Miranda Hill is changing Canada's literary landscape .... quite literally. As Executive Director of Project…

Dan Cohen, Executive Director, Digital Public Library of America

Jennifer Dekker: Hi Dan, thanks for taking the time to talk with me. How did you come to be the Executive Director of the Digital Public Library of America?

Dan Cohen: It’s great to talk to you. I am a classically trained historian – I received a doctoral degree in Victorian History and the History of Ideas. I did my dissertation in the analogue way, doing in-person work at archives, and studied how pure mathematics was considered a divine language in the Victorian age; that dissertation became a book called Equations from God. Even though I received standard history training, I was always interested in computers and how they might be applied to historical topics.

Soon after completing my PhD, I met Roy Rosenzweig. Roy had started the Center for History and New Media (CHNM) in 1994 at George Mason University. I joined at the beginning of 2001 as an Associate Director of a digital history of science program. I was excited by Roy’s work in digital history (which he called, pre-“digital,” ‘new media’) and that I was able to combine my historical training with my interests in the digital realm.

CHNM grew rapidly – we went from three staff in 2001 to 60 in 2013 by the time I left. We pioneered projects likes Zotero, an open source citation management tool and Omeka, an open source platform for digital exhibits. I eventually became Director of Research Projects which allowed me to create things that would help historians, librarians and others to further digital scholarship. For example, we developed some important early digital collections such as the September 11 Digital Archive – it was one of the very first born-digital collections and was the Library of Congress’s first born-digital acquisition.

As I mentioned, CHNM grew rapidly in the decade I was there, but tragically Roy died in 2007 of cancer at age 57 and I succeeded him as the overall director of the center from 2007 to 2013. That was strong preparatory work for becoming director of DPLA because the projects I’d been involved in at CHNM were very DPLA-ish. Roy had always had a strong ethic of open and democratic access to information, especially to historical materials. I joined the DPLA working group in 2011 and in March 2013, I left CHNM and my professorship at George Mason University to serve as the founding Executive Director of DPLA.

Jennifer: Why is the DPLA project important?

Dan: The DPLA is an important attempt by institutions to democratize access to our cultural heritage – it has patrons’ interests at heart. We are a combination of America’s libraries, archives and museums – and we help everyone globally have access to the content of America’s collections. Unlike a large entity like Google, we are only answerable to the public and serve the public’s need for access to our shared culture.

Jennifer: Are you in competition with Google?

Dan: I get asked that question often. The short answer is that we have a very different mission. DPLA is a non-profit entity, and our collection is much broader than, say, what Google offers with Google Books. Like its name suggests, Google Books contains only digitized books, whereas DPLA includes many other formats such as images, text, moving images, physical objects and audio recordings. Critically, we also include small historical collections as well as large ones, whereas Google has tended to focus on major museum and library collections.

DPLA plays an important and complementary role to Google’s efforts – we have no ill will toward Google. We are both part of a multi-faceted effort to democratize access to cultural heritage, although I do think it’s important that DPLA exists as a non-commercial balance to what Google is doing.

Jennifer: You probably knew I would have to ask the next question: what about Canadian content in DPLA?

Dan: DPLA includes content in 500 languages and contains materials from many countries, including Canada, but we have had to set some boundaries for collecting. As it is, the DPLA is already expansive but we have not become imperialists – we are not scurrying over the border to get material from Canada. We are however interested in collaborating with other regions, and one of our most established partnerships is with Europeana. We have collaborated with Europeana on various exhibits such as Leaving Europe: A new life in America.

Further, I have regular calls with directors of national digital libraries from around the world. We share ideas, methods, technologies. In fact, I just spoke with someone from India who is thinking about starting an initiative similar to the DPLA and there could be another project in East Asia. Projects like the DPLA are non-trivial to set up – they take years of planning and considerable funding. We are so appreciative of Europeana’s huge contributions to DPLA, and envious of how much progress they have made, but we try to remember that they’ve existed for six or seven years and DPLA has only been around for less than half that time.

It’s always the case that the grass is greener. I suspect that Canada has digital assets in place and that a similar project could be realized. Remember too that the DPLA is completely open source: all of our tools are on Github, so it could happen in Canada just as we used Europeana’s model for the DPLA.

Jennifer: How can librarians and library staff in Ontario and Canada promote the DPLA?

Dan: First of all, thank you! It’s such a young project and we are just starting to become known. We’d love people in Ontario and Canada to promote it. The web is very large – people don’t instantly find DPLA simply because it exists: basic dissemination is important, and it’s a great help to let library users understand that the DPLA offers a very wide range of materials from around the globe, so adding DPLA to online finding guides would help.

You have a savvy audience and there are other pieces that I suspect would be attractive to them, such as our unusual browsing mechanisms: DPLA allows browsing by map, by latitude and longitude – even Google doesn’t offer this feature – by timeline or by curated collection: people often start with the online exhibits; they are among the top hits on the site.

There are other things that librarians can tease out too. We recently started, thanks to funding from the Whiting Foundation, rolling out the DPLA in educational settings such as K-12 schools, community colleges, small liberal arts colleges, and research universities. We want to enlist all sorts of librarians from around the world to identify primary source sets on particular topics such as history, politics, music, the visual arts, and the sciences.

In fact, there is a lot of room to participate in the DPLA. We have a Community Reps program and it would be great to have some more people from Canada involved with that. Librarians or others who are interested can apply to get a formal designation as a Community Rep for one or two years and they help to evangelize the DPLA – they do presentations, set up hackathons and that sort of thing. If you go to the DPLA site, there is information in the Get Involved tab.

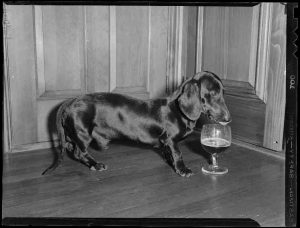

Jennifer: I read that your favourite document in the DPLA is this photograph of a dachshund drinking what looks to be a glass of beer. Why is that your favourite document?

Dan: Your readers won’t know this, but during this interview I let out and in my two long-haired miniature dachshunds – there are a dozen or so pets that are part of the DPLA family and they are important parts of our work! When we have Skype check-ins we often have dogs barking in the background.

This document is an example of the sheer breadth of heritage of the DPLA. We have thousands of photographs of dogs and cats – the DPLA offers an accessible record of regular American life; we are not only democratic in our delivery of information, the record itself is also democratic. It reminds me of Roy’s vision for democratizing the historical record, and DPLA is the most expansive and accessible way to offer that.

Jennifer Dekker is a Subject Specialist Librarian at the University of Ottawa serving the Faculty of Arts. She can be reached at jdekker [at] uottawa.ca.