Learn about the benefits of constructing a multi-year internship from a MLIS student's perspective.

Taking responsibility: Why state imposed governance for Indigenous Peoples?

By Andrew Gemmell and Martha Attridge Bufton

In this two-part article, Andrew and Martha unpack the supposed abrogation of responsibility of the federal government to Indigenous communities. In this first installment, they dive into the question of governance and the tensions between the Indian Act and rights created under both the Constitution of Canada and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

“Canada has gradually ceded its oversight powers to band chiefs and councils, without checks and balances, or any semblance of accountability.”

Cede, oversight, “checks and balances,” accountability—in a single sentence, journalist Diane Francis frames the relationships between Indigenous Peoples and the Canadian state with language that supports and reinforces colonial governance structures.

Many of us may not have an extensive understanding of Indigenous-federal relations, so we might ask ourselves, “What is so problematic about a vocabulary of good governance?” We might also wonder where we would start to search if we wanted to find the kind of information that might provide a counterpoint to Francis’s idea that the Canadian federal government needs to take back its power from Indigenous communities.

In what follows, we sketch some key points that help frame the problem. We also offer some “information seeking” suggestions—ways of finding key documents that frame ideas about governance in the context of Indigenous-state relations.

Finally, we invite Kahente Horn-Miller into the conversation. Kahente is a leading Kanien’kehá:ka scholar who thinks deeply and critically about issues of governance.

Simple statements about complex problems

Just to recap.

In her recent opinion piece The Federal Government has Abrogated Its Responsibility to Hold First Nations Accountable, journalist Diane Francis argued that the federal government has violated its legal duty to hold First Nations band councils financially accountable, infringing the rights of band members. To construct this argument, Francis opens with the unsourced claim that First Nations “often do not” consult their constituents. As a result, First Nations governance is plagued by a lack of accountability and corruption and is therefore profoundly undemocratic. According to Francis, the root of this problem is twofold.

One, First Nations are incapable of independent governance; and two, the Trudeau government is derelict of its duty to hold them accountable. This combination of a lack of capacity and a lack of responsibility ultimately violates the rights of band members.

As with many simple statements about complex topics, there are both elements of truth as well as deeply problematic aspects to Francis’s opinion.

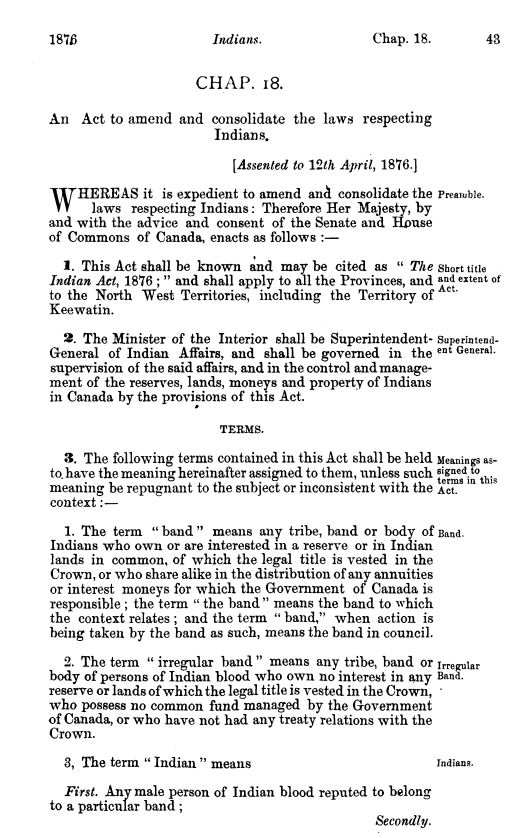

On the one hand, it is true that the Canadian federal government has a legally enforceable fiduciary obligation towards Indigenous peoples. This obligation emerges from the Indian Act of 1876 (“the Act”) , a piece of federal legislation that consolidated the relationship between the federal government and Indigenous peoples in Canada. This statute has been amended numerous times over the decades, but its principal role is to unilaterally define:

- Who is an “Indian”;

- The land (or lands) to which Indians might be entitled (“reserves”); and

- How they are allowed to organize themselves (“bands”).

On the other hand, the Act’s comprehensive control of Indigenous life and identity in Canada is profoundly problematic.

Wards of the state

This legislative control of Indigenous peoples in Canada makes “Indians” wards of the state who have been systematically oppressed. For example, in recent years numerous amendments have tried to resolve the Act’s gender discrimination, which defined many Indigenous women and their children as no longer “Indian”. Along similar lines, The Truth and Reconciliation Commission described the residential school systems, established under the auspices of this legislation with the intentions of eliminating Indigenous cultures and identities, as one that legitimized “cultural genocide”.

This legal framework is further solidified by the embedding of the Act in section 35 of the Canadian constitution and section 25 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Constitution Act (1867 – 1982)

Rights of the Aboriginal Peoples of Canada

Recognition of existing aboriginal and treaty rights

- 35. (1) The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.

- Definition of “aboriginal peoples of Canada”

(2) In this Act, “aboriginal peoples of Canada” includes the Indian, Inuit and Métis peoples of Canada.

Land claims agreements

(3) For greater certainty, in subsection (1) “treaty rights” includes rights that now exist by way of land claims agreements or may be so acquired.

Aboriginal and treaty rights are guaranteed equally to both sexes

(4) Notwithstanding any other provision of this Act, the aboriginal and treaty rights referred to in subsection (1) are guaranteed equally to male and female persons. (96)

Commitment to participation in constitutional conference

35.1 The government of Canada and the provincial governments are committed to the principle that, before any amendment is made to Class 24 of section 91 of the “Constitution Act, 1867”, to section 25 of this Act or to this Part,

- (a) a constitutional conference that includes in its agenda an item relating to the proposed amendment, composed of the Prime Minister of Canada and the first ministers of the provinces, will be convened by the Prime Minister of Canada; and

- (b) the Prime Minister of Canada will invite representatives of the aboriginal peoples of Canada to participate in the discussions on that item. (97)

Charter of Rights and Freedoms

Aboriginal rights and freedoms not affected by the Charter

- The guarantee in this Charter of certain rights and freedoms shall not be construed so as to abrogate or derogate from any aboriginal, treaty or other rights or freedoms that pertain to the aboriginal peoples of Canada including

- (a) any rights or freedoms that have been recognized by the Royal Proclamation of October 7, 1763; and

- (b) any rights or freedoms that now exist by way of land claims agreements or may be so acquired. (94)

Anishinaabe jurist John Borrows describes the Act’s enshrinement in these two key legal documents as “a perverse colonial framework”. Similarly, Heidi Stark, an Anishinaabe legal theorist, notes that this legal “double jeopardy” perpetuates a colonial “logic of containment [that] operates as an extension of the epistemological and physical violence endemic to settler colonialism”.

Jody Wilson-Raybould, Canada’s first Indigenous Minister of Justice and Attorney General, believes that the cumulative effect of legislative control places the federal government in a “dilemma” that she calls “the tragedy of ‘wardship”.

Simultaneously, the colonial government has a legal obligation to act on behalf of its wards while also striving to dismantle racist and genocidal colonial structures of domination and exploitation. For Wilson-Raybould, this means “building strong and appropriate First Nations governments,” within what she calls “fiduciary gridlock”.

Recognizing that there is an alternative perspective, i.e., that the federal government is caught in a “fiduciary gridlock” rather than in an abrogation of responsibility, can suggests that Francis’s position is fraught with loaded assumptions.

- When Francis demands accountability from band councils established by the Indian Act, she is assuming the validity of the forms of governance embedded in the Act. Neither Francis (nor the law) make mention of the traditional forms of Indigenous governance that in fact the federal legislation actively ignores and has tried to eliminate (oftentimes with violence).

- Although the federal government has a legally enforceable fiduciary obligation to First Nations, the relationship of guardian to ward is profoundly problematic. Francis assumes that this relationship should be reinforced, and not everyone agrees.

- Finally, Francis repeatedly asserts that the Trudeau government’s abrogation of its responsibilities to Indigenous peoples infringes upon the Charter rights of Indigenous peoples; I think that there is more to the story. As Francis states, it is true that Indigenous peoples in Canada enjoy Charter rights as established by Section 15, which protects the equality of all citizens before the law. However, there is a tension between the individual rights of section 15 and section 25, which limits section 15 such that this second section cannot “abrogate or derogate from any aboriginal, treaty or other rights or freedoms that pertain to the aboriginal peoples of Canada”. As Aboriginal and treaty rights are collective rights, and section 15 rights are individual, there is a fundamental tension between the two. Francis wants Section 15 to override Section 25 (which is unconstitutional).

Information seeking: Finding relevant government documents

While many library staff are comfortable navigating the (sometimes) complicated world of government documents, some of us are not. For example, as an academic librarian, I (Martha) can find peer-reviewed journal articles quite easily. However, responsibility for government documents has traditionally been given to librarians and subject specialists who have specific expertise in this area. As a result, when I have been asked a reference question related to finding legislation, typically I have cheerfully and swiftly referred patrons to my government documents or legal librarian colleagues.

But what if someone has to or wants to try and “information seek” on their own? Here is some strategies for finding the key legal documents to which Francis refers:

- The Indian Act (original and annotated version)

- First Nations Financial Transparency Act

- Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

- Constitution Acts (consolidated)

Step one: Finding the current versions of legislation

The Justice Canada laws site or CanLII (the Canadian Legal Information Institute) are open-access sites where it is relatively easy to do basic or advanced search laws by name, by jurisdiction, and/or by type.

As such, finding all four pieces of legislation can be done either in a library or from the comfort of one’s home device. However, finding the original version of a law that received approval (i.e., Royal Assent) in the 19th century can be a bit trickier. Particularly tricky if someone is interested not only in the legislation itself, but in the discussion and thinking that took place amongst law makers as they were considering a bill.

Step two: Finding the historical versions legislation

According to Carleton University law librarian Julie Lavigne, two tools are particularly helpful when doing this type of historical research:

- Canadiana Online

- I started with Canadiana Online and did a key word search for “Indian Act.” From the results, I was able to identify the fact that the Indian Act of 1876 was introduced as a bill and received royal assent that same year, in the third session of the third Parliament.

- Julie points out that while Canadiana is an excellent repository of older, historical documents, it does not offer many filters for identifying the types of documents that might be relevant to a search.

- The Parliament of Canada website, and specifically the Parliamentary historical resources provided by the Library of Parliament.

- Julie guided me through this website starting from the House of Commons link > Parliamentary business (under the menu box, top right) > Resources > Parliamentary Resources (1867-1993).

- From here, I could search for the debates (i.e., what were parliamentarians saying as they consider the “Act to amend and consolidate the laws respecting Indians”), the journals (the official record of the decisions and other activities that happen in the House of Commons) and the committee review (if any) related to the passing of the bill.

Using this two-pronged search strategy, I could follow the parliamentary discussions related to the Indian Act of 1876, that actually began on February 10, 1876 and culminated on April 12, 1876 with royal assent.

Connect and consult communities

Even with the legal documents in hand, anyone trying to make sense of Francis’s argument would also benefit from learning more about the issues from an Indigenous perspective. In general, respect and justice are important principles to follow when building relationships with Indigenous Peoples and communities.

In addition to building respectful connections with Indigenous communities according to community protocols and traditions, one could also try to connect with Indigenous scholars who might be willing to engage in conversations about these issues. Legal scholars Heidi Stark and John Borrows have already been mentioned and they have published on a range of topics. Granted, their publications may not be available through public libraries but, in many communities, patrons can work with the public library staff to try and access academic materials. For example, in Ottawa the Smart Card program makes it possible for the public to borrow books from local university libraries. In addition, there might be Indigenous scholars doing research and teaching at local institutions who might be willing to be consulted.

On the topic of traditional governance, Prof. Kahente Horn-Miller is actively writing about governance in her community of Kahnawake. As she states in the following short video, governance as traditionally defined by Indigenous Peoples is something “entirely different” from governance as defined in the Indian Act. These differences are significant and cannot be ignored. Prof. Horn-Miller is a teacher and researcher in the School of Indigenous and Canadian Studies at Carleton.

Transcript Prof. Kahente Horn-Miller: On governance

Further reading

Horn-Miller, K., (2018). How did adoption become a dirty word? Indigenous citizenship orders as irreconcilable spaces of Aboriginality. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 14(4), 354–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180118802861.

Andrew Gemmell (MA Philosophy, NSSR; PhD student, SICS and Institute of Political Economy, Carleton University) brings a background in philosophy and critical theory to his work on Indigenous-newcomer histories and institutions and settler colonialism in the Canadian context, which focuses on the formal structures of settler colonial responsibility and accountability.

Martha Attridge Bufton (MA, MLIS, Graduate Certificate in TBDL) is the Open Shelf editor-in-chief and a member of Editors Canada. Martha is the Interdisciplinary Studies Librarian in Research Support Services at the Carleton University Library and supports faculty and students in the School of Indigenous and Canadian Studies. She can be reached at martha.attridgebufton [at] carleton.ca.