Learn about the benefits of constructing a multi-year internship from a MLIS student's perspective.

Library and museum support for the Ainu People of Japan

“The word research is probably one of the dirtiest words in the indigenous world’s vocabulary.” While Maori Scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith (1999) is speaking directly to those who gather data, she is also sending an important message to those of us to collect and provide access to research: Institutional practices have to change if we are to foster respectful relationships with Indigenous Peoples, and these changes have to occur around the world.

This two-part article features the thinking of two Japanese professionals on the role that libraries and museums in Japan can play in promoting the knowledge and cultures of the Ainu People.

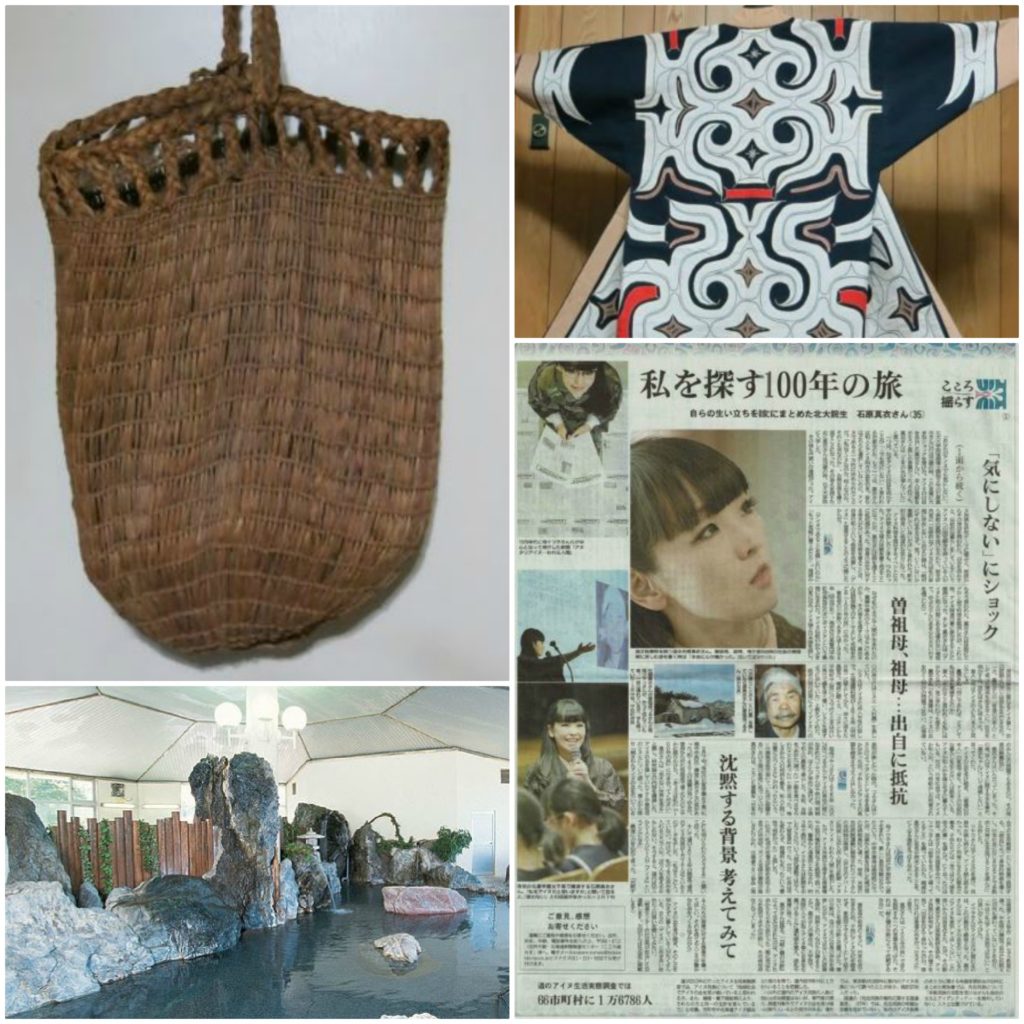

Mai Ishihara is a cultural anthropologist at Hokkaido University, and Yukiko Kamemaru is a curator at the Hokkaido Museum. Hokkaido is the most northerly island in the Japanese archipelago and home to the Ainu People. Mai and Yukiko both presented at the IFLA World Congress last August in the Indigenous Matters session entitled Gulahallan, Gishiki, tikanga: Creating Dialogues, Fostering Relationships, Promoting the Expression, Activation and Vitality of Indigenous Languages, Knowledge and Cultures.

In Part I, Mai shares her own Ainu history and suggests that Japanese libraries would do well to follow the example of the Xwi7xwa Library, located at the Unviersity of British Columbia, and make space for Indigenous knowledge and perspectives.

In Part II, Yukiko talks about the role that museums have played in misrepresenting the Ainu and proposes that partnerships between libraries and museums could do much to promote greater respect for and understanding of the Ainu Peoples.

Both installments are excerpts from their 2019 IFLA presentations.

Martha Attridge Bufton

Editor-in-Chief

Open Shelf

Reference

Smith, L. (2012). Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (2nd ed.). Zed Books.

Part I: Listening to silent voices and seeing blind spots: Libraries as places where diversity is welcome

By Mai Ishihara, cultural anthropologist and assistant professor (Hokkaido University)

“I am not an indigenous or Ainu person, which means a member of Ainu community. My grandmother on my mother side was Ainu, but I was born and raised in Japanese society as Japanese . . . my family history of my grandmother is very important for me so I don’t hide it. But I am not Ainu . . . calling me Ainu is not based on a discrimination perspective but rather with good intention. But the choice of word is wrong for me.

My history is the history of “disconnection”. I’m not connected to the history, story, knowledge and community. If not, then am I a majority Japanese? If I never tell people about my indigenous background I would be, but I don’t want to hide my grandmother’s history. In becoming open with my hidden history, I find that I exist nowhere, i.e., in neither the Indigenous community not in majority Japanese communities.

A brief Ainu history

The Ainu are Indigenous People in Japan [and] mainly live in Hokkaido, [although] they also live in Sakhalin, the Kuril Islands, and the Northern part of mainland Japan…during the Yayoi Period which started in mainland Japan about 300 B.C., the archaeological cultural periods on Hokkaido included the Zoku-Jomon Period (340 BC–700 AD), the Satsumon Period (700–1200 CE) and the Okhotsk culture (600–1000 in Hokkaido).

The close relationship between the Ainu and the Japanese began in the mid-1400s [when] the Japanese came to oppress the Ainu. To resist this oppression, the Ainu waged battles in 1457, 1669 and 1789, [and] lost each time. After losing the Battle of Kunasiri-Menasi (1789), the Ainu fell completely under the control of the Japanese. In 1869, under the government policy of assimilation, the land of the Ainu was named “Hokkaido”, and the Ainu were prohibited from their customs and began to suffer from discrimination. Some of the discrimination against the Ainu remains today, and research shows there are welfare problems such as poverty and low educational attainment.

“Silent-Ainu”: My family story

The Japanese culture is presented as homogenous, or more simply, a mono-culture, at least on the surface…[and yet], the Ainu lived for centuries in Hokkaido and the nearby Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands. The Japanese Parliament only recently passed a bill to recognize the Ainu as an “Indigenous People who have their own language, religion and culture”. With the monoculture philosophy, neither the concept of otherness, different cultures, people nor history, are taken into consideration.

According to a survey conducted by the Hokkaido Government in 2017, the Ainu population of Hokkaido was a bit over 13,000, based on self-identification. [However], some assume there could be around 100,000 people who have Ainu background across Japan . . . but they are often invisible, silent, and inaccessible. I am one of them.

My mother and very close relatives never utter the word, “Ainu” to each other. When I was 12, I saw my mother raising her voice to her cousin. She said, “I told my husband’s family about my minzokuI didn’t understand the meaning of minzoku so I asked her later what she meant by it. She asked, “Do you really want to know? Won’t you regret to hear it?” I told her I wanted to know, so she told me that my grandmother was Ainu. The reason they used the word Minzoku is because they don’t want to say the word Ainu—it causes too much pain. However, my mother says, “I am an Ainu person, but I am not a member of the Ainu minzoku”.

My mother told me not to tell other people about my background unless the person was knowledgeable about Japanese history, so I grew up with a big secret that I couldn’t tell even to my best friend because not many people are aware of Hokkaido history. I have a non-Ainu (Wajin) father whose ancestor was in the Kotoni colonial troop, the first group of Japanese people to settle and develop the island of Hokkaido. Until I was 12, I assumed I had never met Ainu people. I don’t identify myself as Ainu, but people never accept this explanation and treat me as Ainu since it has become known that my grandmother is an Ainu lady. People tell me that I am refusing my identity or that I am “searching” for my identity; to me, these are very violent comments.

The more Ainu people I met, the more excluded I felt. It is not just about my identity issues, but the social structure that makes me feel very uncomfortable. I needed to know why people never try to hear my “voice”, [so] I started a journey stretching back into 100 years of my family history, to get back my own stolen history.

What I found was that my maternal great-grandmother, who was born in 1904, lived in a traditional Ainu way. She had a tattoo around her lips. This stigmatized her, physically differentiating her from ethic Japanese and identifying her as very alien. She had to hide this tattoo much of her lifetime, for instance in situations like when she had to take a bus. My maternal grandmother Tsuyako was also born in the same village in 1925. She started to work in a non-Ainu Japanese-run farm when she was only eight. Sometimes the only thing she had to eat in the farm was rotten rice. She didn’t even go to elementary school. She never tried to practice any Ainu culture [and] tried very hard to become Japanese because she thought that was the only way to survive and succeed economically in Japanese society. She decided to marry a Wajin man so as to “reduce the percentage of Ainu blood”.

My mother Itsuko didn’t inherit any Ainu culture, but racially she was treated as Ainu, because in her village even with one drop of “blood”, people were recognized as “Ainu”. When she was a young woman, she was involved with Ainu movements and publishing newspapers about Ainu issues, but she felt emptiness. The effect of all this is that the culture inherited in my family for 150 years is the effort and sentiment of “not being Ainu”. For my ancestors, that was the only strategy to survive in Japanese society.

But invisible racism in Japan doesn’t allow those Ainu descendants to become completely “Japanese”. This made us both silent and invisible. We are not completely Ainu, but we are not Japanese either . . . In Japan, especially in Hokkaido, it is very clear one is officially either Ainu or Wajin, but there is no category for what I call “silent-Ainu” or “mixed racial”. By becoming invisible and silent, our history has been stolen from us.

Libraries as spaces for local history and meeting each other

I entered Hokkaido University as a graduate student almost 10 years ago [to do] research [about the] modern Ainu people from a cultural anthropological view. What I found was that most of the books related to Ainu are in research rooms accessible only to professors and graduate students . . . Additionally, there is no presumption that Ainu people would want to use the library. There are no communication spaces in the library nor any opportunities for university members, or citizens, and local indigenous Ainu people to meet.

[This is in contrast to] the Xwi7xwa Library of the University of British Columbia library system . . . I have visited twice, and it was amazing because not only can local Indigenous or First Nations students visit and stay, but everyone can visit and learn about so many things. I have two recommendations for libraries:

- First, if the library could display the history or broader discussion of multiculturalism and the global situation of various minorities including Indigenous People, it would be a great opportunity for multicultural education. To achieve this, it is essential not only to gather books featuring the three F’s frame (fashion, festivals and food), but also to include books from which people can learn the [local] historical background. With this achievement, the entire society would have a chance to be educated about multiculturalism.

- Second, I strongly emphasize that a library can be a space for meeting each other. Diversity is one key to making a creative society. It is not only beneficial for Indigenous or minority peoples. Being able to meet at libraries can also contribute by helping society to reach a broader understanding and acceptance of diversity, and it can create a great source to make a brighter and more prosperous society. A future task is to think about how to make a space that can play this role.

As a silent person of Indigenous descent, I can envision many roles that libraries could hold. It would be a great hope for Indigenous communities, and also for our dramatically changing global society [in order] to consider what could benefit diversity and better multiculturalism.

Mai Ishihara is an cultural anthropologist and assistant professor at Hokkaido University. Her grandmother was Ainu (i.e., an Indigenous person of Japan). Mai is the author of Autoethnography of ‘silence’ : The story of the pain of Silent Ainu and its care. Hokkaido University press (forthcoming).

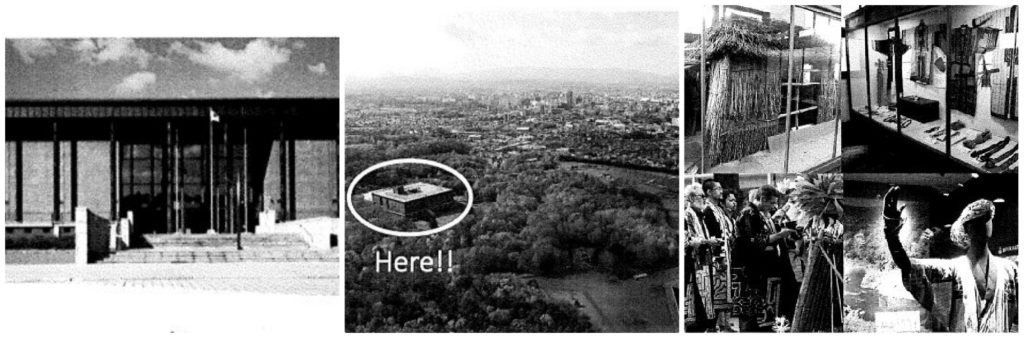

Part II: Real history and real people: Museums and libraires as partners in supporting the Ainu People

By Yukiko Kamemaru, Curator, Hokkaido Museum

I would like to suggest some possibilities of ways in which libraries and museums can work together towards the better use for the Indigenous resource[s] of Japan. These suggestions are based on the idea that both libraries and museums are cultural facilities [that] are widely open for public use. I will talk about this topic from the perspective of a museum curator [and use] examples from my museum, where I curate Ainu articles for everyday use.

Who are the Ainu People? Statistics and stereotypes

The Japanese government has just started to recognize the Ainu People…In 2008, the Japanese parliament said that the Ainu people [are] the Indigenous people of Japan . . . but it was not possible to stipulate this notion in legal documentation. In April 2019, the Japanese government enacted “a new Ainu law” and finally recognized the Ainu as the Indigenous People of Japan.

This is still quite a controversial matter, because the new law did not mention anything about the collective nor land ownership rights which are granted by law in some other countries that have Indigenous Peoples. Additionally, there is a survey on the living conditions of Ainu people in Hokkaido. The survey is conducted by a division of the Hokkaido government and it shows . . . that there are 13,118 Ainu people in Hokkaido and there are more statistics regarding “the life of Ainu people”. These data tend to be recognized as official and…might be a shortcut answer for the many people who have questions like “Where can I go to see the Ainu people?” or “Do those Ainu people still exist in Japan?” and “How many of them?”.

But, we need to know that the survey adopts a questionnaire style, so it is sent to the area where the Hokkaido government assumes Ainu people are living. Plus, the survey can be answered by people who are in favour of the present policy and recognize themselves as Ainu. We need to remember that those numbers reveal one side of the Ainu reality, but also contain the danger of misrepresenting the multiple living diversities of Ainu culture. Another factor causing misunderstandings or stereotypes toward the Ainu people is the school education system. In the Japanese education system, students learn about the Ainu people only as one part of Japanese history and these lessons are always focused on their traditional way of life or on cultural differences from the “Japanese culture”. [This is] quite limited information and these ideas always come from the majority point of view.

Due to majority thinking, many people may have the wrong image of or stereotype towards Ainu or Indigenous People. For example, people still think Ainu are living in a traditional way or they even think the Ainu culture is a thing from the past, which is totally wrong. In emphasizing their traditional way of life with a majority thought, there is a lack of connection from the past to present [and] the historical courses of real Ainu people come to be absent.

Museums and misunderstandings

Unfortunately . . . exhibits at museums [also] make people have misunderstandings towards Ainu people and their culture. In the 1980s, some arguments about intercultural exhibits arose among ethnographical museums all over the world [Yoshida 2014]. They focused on one-sided (in other words, prejudiced) exhibitions that deal with Indigenous cultures. At the time, most Indigenous exhibits at museums were showing only the traditional way of living from the perspective of primitivism. Thus, museum visitors received wrong information about the Indigenous People and it caused much discrimination…sadly, this exhibit style lasted quite a long time. I would say that it can be recognized as the same problem regarding . . . other Indigenous cultures or groups.

People [have now] finally recognized the problems of museum exhibits and started to remove those misunderstandings and stereotypes…There are some movements of cooperation or participation of Indigenous People in creating museum exhibits together, instead of creating one-sided exhibits in the way that people used to. Making an exhibit with Indigenous People would help to fill the gap between the image the majority have and the real life of current Indigenous people.

There are still few Ainu exhibits in other places in Japan besides Hokkaido. Cooperative exhibits have started in the National Museum of Ethnology in Osaka and spread to a few museums but I have to say that the number of cooperative exhibits are still quite limited. Of course, I donʼt think these cooperative exhibits are the perfect answer for the problems. However, we have to realize that these problems and situations are always based on (or caused by) majority-sided viewpoints.

Regarding libraries, [there is] the problem of book classification. In some libraries, books related to the Ainu people or Ainu culture are still categorized as “ethnology” [and the] Ainu culture or even Ainu people are still considered as a part of “Japanese ethnology”. This means that we unconsciously categorize and deal with Ainu people [according to] what the majority think the Ainu are. This causes an avoidance of showing the actual history that has been lived by real people. It is an important fact that the Ainu history still continues to present times.

Unfortunately we, the staff who are working at cultural centres like libraries or museums, donʼt even realize what the majority is doing unconsciously and it can be said that there are only few staff who have knowledge about the Ainu or their culture in Japan . . . I would say . . . libraries could be the best place to show people Ainu and their culture. However, as far as I can tell, there are no connections between libraries and museums.

How can we solve these problems?

In Japan, understanding about the Ainu people and culture faces the difficulty of the many obstacles caused by misunderstandings or stereotypes towards the Ainu. It is quite hard to find the correct information sometimes. To solve these problems, cooperative work between libraries and museums could offer people a way to get understanding or knowledge about the Indigenous People of Japan; Ainu. For example:

- Museums can provide information based on the latest research or specific expertise about Ainu studies. Thus, it might be possible that museums could hold lectures or discussions about Ainu culture for librarians at libraries. After making a relationship with libraries and librarians, it can be possible to publish a bibliography or other guidelines on the Ainu culture for the public. It would be better to have different categories for different generations. Especially for children there could be a picture book reading event in the Ainu language in the near future to familiarize them with the Ainu language, using the skill of how to pronounce the Ainu language correctly, etc.

I hope the cooperation of libraries and museums can be one of the solutions not only for the majority but for the Ainu Peoples as well to have the opportunity to know about and even to help people rethink our recognition towards cultures and identities. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, the national Ainu museum opened in Shiraoi, Hokkaidon July 12, 2020. It is the first national museum for the Northeastern area of Japan and for the Indigenous People of Japan, Ainu. I think it is time to rethink the majority perspective on the Ainu and their culture. I have high hopes for the many roles which the national museum could hold.

Reference

Yoshida, K. (1999). Bunka no Hakken [Discovering Cculture]. Tokyo: Iwanami shoten.

Yukiko Kamemaru is a curator at Hokkaido Museum (April 2018-current). She has a master of literature (museology), which she receive in March 2019 from Hokkaido University.