This month, Trevor Deck walks us through the library’s collection development mandates, scope and goals.

Bienvenue à la Bibliotheque: Anglophone and francophone perspectives on French-language services (Part 2)

By: Katherine van der Linden and Claire Dionne

This article is the second in a three-part series exploring the challenges of offering French-language library services in a majorly anglophone environment.

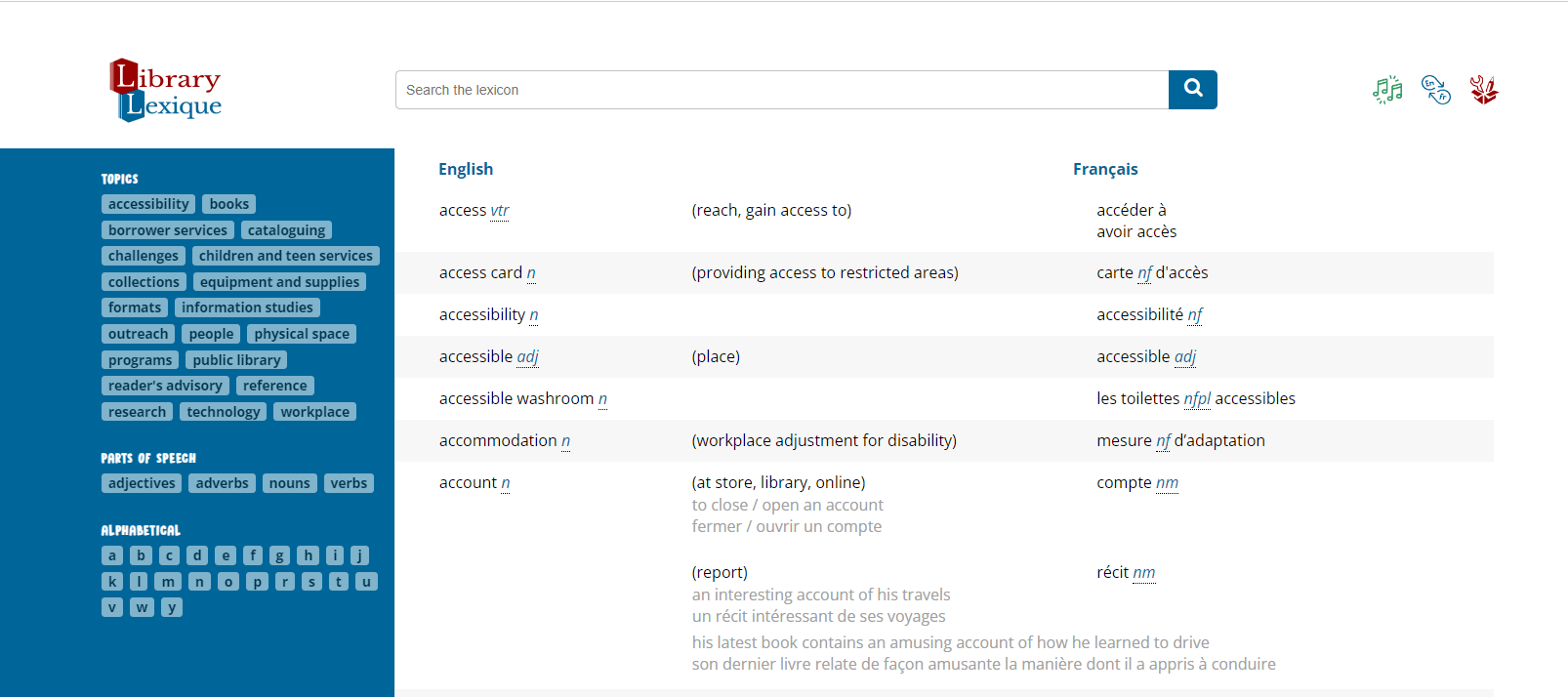

Working in a bilingual environment can offer a window into another culture and increase one’s depth of experience. A rich vocabulary is particularly valuable in permitting free-flowing expression between the languages. As discussed in the first article in this series, gaining this level of linguistic mastery can be an onerous process. The founders of Library Lexique created its English-to-French to bridge the gap for library workers struggling to travel between the two languages in their professional life. Here, we will discuss the process of creating the dictionary and the many challenging editorial decisions faced along the way.

Having a clear target audience is crucial to the success of a dictionary, as this drives all future decisions around the range of words to be included, the level of detail in the descriptions, and where to write examples. The Library Lexique dictionary was designed for native francophones and intermediate to advanced French speakers, focusing on public service in public libraries. As laypeople in the field of translation, we felt it was safest to concentrate our efforts on the language area in which we felt most confident and had a network of others to draw on for support.

Once the project audience was determined, we considered what kinds of terms would be most valuable to them. The original list contained many words which were not specific to libraries, such as office supplies (for example, stapler, binder, paperclip), technology (for example, web browser, mouse) and standard business terms (for example, CV, educational background). Many of these were widely available elsewhere.

The difficulty arose in establishing clear criteria for what belonged and what did not. On the one hand, our anticipated target audience included intermediate to advanced learners who would benefit from some words not exclusive to the library context. On the other hand, we were concerned that native francophones might be discouraged if the domain-specific terms were buried amongst widespread words. We also had to weigh the value of including words that could easily be found elsewhere against the amount of time the authors had available to devote to this personal project.

Ultimately, we decided to include the generic terms that were less frequently used and most relevant to work in public libraries (for example, construction paper and personal information). We moved prevalent generic words (for example, computer mouse, stapler) to vocabulary lists, assuming they would be most useful as a study tool. These lists are already available on Library Lexique in the Flashcards section.

The next step was to choose the English words that would become the dictionary entries. This was a process of weeding to remove the non-library-specific comments and one of development, to increase coverage in our chosen subject areas. To assist in the development, we consulted numerous glossaries in English and French. The list of resources consulted is available on the Library glossaries and bilingual dictionaries page of Library Lexique.

Once a term was selected in the dictionary, a translation had to be found or created. This was an often complex and laborious process, as we were creating the dictionary expressly because many library terms needed readily available translations. We had to face the same challenge we were trying to address. Words often cannot be translated one-to-one due to the connotations, meanings, and references they carry in both languages. A certain image or idea is called to mind when we hear a word. The translation must convey a similar meaning, sense, and image to the original language. Additionally, the target language’s grammar rules must also be considered, as well as the cultural context.

The individual entries began with research in standard bilingual dictionaries and glossaries, to see if a translation already existed. We used multiple sources to gather information on the terms and their translation. We would begin with bilingual language dictionaries and resources, such as Termium Plus, Le grand dictionnaire terminologique, and Larousse. When the term did not appear in any of these resources, we investigated websites with official and reliable English and French versions, such as those from the Government of Canada, bilingual libraries, and occasionally business websites (e.g., Staples/Bureau en gros). If this failed, we would turn to French-language sources, including francophone libraries, mostly from Québec, or the website of the École de bibliothéconomie et des sciences de l’information to look for a word or phrase expressing the desired concept (for example, look for pre-literacy program titles to find equivalents for “story time”), and open source journals, such as Érudit. If even this failed, we resorted to blog posts, colleagues, or any other resource where we might find any lead to how this term could be translated. Throughout, we checked for consistency between the resources and frequency of use.

The most challenging entries generally contained elements of one or more of the following:

1. Wordplay

The reliance on playing with the sense and sounds of a language makes wordplay inherently tricky to translate. A literal meaning can be found, which risks losing the playful sense of the original expression. Conversely, an overly clever linguistic equivalent in the target language may need to be more concise for the reader to understand. In addition, wordplay is typically used operationally, meaning that they rarely appear in the French-language official documents and website content that we used as research material.

For example: “book tasting,” “book talk,” “shelf-talker,” or “chick lit.”

2. Many different accepted translations for a single concept

Some terms had multiple suggestions or options for translation in French, many valid and popular. For a dictionary to be helpful, it should be manageable for the reader with many translations for a single idea, mainly when the options are almost identical. This selection process inherently results in promoting specific terms over others. As non-experts in the language field, we were hesitant to take such a role in steering the use of the language. We needed to be cautious and rely on evidence of usage from reliable sources in selecting which translations to include

Example 1: The term “makerspace” is translated by different organizations as “laboratoire ouvert,” “fablab,” “espaces de fabrication collectifs,” “espace de création,” “médialab,” and “laboratoire de création.”

Example 2: The term “storytime” is translated in texts and by libraries as “heure du conte,” “heure de conte”, and “heure de contes.”

3. Untranslatable words

In the most challenging cases, a concept that could be expressed using a single term in English could not be translated the same way in different contexts in French.

For example, “outreach” is an all-purpose term in English. It is used to offer programming outside library walls, set up a booth at a local event, and attend a local community association meeting. In French, it is more common to describe the location of an activity to communicate the idea that it was being done in the English sense of an “outreach.” Thus, “an outreach” at a school might be translated as “une heure du conte dans une école” while the “outreach statistics” might be described as “les statistiques des services hors les murs.”

If we had doubts about a proposed translation, we verified it in French dictionaries and language resources to ensure it did not violate any rules, was not an Anglicism, and that it meant what we thought it did. We often double-checked official definitions by Googling them and searching them on French library websites to ensure they were actually in current usage. In a few cases, additional research was required to confirm them. For example, the verb “to shelve” in English can be translated in French as “ranger” or “classer,” and the difference between them is subtle to the point that they are both completely valid options.

When our research uncovered many different options, we carefully considered which ones to include. We preferred terms that were commonly used (for example, “pantin” is a valid term for a specific kind of puppet, but the more general “marionnette” is far more popular). We discarded terms that were not official French, even if they were commonly used (for example, “ruban adhésif” was in, while the Anglicism “tape” was out). We also prioritized Canadian translations, as opposed to terms more often used in Parisian French (“documentaire” is preferred to “non-fiction”).

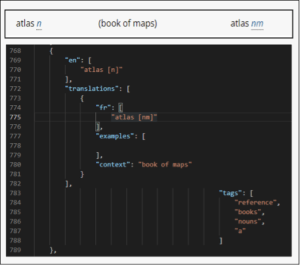

Finally, we added context to the terms by providing a scope note and sentence examples to convey how this term should be used and bring clarity. This is especially useful in cases where one term may have different meanings and require other translations depending on the context (for example, outreach).

Creating the dictionary in Library Lexique has deepened our appreciation of the power of language while highlighting the many pitfalls that litter the road to meaningful translation. Ultimately, we are proud to offer our friends and colleagues this unique tool. The success of the project has encouraged us to continue its development. We invite you to contact us at librarylexique@gmail.com if you have a term suggestion to add. Please look for the third and final article in this series in the upcoming Winter 2024 edition, where we will discuss some aspects of bilingual French-English programming for young children.

Which library terms do you have the most trouble translating? Share in the comments below!

Katherine and Claire can be reached at librarylexique@gmail.com.