Learn about the benefits of constructing a multi-year internship from a MLIS student's perspective.

Makerspaces: Service or learning resource?

At the 2017 Computers in Libraries conference, a librarian asked “Do you use your 3D printer, as a service or resource?” This seemed like a strange question to me at the time, but not now. I realize now that the distinction between service and resource—like Open Shelf columnist Jennifer Brown’s distinction between product and process—fundamentally shapes my understanding of makerspaces as digital literacy learning spaces or resources.

Service or resource?

School librarian Jennifer Brown writes the Open Shelf column It’s Elementary: Thoughts on school libraries column. In her April 2017 article, “Uncovering the “truth” about makerspace,” she shared her initial doubts about adding a makerspace to the learning commons at her school. “I questioned if the mere use of the word “maker” implied a value of product over process.”

This is an astute distinction, as it is tempting for library staff to define a makerspace in terms of what patrons might produce within the space. And, if the space is envisioned as a place for production, then we are providing a service because such services offer technology and staff time to facilitate physical outcomes, such as an engineer’s prototype, a hip hop single for demo, a sign for a small business.

However, if we see the makerspace as a learning space—a place where patrons come to learn a new skill, for example—then we are really creating a learning environment or resource for our patrons. As a resource, the makerspace offers technology and staff time as a learning tool and the physical outcome is secondary to a learning outcome. A bracelet printed in a makerspace may be a more valuable outcome then the prototype from an engineer, if learning to create the object is necessary.

And, in an age where increasingly digital literacies are privileged and required in a range of contexts (school, work, volunteer organizations), there is a compelling argument to be made for seeing these spaces as a resource rather than a service.

Makerspace as digital literacy resource

Makerspace technology is fundamentally technology that supports the acquisition of digital literacies, which are in fact a combination of interrelated literacies.

Heidi Julien`s definition of digital literacy as “the skill set needed to access, evaluate, use and create digital information” is expressed more completely in MediaSmart’s “What is digital literacy” model. This framework suggests that access, use, understanding and creation form a progression to more transformative individual and social learning outcomes.

Within the context of a makerspace, digital literacy starts in the mind: with an idea for a tool, a song, a sign—anything that can be imagined and then created through human effort into an independent and real object or work.

In libraries, we are seeing this potential or “affordance” of makerspace technologies already being realized. The Chicago Public Library reports in Making to learn (2015), that digital literacy was the single greatest impact measured after the launch of their Maker Lab in 2013. Close to 90 percent of survey respondents agreed that, after attending a Maker Lab program, they would read or learn more about the topic or tools they experienced.

At Newmarket Public Library, the Maker Hub (our makerspace) began as a digital literacy initiative unintentionally. The Ontario Libraries Capacity Fund allowed us to purchase a 3D printer, a vinyl cutter and an IMac, long before we had a dedicated space in which to house this equipment.

(Left) Welcome to the Newmarket Public Library Maker Hub. (Right) The one-time storage closet has developed into a workable space with a variety of technology including an iMac digital media station and three 3D printers.

(Left) Welcome to the Newmarket Public Library Maker Hub. (Right) The one-time storage closet has developed into a workable space with a variety of technology including an iMac digital media station and three 3D printers.

Programming then became the way the public first accessed the technology. We offered a bi-weekly certification class and monthly programs for the vinyl cutter and the 3D printer.

The Maker Hub eventually acquired a distinct identity within our library community. A repurposed storage room has bloomed into a public area that has its own staffed hours. We have added some additional technology, and branded the space with a logo. However, two new questions about the space have since arisen:

- Why are patrons not coming back to use the technology after taking a class?

- What is the best assessment of the space’s usefulness?

- The amount of cost recovery revenue generated? Much of the revenue came through promotional items printed by staff or by users already familiar with the technology who seldom took a class we offered.

- A learning outcome metric—quantitative measures like instruction sessions attended, variety of topics and classes offered, and qualitative measures such as application of a new skill or ability.

In asking these questions, we have been confronted by the issue of service vs resource. Is the Maker Hub just a physical space with available technology (i.e., a service to our community) or is the space a learning place, where the technology serves as a teaching resource?

Makerspace access and use policies

So, if we envision our makerspaces as digital literacy resources, then our public access and use policies for the technology within the space must reflect this thinking.

For example, if the makerspace is a service, we could assume that skilled patrons will be using the technology and therefore only need to sign a legal waiver. However, if the makerspace is a resource, then we could assume we need to train our staff to offer instruction to patrons.

Of course, the lines between service and resource could blur. Maybe the engineer with a prototype cannot afford to buy a 3D printer herself, or pay a service bureau to print it; the library may be her only path to getting her invention to market? Plus, as so many librarians (public, school and academic) already know, the development of these policies is often dependent on factors beyond their control: staff availability, training and programming resources, as well as available physical space.

Nonetheless, policies and procedures should reflect a basic commitment to the makerspace in a given library as predominantly either a service or a resource. Having a makerspace charter can help us clarify which applies in the context of our own libraries.

At the Newmarket Public Library, we don’t have policies relating to the Maker Hub, although we have a Maker Hub agreement, which is a legal waiver to use the technology that patrons sign during the certification class.

Any official library policy has to be approved by our Library Board, so starting with a makerspace charter could be a simpler, less official way to influence policy and may ultimately result in creating one, or amending an existing policy, for example our Public Computer Access and Use Policy to include a section on the makerspace.

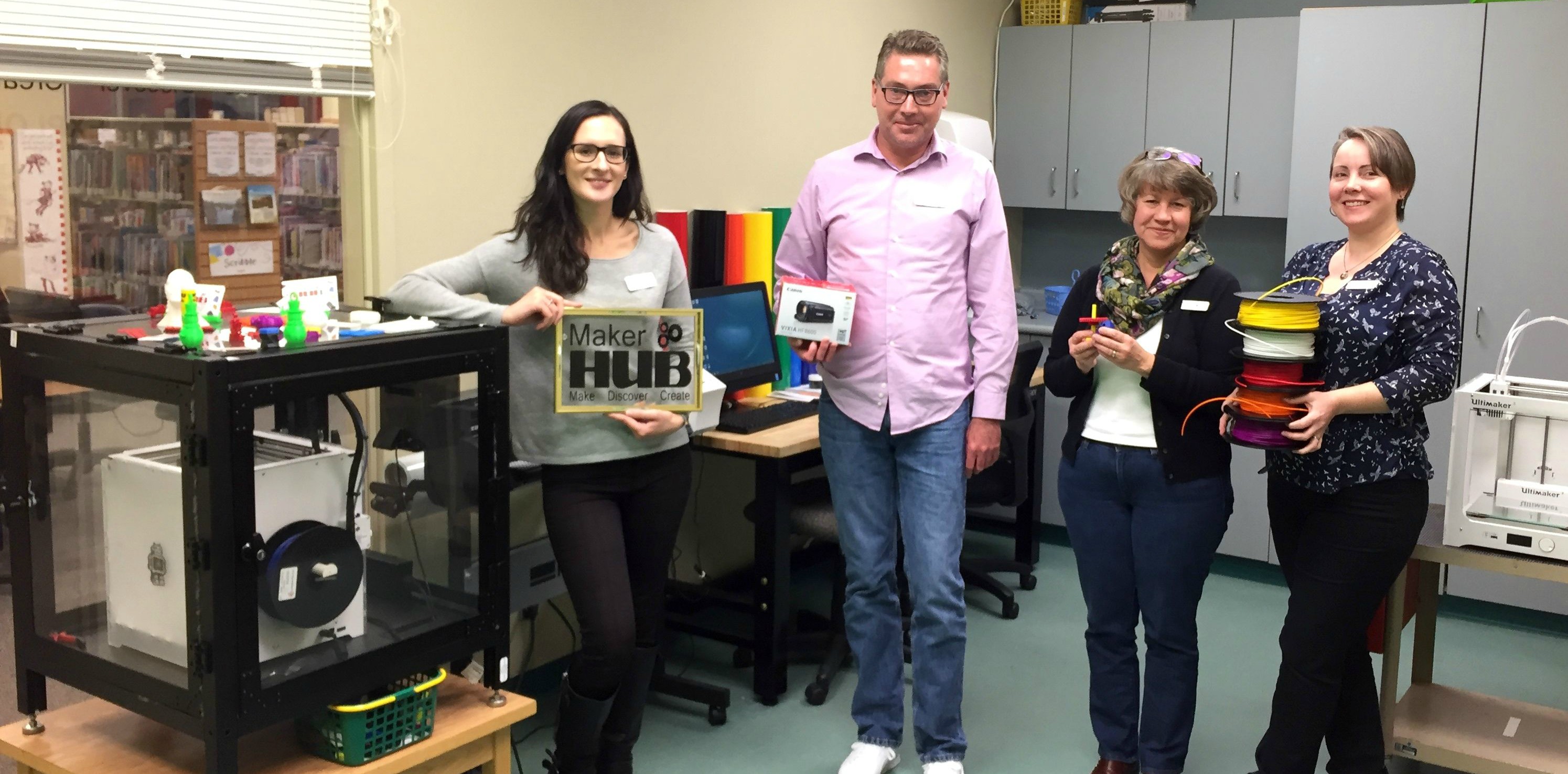

Left to right: Se Da Silva, Michael Russell, Joan Sloan and Caroline Andersen-Gronow, a few members of the Newmarket Public Library staff committee who helped recommend the original technology purchase and are working on drafting a makerspace charter (photo credits: Newmarket Public Library).

Draft a makerspace charter

Although we have access and use procedures for our makerspace, I think we could benefit from drafting a makerspace charter that prioritizes the technology as a resource over a service. Such a statement could ensure that our makerspace is identified as a learning space—signally to others what it stands for and why it deserves support—and to guide us further in a number of areas, including collection development.

Collection development is critical in this context because makerspaces are increasingly a collection of varied technology. There are so many possible suitable purchases now; you need to start thinking about what not to add. As Jennifer Brown states, her team had to “resist the urge to buy tech simply because it was “cool.”

So, at my library, our next step is to begin drafting a charter. This coming fall, we will use MediaSmarts digital literacy model to frame our conversations and write the draft. And we will share the results with the OLA community next spring.

PS: Curious what Jennifer thinks … read her response in this issue!

Photo credit: Dev Benjamin on UnSplash

Michael Russell is the Digital Services Librarian at Newmarket Public Library.