Learn about the benefits of constructing a multi-year internship from a MLIS student's perspective.

Enriching learning through game-based pedagogy

Charlie Brown knows that games are powerful spaces for learning—how to win, lose and be a hero either way.

No doubt academic librarians Amanda Wheatley and Ruby Warren agree with Charlie, but they might put it a bit differently: Games can increase learner attention and retention. Both Ruby and Amanda use game-based pedagogy in their work with undergrads, and here’s their conversation about making their teaching more playful and more effective.

How did you become interested in game-based learning?

Ruby Warren (R.W.)

Gaming (i.e., playing electronic games) has always been an interest of mine, and I frequently used games to incentivize my own work and my learning. It stood to reason that if I enjoyed gamifying my runs with apps that told more stories the farther I ran, or motivating myself to do my readings with a habit-tracking game that gave me a character to level up, other adult people would probably also enjoy using games to learn research skills. I don’t directly teach classes, so I tend to work towards broader, asynchronous digital games rather than in-class games or teaching aides.

Amanda Wheatley (A.W.)

Like Ruby, I have always been a lover of games, both at home and at work; however, my love really flourished during my undergraduate years. I was exposed to a lot of gamified (i.e., applying game-like principles to non-game entities) teaching techniques (including role-playing, card games, digital games, etc) that inspired me to pursue this approach, and I sought out any opportunity to develop my knowledge and my skills in gamification. As an academic librarian, instruction is a huge part of my job, and I’m fortunate that I get to work in institutions that encourage game-based learning so I can apply these ideas to my own teaching.

Why do you think game-based learning works (and in what context)?

A.W.

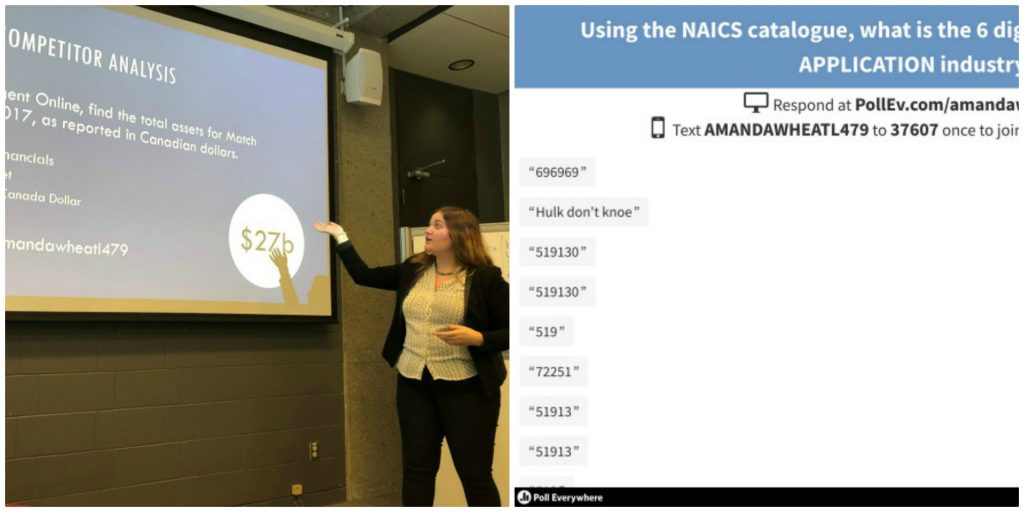

Game-based learning feeds our curiosity and our desire for play and for competition. I’ve found that this approach to teaching allows my students to open up and to engage with the material in new and exciting ways. Students these days are used to being challenged and captivated by technology from an early age. A game allows them to connect with the material and to turn it over like a puzzle in their minds. For me, I know a game works when the students start debating the material or challenging the answers. These forms of engagement show me that the students are truly invested and are willing to learn.

R.W.

I think game-based learning works because it motivates learners (i.e., learners can recognize that they are being asked to complete an activity, which provides either extrinsic or intrinsic rewards) and also because it increases a learner’s awareness of and engagement with concepts. Game-based learning works best when I’m teaching skills, as it provides a low-stakes way for learners to practise behaviours. For example, teaching basic research skills is a good subject to gamify. Learners can then experiment with the risks and the rewards of different research approaches without having to experience strong negative consequences (like a bad grade).

What is your favourite game-based approach to learning?

A.W.

I’m a competitive person, meaning any game where I’m put head-to-head against a team or an individual is going to fuel my drive to succeed. As a business librarian, I find that my students also tend to be very competitive. This discovery means I get to design games that keep my students active and full of adrenaline. I use a mix of digital and physical games depending on the instruction content. Currently, I am designing an information literacy obstacle course. My favourite approach is any that gets the user moving and forming an emotional attachment. I often like to pair a small lecture with the games and to finish off a session with a discussion about what everyone has learned.

R.W.

My favourite game-based approaches to learning are perhaps unconventional—I’m interested in the ways people are trying to apply game-based learning to the development of emotional intelligence, co-operative skills, and empathy. For examples of this approach, Brenda Brathwaite Romero’s Train is very interesting, as are Anna Anthropy’s Keep Me Occupied and Dys4ia

Anything else to add?

R.W.

Don’t be afraid to experiment and to try teaching and learning through games. The best thing about games is that they allow us a safe space to challenge ourselves, to grow and to internalize lessons that make us better and more capable people.

A.W.

I agree! Game-based learning is not a scary concept; in fact, I have almost as much fun watching my students play as I do designing the games themselves. My advice for people looking to try this type of learning is to step back and to think about what games they enjoy and why. From there, the rest is just a spark of imagination.

Feature photo credit: Val Vesa on Unsplash

Collage photo credits: (Left) Photo by rawpixel on Unsplash and (middle) Kushagra Kevat on Unsplash

Ruby Warren believes in the power of play and that learning is a lot more effective when it’s interactive. She is the User Experience Librarian at the University of Manitoba Libraries, where she recently completed a research leave focused on educational game prototype development and has been playing games from around the time she developed object permanence.

Amanda Wheatley is the Management, Business and Entrepreneurship Librarian at McGill University. Her professional interests include entrepreneurship, marketing, information literacy, digital scholarship, and gamification. Amanda enjoys quiet evenings spent playing board games or Mario Kart that quickly devolve into chaos and madness.