Are there hard-and-fast rules for libraries engaged with LGBTQ+ communities? While there are areas where there should be clear guidance, there are others where context is more important.

Respecting anonymity through collection development

In the second article in this limited series of conversations, Amanda Wilk and John Vincent discuss readers’ advisory for LGBTQ+ people, and trends in publishing and accessibility of LGBTQ+ content in Canada and the United Kingdom.

Anonymity can be important to LGBTQ+ library customers who may not feel comfortable approaching a staff person to ask for assistance locating LGBTQ+ materials, in part due to long-standing and powerful social stigma.

In response, library staff on both sides of “the pond” have developed some processes to help patrons to find and access the content they want while respecting the need or desire for privacy. Some of these processes are as simple (and problematic) as using visible labels or stickers but others are more involved (and potentially less problematic), such as changing collections policies and purchasing procedures.

Cutting across strategies, however, is a commitment to ensuring that libraries spaces are safe and inclusive.

Throughout the series, John and Amanda will use the acronym LGBTQ+ to refer to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning and other identities within our community. We would like to acknowledge that other acronyms are also used, and that sexual and gender expressions are diverse and impossible to represent within the confines of five letters. For more information and terminology related to LGBTQ+ identities, the 519’s Glossary of Terms is a valuable resource.

We would love to engage with you, and welcome your comments and feedback below. Plus, once you’ve finishing reading this column, check out John Pateman’s interview with John V. in Open for all?

Amanda Wilk (A.W.)

In response to the need or desire for anonymity, some Canadian libraries label LGBTQ+ content (particularly for children and youth) with rainbow stickers to make them more visible in the collection.

This is not a strategy that I personally support, nor is it one that the American Library Association stands behind, largely because identifying books with LGBTQ+ labels may prevent library users from accessing them for fear of being outed. We need to find other ways to promote LGBTQ+ content in our collection, so that in promoting titles we are not simultaneously alienating readers from books that they would like to access.

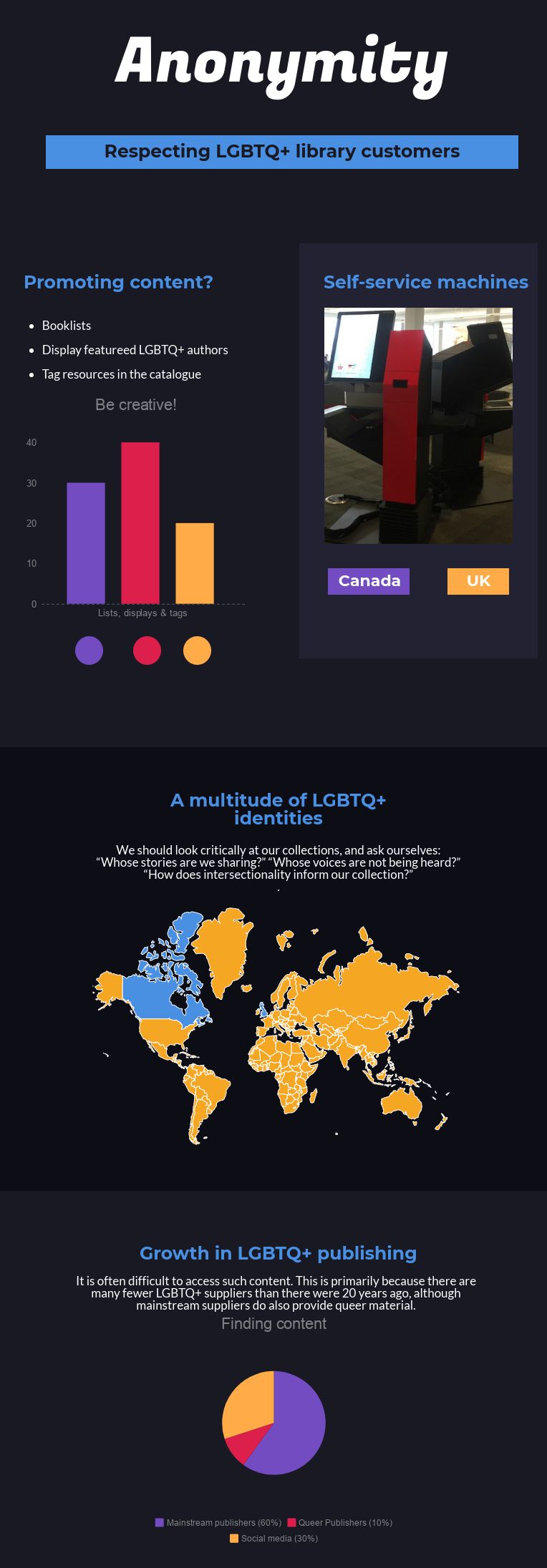

Libraries might consider creating LGBTQ+ specific book lists, and tagging resources in their catalogue to make them more accessible to customers searching for queer content. It is also important that libraries include LGBTQ+ content in all forms of displays and readers’ advisory.

Creating a display for Mother’s Day? Look at including titles like Stella Brings the Family by Miriam B. Schiffer. Celebrating Poetry Month? Be sure to include the work of LGBTQ+ poets (there are many! A Place Called No Homeland by Kai Cheng Thom is one of my recent favourites).

Because anonymity can be a priority to LGBTQ+ library customers, I think that providing access to self-checkout machines, which allow them to sign-out library materials without the assistance of a staff person, is important. However, many readers might be unable to feel safe taking LGBTQ+ items home, or have concerns about having a record of LGBTQ+ content on their library account. As a result, LGBTQ+ items might circulate less frequently than other items in a collection even though they may be accessed just as much.

In response to this, libraries might consider having different collection maintenance guidelines for LGBTQ+ non-fiction, which can be an incredible window into what is possible for LGBTQ+ people. Ensuring these titles aren’t weeded just because they do not have high circulation stats will allow LGBTQ+ customers to continue accessing these materials inside library walls.

Do you see similarities in the United Kingdom?

John Vincent (J.V.)

Yes and no!

I completely agree about anonymity (and this has always been an issue around having separate, highlighted LGBTQ+ collections). There is some evidence here that the introduction of self-service issuing of library materials has had a positive effect: it may be apocryphal, but I remember hearing about a student who was so glad that there was self-issue in their library. The library staff were friends with their mother, and they were not sure that the staff member might not mention something in conversation.

I also agree that we need to find different ways of promoting LGBTQ+ materials: book lists, displays, the inclusion of LGBTQ+ material into other displays and events (to celebrate Black History Month, for example), and tagging material in the catalogue are all positive solutions.

Some libraries do still have separate LGBTQ+ collections, and there would be a problem here for many if the books weren’t labelled (e.g., with a rainbow sticker). Many staff, especially newer and/or casually-employed staff, would not know whether titles were LGBTQ+ or not, so stickers are valuable because they help us keep our collections topped-up.

A.W.

Content—collection development—is critical to good library service. More and more in recent years, I have seen a rise in the diversity of LGBTQ+ content available in Canada. There is work to be done, but stories that reflect a multitude of LGBTQ+ identities and experiences are becoming easier to find—and purchase—these days.

With this in mind, having a collection that reflects the diversity of LGBTQ+ people and their identities cannot be understated. We should look critically at our collections, and ask ourselves: “Whose stories are we sharing?” “Whose voices are not being heard?” “How does intersectionality inform our collection?”

Not only do we need to ensure we are including vast experiences of queerness, but we also must ensure that we are telling diverse stories that reflect different cultures, ethnicities, ages, abilities, etc. Working directly with community is one strategy to help develop a comprehensive collection. In addition, I use many resources to inform collection development, they include:

- Over the Rainbow Books: a booklist from the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Round Table of the American Library Association

- Lambda Literary: the largest LGBTQ+ literary community in the world

- Rainbow Books: a comprehensive resource on LGBTQIA+ titles for readers from 0-18 created by the Rainbow Book List Committee of the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Round Table of the American Library Association

- Stonewall Book Awards: the first and most enduring award for LGBTQIA+ titles for young readers

- Staying current with Independent Presses like Arsenal Pulp Press, a Canadian independent book publishing company based in Vancouver, British Columbia

- Following blogs like Casey the Canadian Lesbrarian

- Looking to LGBTQ+ bookstores like Toronto’s Glad Day Bookshop, the world’s oldest LGBTQ+ bookshop

Have you seen a similar increase in the breadth of stories being told and readily available in the United Kingdom? What resources are available there to locate LGBTQ+ content?

J.V.

I think “yes and no” is going to be my default reply this time round!

Yes, there is definitely a similar growth in LGBTQ+ publishing here too, but, for libraries, it is often difficult to access such content. This is primarily because there are many fewer LGBTQ+ suppliers than there were 20 years ago, although mainstream suppliers do also provide queer material, obviously. There is also a number of “radical” bookshops which may well have queer titles in stock, but many library services are prevented from purchasing from these suppliers because of the contracts they have entered into with large supply chains.

However, many public libraries here have switched to supplier selection (i.e., they provide a spec for what they require, and mainstream suppliers then provide material to match the spec). In positive terms, this means that library staff do not have to spend time ordering obvious bestsellers, but the process also means that individual library staff may become de-skilled because they aren’t seeing and evaluating many books before they are delivered to their library. Plus, many may also have limited opportunities to order individual specific titles or to visit a queer supplier.

A handful of library suppliers dominate much of the mainstream supply—they, in turn, deal primarily with larger, more established publishers. As a result, it is also difficult to find out about and purchase materials from smaller and/or non-mainstream publishers. Some library services, however, do still purchase from a smaller supplier, Bookscan Library Services, that supplies LGBT stock.

In addition, public libraries here have been subject to major budget reductions since the banking crisis of 2008 (and the strong austerity line being held by coalition and Conservative-led governments since 2010), and this is meaning that fewer library materials are being purchased (and there are, generally, fewer staff to promote the stock if it is purchased).

There has been considerable research here recently into the availability of queer materials for children and young people (more about that in a moment). At the same time, there are growing criticisms of the lack of diversity in children’s/young people’s books. Following considerable debate about the relative lack of Black and minority ethnic representation in children’s books, for example, the trade magazine, The Bookseller has just reported that two key children’s book organisations are to review ethnic representation in children’s literature, and there are parallel concerns about the representation of the full range of queer characters.

My colleague, Elizabeth L. Chapman (Associate Lecturer, Department of Education, Childhood and Inclusion, Sheffield Hallam University), has researched and written about the provision of queer books and materials for children and young people. For her PhD thesis, she looked at Provision of LGBT-related fiction to children and young people in English public libraries. Elizabeth has since shared her ideas with library professionals through:

- A list of publications, LGBTQ* fiction for children & young people, in 2015.

- A key blogpost for The Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals (CILIP): “Improving LGBTQ* provision in your library: why and how to do it,” which includes a link to a resources list that highlights just how limited the sources in the U.K. are in that it includes only two:

- Gay’s the Word bookshop

- Letterbox Library, a supplier of diverse materials for children and young people

Publishers and booksellers promote queer books, especially to tie into LGBT History Month (February) and local Pride celebrations. But otherwise, it is quite difficult to locate titles unless you are “in the know,” and there is a real danger that library suppliers, booksellers, and some library staff, will end up seeing the provision of queer materials as “niche.”

Acknowledgement: I am very grateful to Chris Dobb (Development Librarian, Greenwich Leisure Limited) for helping me with the section on library supply.

References

Mental health care for people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and (or) queer

Amanda Wilk is a branch manager at Kitchener Public Library. She can be reached at amanda.wilk [at] kpl.org.

John Vincent is the networker for The Network – tackling social exclusion, based in the U.K. John can be reached at john [at] nadder.org.uk.