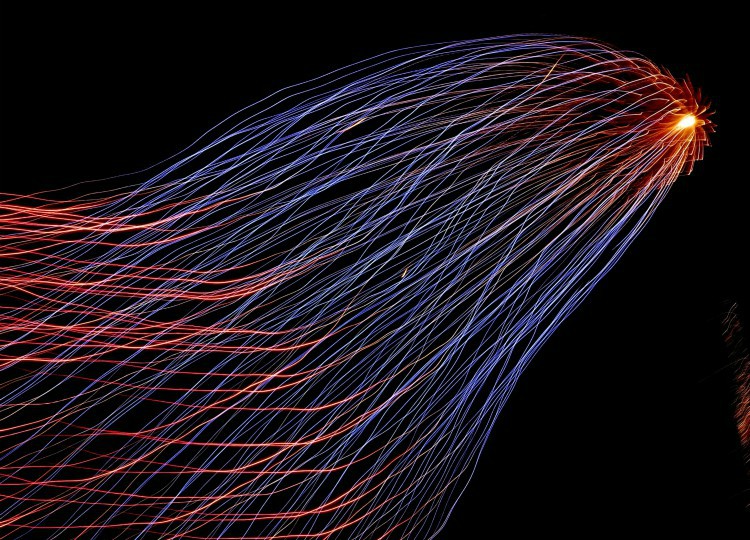

Photo credit (feature and slider image): Rawpixel on Unsplash

Photo credit: Hunter Harritt on Unsplash

Katy Anderson is an digital rights advocate at OpenMedia, an organization that works to keep the internet open, affordable, and surveillance-free. OpenMedia creates community-driven campaigns to engage, educate, and empower people to safeguard the Internet. Katy’s work at OpenMedia focuses on working towards universal access to fast, open and affordable networks. Before joining OpenMedia, Katy worked as an online journalist at the CBC and Postmedia specializing in online platforms.

Michael B. McNally is an assistant professor at the School of Library and Information Studies at the University of Alberta and his research interests include intellectual property and its alternatives, open educational resources, rural broadband policy and government information policy. He is a Research Fellow of the Van Horne Institute and has participated in policy consultations held through the House of Commons, Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission and Innovation, Science and Economic Development. Michael has a PhD and MLIS from the University of Western Ontario.

This Post Has One Comment

Comments are closed.

Hi Katy and Michael, great article! I followed the FCC vote very closely and like many, was very disappointed with their choice to repeal. There seemed to be major public outcry about the repeal of the Open Internet Order of 2015 yet the FCC went ahead and voted 3-2 to remove it. Is there any accountability from the CRTC to “listen” to our voices or could the results be much the same? With Ian Scott being a former telecom executive (Telus and Telesat if I’m not mistaken) do you think the CRTC results will be much different? or do we expect the CRTC to side with the telecom industry regardless of public support against the Bell-led coalition “FairPlay”?

Thank you for looking at Net Neutrality through the lens of Canadian librarianship and for sharing the link to the Stop Canadian Censorship form!