The thinking of Comrade F. Dobler from the early 20th century remains relevant and even prescient: those who need open access to information may be those who are fundamentally excluded from public libraries.

Intercultural competency

Open for all? offers a “think piece“ rather than an intellectual analysis. Columnist John Pateman shares his personal observations on issues and his columns are designed to promote discussion and professional debate. He has arrived at his conclusions after 40 years of working in public libraries of/in all types and locations.

“Culture is more often a source of conflict than of synergy. Cultural differences are a nuisance at best and often a disaster” (Geert Hofstede).

It is a long time since I went to library school (which is what we called it in the U.K. back in 1979), but I still vividly recall learning the mysteries of cataloguing and of classification. I also learned about managing buildings, staff, collections and budgets. But I didn’t learn anything about the social role of libraries: how libraries can be agencies of social change and of social justice. In other words, I learned the traditional library skill set. I did not learn the skills required to manage a community-led or a needs-based library.

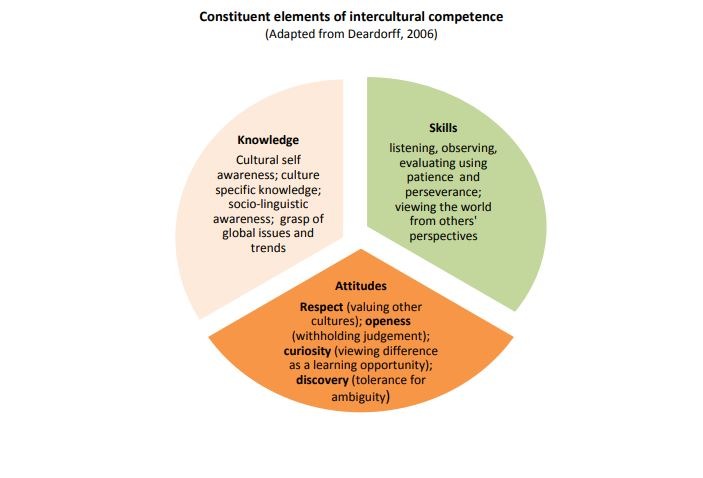

Research at the University of Sheffield (The right ‘man’ for the job) found that the traditional library skill set was woefully inadequate for a modern, relevant public library. It was suggested that library workers need to have the following advanced customer care skills: Communication skills; listening skills; the ability to influence relationships, to exercise reflective practice to achieve improved confidence and assertiveness; negotiation skills; the ability to deal with conflict. I would like to add another skill to this list: Intercultural competence.

There are many benefits to developing intercultural competence in the workforce including fewer human rights or equity complaints; more effective and efficient multicultural staff and team members; greater ability to meaningfully engage with stakeholders; attracting more creative, innovative staff members and volunteers; becoming more reflective of the diversity goals of the organization.

Intercultural competence forms a link between diversity and inclusion. Diversity focuses on the who: The mix of differences, and the impact of differences, measured by demographic analysis. For example, here in Thunder Bay, the official (conservative) estimate is that the Indigenous community makes up 15 percent of the population, but less than one percent of Thunder Bay Public Library staff members are Indigenous. So we have a diverse community but a homogenous public library staff. That is not a good combination.

Intercultural competence focuses on the how; i.e., how to make the cultural mix work, with a focus on the capacity to navigate cultural differences. Combining diversity and intercultural competence leads to inclusion, which focuses on the what; i.e., the experience, which is measured by outcomes. Inclusion happens when people are working together effectively and believe that their cultural experiences and differences are valued and engaged. Inclusion is leveraging differences in a way that increases contributions and opportunities for everyone.

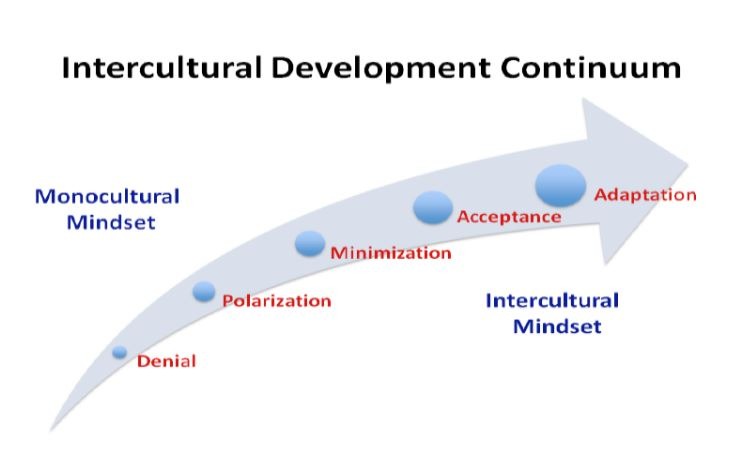

Intercultural competence can be thought of as being on a continuum that ranges from denial to adaptation.

Denial indicates a monocultural mindset in which cultural differences are either missed or ignored. Polarization suggests an assimilation mindset in which there is a level of discomfort with cultural differences, and these differences are judged. A minimization mindset tends to not hear or to de-emphasize difference in favour of universalism. An acceptance mindset deeply comprehends and understands difference. An adaption, or intercultural, mindset bridges differences; it is at this level that people, no matter what their cultural background, feel valued and engaged.

Every library will have workers who are positioned at different points on this intercultural competence continuum. Once individual library workers understand where they are positioned, they can start to develop their intercultural competence. A combination of cultural self-awareness, cultural other awareness and behavioural adaptation will enable workers to create a shift in their cultural perspective and their behaviour.

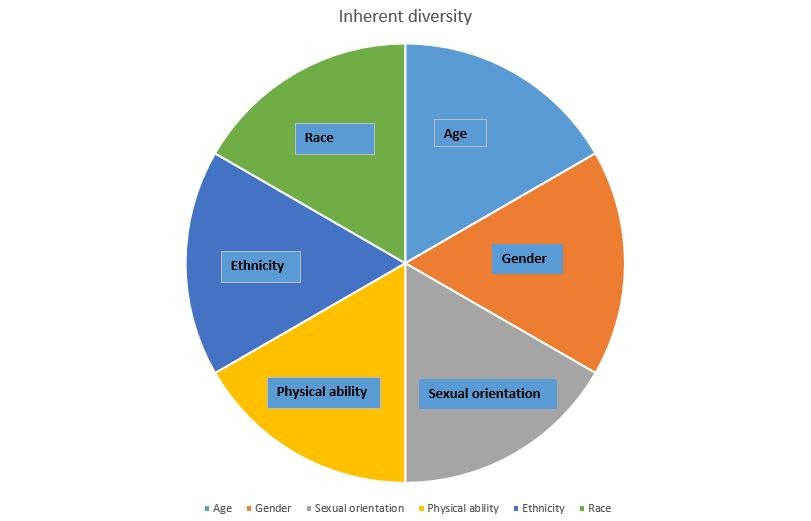

We all have a mixture of inherent, acquired and cognitive diversity that makes up our individual personalities. Inherent diversity includes factors such as age, gender, sexual orientation, physical ability, ethnicity and race.

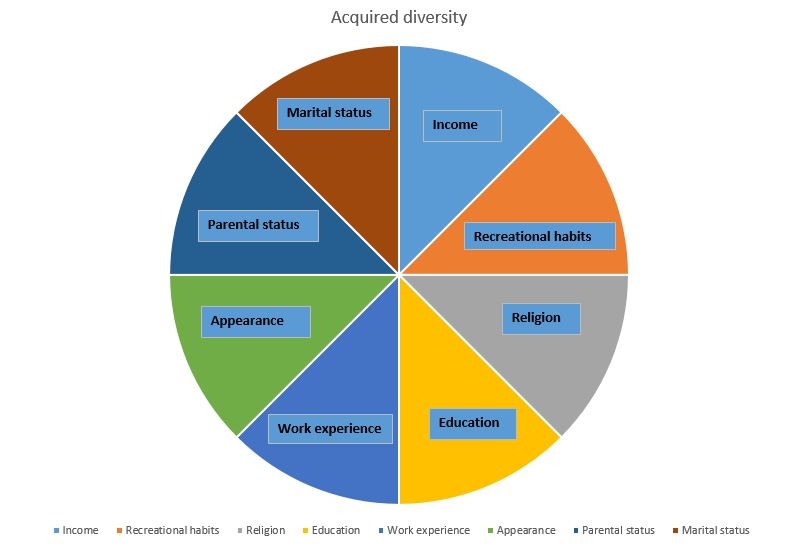

Acquired diversity encompasses geographic location, income, recreational habits, religion, educational background, work experience, appearance, parental status and marital status.

There are many intersections between the different types of diversity. For example, black working class women combine the inherent and the acquired diversity aspects of race, social class and gender. Cognitive diversity encompasses differences in perspective or in information processing styles; i.e., how individuals think about and engage with new, uncertain and complex situations.

The workplace creates some additional organizational dimensions such as functional level/classification, work content/field, division/department/unit/group, seniority, work location, union affiliation and management status. It is possible to create intercultural competence group profiles for different groups of workers, or for the whole organization. For example, the intercultural competence group profile of the board and administration might be different to that of librarians, technicians and assistants.

Intercultural conflicts arise because of misperception, communication misunderstanding, differences in goals, differences in values and needs, and misinterpretation of behaviour. By themselves, intercultural differences don’t necessarily lead to conflict, depending on how these differences are managed, and there is a range of intercultural styles. For example, the discussion style (direct and emotionally restrained), which predominates in North America and in Europe, is very different to the dynamic style (indirect and emotionally expressive), which is more common in the Middle East and in Asia. When under stress, experiencing emotional upset, or having a disagreement or a conflict, people tend to revert to their primary cultural programming, a reaction that could result in intercultural challenges in a work environment where staff members come from a range of geographic locations.

Intercultural competence forms part of the organizational cultural change that is required to transform traditional libraries into community-led and needs-based libraries. For this approach to be most effective, however, a whole organization approach should be adopted, with all board and staff members completing an intercultural competence program.

John Pateman is the CEO of the Thunder Bay Public Library. He is also the author of the Open for all? column in Open Shelf.