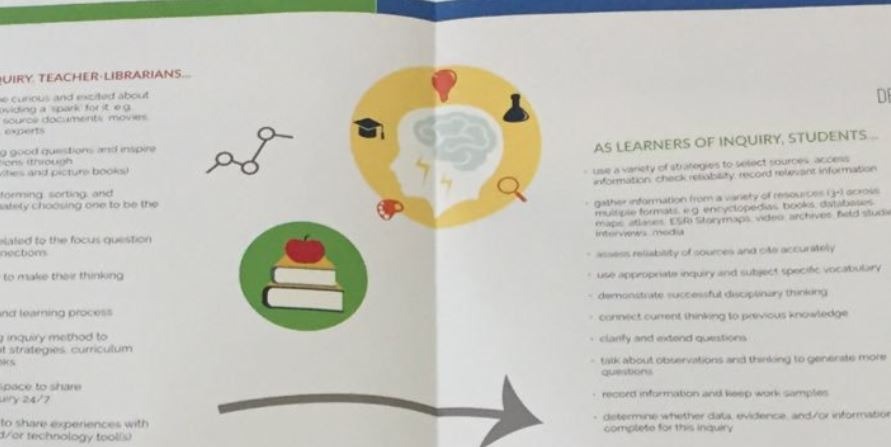

I am intrigued with the work of fabulous secondary teacher librarian, Jonelle St. Aubyn. Her practice is both familiar and innovative.

I won’t be levelling the library … and here’s why

As an elementary school teacher, I recognized very early in my career that the pressure to teach young students to read weighed heavily on me. Beginning as a Grade 1 teacher, I became keenly aware that I had the tremendous responsibility and the incredible privilege of ensuring the children learned to read. I have spent the rest of my career (regardless of my teaching assignment) trying to figure out exactly what that means.

Before anyone panics, I have a wealth of training and have done (and continue to do) a plethora of professional reading on learning to read and on literacy development. But the reality is that even the experts cannot quite agree on the “just right” approach. I recall conversations about and articles on the “reading wars” including the phonics–whole-language instruction debate. This and other battles continue today, with various experts weighing in on the science of reading, fostering love of reading, the best methods of reading intervention and more. The simple internet search “how to teach a child to read” produces about 310,000,000 results in 0.63 seconds. Talk about overwhelming!

So where does the elementary school library learning commons fit in to this debate?

According to the Canadian School Libraries foundational document, Leading learning, one of the goals of the library learning commons in literacy development is “fostering literacies to empower lifelong learners.”

New technologies and evolving methods of communication and sharing drive expanding understanding of literacy. This reality has made the refinement and demonstration of strong literacy skills ever more important for learners. Exploring and connecting various ways of knowing and learning is part of the process of personalizing learning and involves embracing new literacies and skills. The school Library Learning Commons has a leading role in assisting learners to hone and apply an expanded notion of literacy as well as fostering an active reading culture. [2014, p. 17]

Nowhere in this description do the creators of this document suggest that we assign reading levels to the books on our library shelves and restrict student access based on grade or assessed reading level. But I can tell you that not one year of my career as a teacher-librarian has gone by without at least one colleague, student, parent or caregiver asking me to do just that.

“Where is the section with the Grade 3 books?”

“My teacher says this book isn’t hard enough for someone in Grade 7.”

“My mom says I can take home only books I can read all by myself.”

“Do you know where the Level F books are?”

“I want to learn about dinosaurs, but I can’t read all the words, so I can’t take this book home.”

For some additional context, assigning reading levels to books plays an important role in classroom-based guided reading instruction and in helping to determine student strengths, existing reading behaviours and a student’s ability to both decode and comprehend text. But even Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell, two of the most well-known creators of levelled materials, very clearly state that these levels are meant only to be teacher tools and should never interfere with a student’s opportunity to self-select books based on interests and passions. Fountas and Pinnell’s blog post entitled “A level is a teacher’s tool, not a child’s label” delves deeper into this important discussion.

For some additional context, assigning reading levels to books plays an important role in classroom-based guided reading instruction and in helping to determine student strengths, existing reading behaviours and a student’s ability to both decode and comprehend text. But even Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell, two of the most well-known creators of levelled materials, very clearly state that these levels are meant only to be teacher tools and should never interfere with a student’s opportunity to self-select books based on interests and passions. Fountas and Pinnell’s blog post entitled “A level is a teacher’s tool, not a child’s label” delves deeper into this important discussion.

Self-selection of text in the school library learning commons fosters love of literacy and lifelong learning. Gone are the days where we restrict our kindergarten students to board books or to the simplest picture books because the children cannot decode the text or because they might inadvertently damage a book. Gone are the days where we tell the Grade 6 student who loves graphic novels that those books do not count as “real reading.” Gone are the days where we think that narratives shared in picture books are just for primary students and that non-fiction texts are only for older students who have mastered the mechanics of reading independently.

In the Australian edition of The Huffington Post, an article on the decline in reading for pleasure amongst school-aged children states:

An overwhelming majority of kids agree that their favourite books—and the ones they are most likely to finish—are the ones they choose themselves, and nearly three-quarters (74 percent) say they would read more if they could find more books that they like. [Charleston, 2016]

Hey @castleoaksps – don’t forgot our #whatareyoureading campaign is running all year! Send Mrs. Brown your pictures with whatever you are currently reading or post them as a reply to this message! Books, blogs, audiobooks, magazines, websites, newspapers etc all included! pic.twitter.com/1wQg89cgYx

— CastleOaks Library (@CastleOaksLLCs) February 12, 2019

Commonplace articles and studies like these teach us that school itself has the potential of killing love of reading. One idea often repeated, along with the importance of children self-selecting a text, is showing children that we, as adults, also read for pleasure. Children need to see that we parents, caregivers and educators pick up a novel or a newspaper or a non-fiction book or listen to an audiobook or read a blog or an online magazine simply because it inspires us or makes us laugh or helps us learn something new. Our school has chosen to embrace #whatareyoureading on the library social media accounts to show our students that outside of the requirements of our classrooms and our jobs, we all should read for pleasure. Staff, students and families share a picture of their latest read to encourage a love of reading in all forms.

So … no … I won’t level the library or restrict access to the books the children are curious about. But I will encourage children to explore an interest that’s important to them, to wonder about the world and to engage meaningfully with a book they choose themselves.

Slider photo by Jonas Jacobsson on Unsplash

Jennifer Brown is a teacher librarian with the Peel District School Board at Castle Oaks Public School in Brampton and currently the president of the Ontario School Library Association. You can read more of her thoughts about issues in education, social justice, school libraries and more by following her Twitter account @JennMacBrown or her blog “Finding The Magic”.