Learn about the benefits of constructing a multi-year internship from a MLIS student's perspective.

Knowing ourselves: How the Encyclopedia of Canada’s Peoples can help us learn who we are

In a COVID-19 blindsided world where we’re struggling to make content available to students, what’s the value of online reference materials? So, what’s my answer to this pressing question? Online reference materials have huge value! Moreover, I have a suggestion for librarians grappling with pleas from professors for comprehensive resources to support e-teaching—resources that not only provide appropriate and relevant historical content, but can also be used in creating student assignments. My suggestion is to consider the online version of the Encyclopedia of Canada’s Peoples—this is a resource from which we can learn a lot about ourselves both locally and nationally.

I’m a contract instructor in the history department at Carleton University, so I’ve been asking myself this question about online resources a lot lately. Of course, the context (for my colleagues and me) is the need to shift from in-person to virtual classrooms and the challenge of finding high quality resources to integrate into curricula in these new settings. Also, pervading everything we do and hope to accomplish is our renewed commitment to advancing equality for racialized and Indigenous Peoples. The Encyclopedia of Canada’s Peoples is a resource that can support this commitment in the classroom because it offers relevant content that is broad and deep in scope.

The University of Toronto Press published the print version of the Encyclopedia for the Multicultural History Society of Ontario (MHSO) in 1999. Two years later, it designated the Encyclopedia as “one of the 100 most influential and important books” that it had published in its 100-year history. In my estimation, the Encyclopedia continues to stand the test of time in terms of both its content and the messages it relates. The Encyclopedia helps us learn who we are by tracking the fault line of inequality in Canadian history.

I’ve long felt that librarians should be better acquainted with the Encyclopedia, especially now that the MHSO has made an online version available. Word of honour! The idea of writing this article was formulated before recent, urgent discussions about racism in Canada. Initially, I was hoping to introduce the university library sector to an important resource that will be useful in the move to e-teaching. But, given current events, increasing awareness of the Encyclopedia is even more important now. My reasoning? It can help us learn who we are.

We’re all aware of the mantra that cultural pluralism is central to Canadian identity. Perhaps we’re skeptical of defining national narratives. However, this narrative has emerged out of our histories of migration, ethnicity and Indigeneity, and the demographic and sociopolitical realities they produced. As we examine and reimagine our relationships with one another, it’s crucial that we become more knowledgeable about the nuances and complexities of our various historical experiences. The Encyclopedia is an excellent aid in this task.

The Encyclopedia was years in the making and involved the efforts of more than 300 scholars from across Canada who served as authors, consultants and advisors. According to Elizabeth Price, the MHSO’s Development Manager and a one-time work colleague at the Ontario Heritage Foundation, it was modelled on the Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups and The Australian People: An Encyclopedia of the Nation, its people and their origins.

The Encyclopedia project was initiated to fill an obvious gap in Canadian reference material. It was also undertaken in an effort to build on the legacy of Robert Harney, Milton Israel, Pierre Savard, Frank Iacobucci, and several other close colleagues, founders of the MHSO in the 1970s. They were convinced that chronicling our diverse stories was essential to understanding Canada in the 20th century and beyond. Those stories aren’t, of course, fixed. Their meaning and impact evolve and resist endings. Consequently, the MHSO plans to update entries in the online version of the Encyclopedia at intervals comparable to the Harvard and Australian models. (Actually, the former, published in 1980 and still in print, hasn’t been updated yet.)

The Encyclopedia is a comprehensive reference work and research tool that describes the experiences of 119 different peoples/ethnic groups. The massive publication (the hard-copy version, the basis for the MHSO’s online resource, was 1340 pages) contains individual entries on, among others:

- Indigenous Peoples

- French

- English

- Blacks

- Chinese

- Jews

- Ukrainians

- Vietnamese

Each entry covers key information such as the origins of the people/group, the process of migration, arrival and settlement, economic and community life, family and kinship patterns, language and culture, education, religion, politics, intergroup relations and the dynamics of group maintenance. Thirteen thematic essays are also included to illuminate complex issues related to immigration, assimilation, multiculturalism and Canadian culture and identity.

One of the main ways that the reconciliation agenda can be accomplished in Canada is to have non-Indigenous peoples learn more about Indigenous Peoples. With this in mind, I find the 12-part entry on Indigenous Peoples, produced under the supervision of renowned Métis historian Olive Dickason, to be a particularly striking feature of the Encyclopedia. The sub-entries are based, for the most part, on major linguistic groupings, and each discusses various nations, pointing out their unique characteristics and histories.

The annotated bibliographies that accompany the entries are another striking feature of the Encyclopedia. The bibliographies are solid on their own, but they can also be used as a starting point for important research work, especially in college and university settings.

To cite one example, in my teaching at Carleton University, I intend to introduce my first-year Canadian History students to the publication.

I will have them take the existing bibliographies and build on them with secondary research that has been undertaken since the Encyclopedia’s release. (With some exceptions, there’s relatively little, unfortunately.) I’ll ask students questions such as:

- What research has been undertaken on the group since 1999? How does this research differ from what preceded it, and why do you think this is the case?

- If little has been written since 1999 on a particular group, what possibly explains the dearth?

- Have considerations such as class, gender, and region been incorporated into the recent research? If so, what insights can this offer to readers?

In terms of better understanding ourselves, three thoughts (among many others) occur to me.

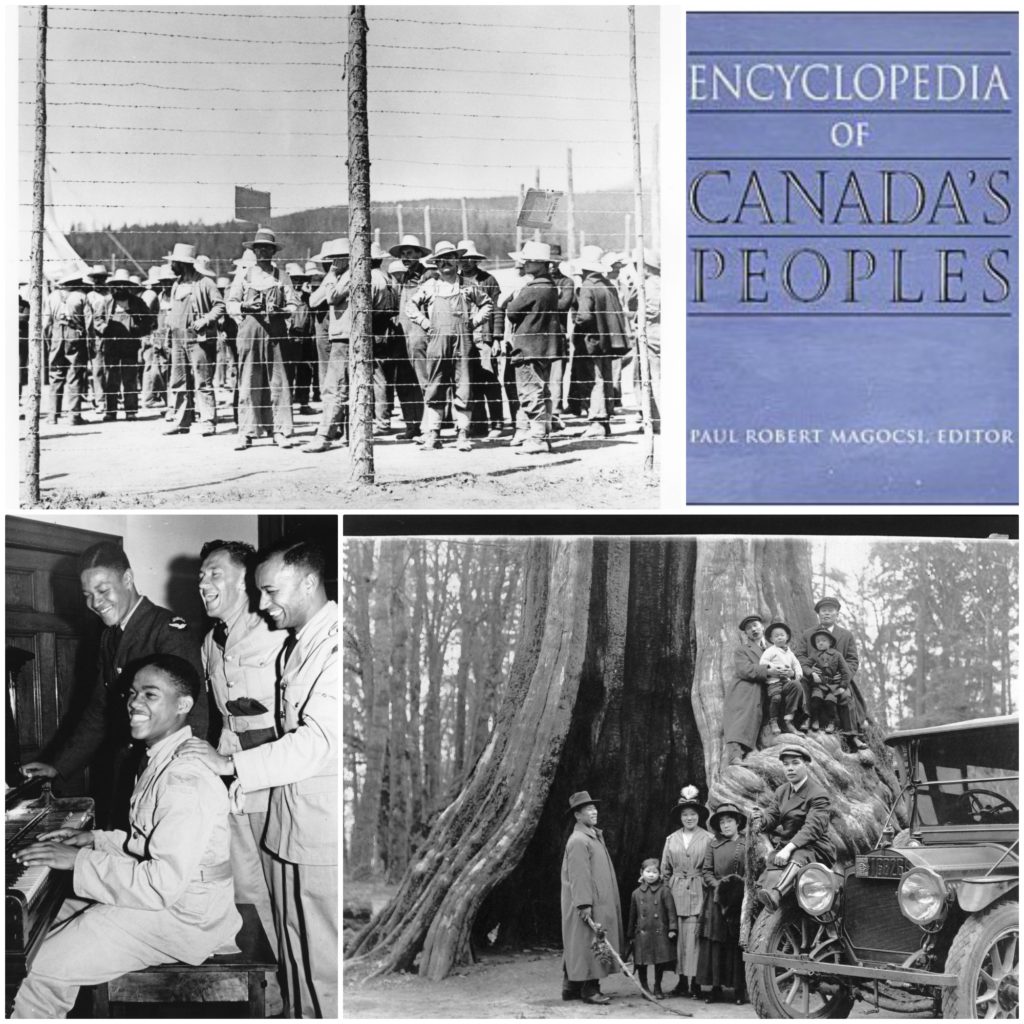

First, the Encyclopedia can be used to convey historical nuances and complexities by juxtaposing standard accounts of decisions and events in our past with the actual historical experiences of ethnocultural, racialized and Indigenous communities. Public perceptions of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War era versus their actual experiences is but one example that comes to mind.

Second, we can convey and interpret our past through a focus on, and examination of, specific themes. Examples include the development of our political institutions and political culture, the increasing power through time of capital, and the evolving role of the mass media. The Encyclopedia can provide an entry point to our past through a focus on, and examination of, the themes of migration and identity formation.

Third, the Encyclopedia can help us learn who we are, since it can facilitate tracking of a significant dynamic or fault line in Canadian history: inequality. Many examples illustrating components of this dynamic—marginalization, oppression, violence—can be drawn from Encyclopedia entries.

In all of the above, the structure of the Encyclopedia calls out to students to complete studies/assignments in comparative history. I gather, from reviewing the teachers’ guide produced to accompany the publication, that the MHSO has assisted, and continues to assist, educators in understanding and addressing commonalities, as well as variances, across different communities in different times and places.

For these and many other reasons, I think the online version of the Encyclopedia should be a part of any library (academic and otherwise) that wishes to offer students—indeed, all patrons—the opportunity to know themselves better.

I hope to raise awareness of the Encyclopedia because I believe that it’s the type of resource to which librarians can refer patrons who are making sincere efforts to understand other peoples in our country. It’s also, in my view, a valuable resource for librarians who wish to become more knowledgeable about cultural pluralism in Canada so that they themselves can be better informed and thereby provide even better service to their patrons than they already do.

Kerry Badgley is the Open Shelf story editor. He is a member of the North Grenville Public Library Board, and in the past served as its president. He currently serves as a board member of the Southern Ontario Library Services.

For more information and for pricing and access details, please contact the Multicultural History Society of Ontario at info@mhso.ca or (416) 979-2973.