Learn about the benefits of constructing a multi-year internship from a MLIS student's perspective.

Reader, watcher, owner: Wholistic story-based library experiences

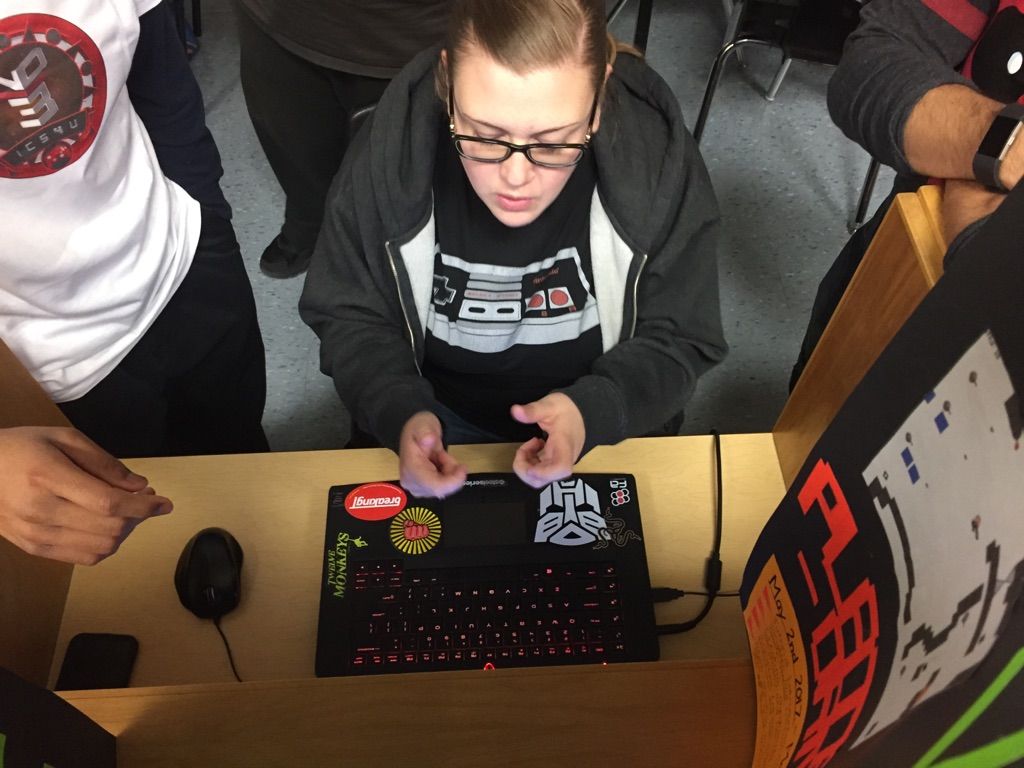

I spend a lot of my time reading books but also watching movies and, more often, watching other people play video games. Why? Because I’m a voracious collector of stories—different stories in different formats, but stories nonetheless.

But does the fact that I read and watch stories a lot mean also that I own these stories? I think so, even if my ownership is not the same as that of a given author or game developer. And some of this ownership is (and can be) created and supported for others through wholistic story-based library experiences provided in our play-based, remix and makerspace environments.

John Green (2010), a prolific teen author and YouTuber, thinks that the distinct difference between reading a story and playing through or watching a story can be summed up in one word: ownership.

“Because text-based stories give us something that video games and movies cannot: the ability to take ownership of a story.”

~ John Green, “The future of reading,” School Library Journal*

I’ve been so inspired by this idea that I’ve added Green’s words to the end of my email signature, a decision that in turn sparked a ferocious debate between me and a video game-loving colleague on what owning a story really entails.

And I’m glad to be having this conversation because I think that library spaces and practices create opportunities for us to make sense of the stories around us and become the creators and tellers of stories while also supporting our patrons as they do the same.

Take my experience, starting with the debate about owning video game stories …

My colleague argued that story ownership in a video game happens through the overlaid identity that comes from playing a character. This issue of identity is a defining difference between the two story-based experiences: while videogames have characters, just as books do, those characters are being manipulated by players into doing, instead of being interpreted through personal experiences. Players control the characters in video games and thus make the characters, in some ways, as extensions of themselves.

I was intrigued by this idea and it led me on a mission to understand the cognitive difference between reading and watching a story, specifically stories in books and video games. I discovered that there are similarities between the two experiences. Both are story-based and, to some extent, allow us to create a combined identity of ourselves and the characters. However, when we read, there are distinct communication and conceptual gaps between the written word and the reader and we must interpret words on the page, infer and then construct meaning as we proceed through the story.

My favourite example of this gap is getting teens to read the sentence “He owes me money” a number of times. Each time, I ask them to stress different words and add different punctuation, changes which alter the meaning of the sentence. Teens find it remarkable that such a short sentence can be interpreted in various ways. In essence, such interpretation fosters ownership.

Video games, even those supported by story lines, choice-making and textual narrative, don’t offer these same communication gaps. Players don’t have to interpret the story, or the characters, in a video game–they are creating the plot and developing characters through play action.

This debate—about what ownership means, how we acquire it and the implications of owning a story—has overflowed into ongoing conversations I’m having with other library workers around ownership in makerspaces, play-based learning, and remix culture. There seems to be some consensus that these spaces and paradigms allow participants to become interpreters and creators because everyone is free to remake, recreate and reinvent a story.

In turn, we recognize that through collections and programming, library staff can share the stories being created, interpreted, and manipulated and thus encourage others to build upon, reinvent and support the creation of even more new stories. Questions of copyright and intellectual rights inevitably bubble up from these negotiated spaces and discourses. But part of our work (and expertise), as library and information professionals, is to not only allow space for new ownerships to flourish but also constantly work to better define the terms of ownership to ensure all creators are protected.

Fanfiction writers are, by definition, part of remix culture as they take plotlines, characters, and settings from an established story and create deviant plotlines within the same realm. I asked a group of young writers with whom I was working to write a sentence or tagline for a well-known novel in a style or genre from pop culture. Here’s my favourite: Harry Potter: M.D. I’d love to see this medical drama!

As a result of rethinking and reworking existing stories, the group began asking questions about ownership, open content, meme generators, and whether “derivative” work (work we create based on or derived from the work of other creators) really counts as our own. I also seized the opportunity to introduce the Creative Common website and other sites with open access content.

So, the initial discussion between me and my video game-loving colleague has sparked in me a growing awareness of how I interact and interpret the world around me through stories, and how I share these experiences with others.. As important, the different ways we create spaces in which library patrons can become active readers, watchers and owners of stories is one that helps bridge the traditional idea of the library as a repository to the role of the library as a supporter of story-based experiences that can lead to new ideas of ownership and ways of creating.

* The article focused on the different ways we experience stories. Green writes that there is a fundamental difference in experiences “because text-based stories give us something that video games and movies cannot: the ability to take ownership of a story.”

Written by Kasey (Mallen) Walley

Photo credits: Kasey (Mallen) Whalley

Feature image: Rawpixel on Unsplash

Kasey (Mallen) Whalley has been working in and with libraries for over ten years. After completing her undergraduate degree in English from McMaster University, she immediately enrolled in and completed Seneca College’s Accelerated Library and information Technician program. She is currently employed as a Library and Information Technician with the Dufferin-Peel Catholic District School Board. She can be contacted at kaseywhalley [at] outlook.com.