Learn about the benefits of constructing a multi-year internship from a MLIS student's perspective.

Taking responsibility: A single source may be CRAP when talking about governance

By Andrew Gemmell and Martha Attridge Bufton

“Canada found a cunning way to abrogate its fiduciary duty,

adopting the inherent right of self-government (rationale).”

~ Catherine Twinn

In the second and final installment of this article, Martha (Attridge Bufton) and Andrew (Gemmell) look at the question of “single source” arguments.

In her editorial on the accountability of Indigenous communities, Diane Francis relies principally on the opinions of a single source, Indigenous lawyer and activist Catherine Twinn. As Indigenous scholar Kahente Horn-Miller argued in the last installment, the question of governance is complex, so clearly, any discussion of accountability within the context of Indigenous Peoples and state relationships needs to be nuanced and multi-vocal. Especially since the Indian Act represents simultaneously the paternalistic and colonial control of Indigenous lives, families, and societies, and the enshrinement of Indigenous special status in the Canadian constitutional order.

This time, Andrew and Martha start with their “information seeking” process and present the “CRAP” test, a well-known method for thinking critically about online information that can work across different types of sources (e.g., magazine articles, blogs and newspapers). Then they move on to unpacking Diane Francis and Catherine Twinn’s thinking by contextualizing their ideas within wider debates in Aboriginal law and Indigenous critical theory.

Part I: Using CRAP to evaluate online information

Risqué—that’s how academic librarians Molly Beestrum and Kenneth Orenic describe the CRAP test. And certainly every time I (Martha) introduce this methodology for evaluating online information to students there is (at the very least) a gentle twitter that ripples through the classroom. Maybe librarians aren’t supposed to say crap.

In any case, I do and often, because this acronym has proven to be a very useful tool for getting beginning researchers to think about the quality of the information that they are using in their own academic work.

Now it can definitely be argued that university students (either undergraduates or graduate students) are not beginners when it comes to searching for and finding information online. After all, they are spending lots of time in cyberspace (often doing a great deal of their school work via their mobile devices) so they can clearly navigate the web. But “search and find” activities do not mean that users can also critically evaluate the quality of the information they find. And I always assume that the CRAP test can, at the very least, remind more seasoned searchers to really stop and think about their sources.

So what does CRAP stand for?

C is for currency of information and prompts users to think about how up-to-date (or out-of-date) information is. For example, when was a website last updated? And do regular updates matter?

C is for currency of information and prompts users to think about how up-to-date (or out-of-date) information is. For example, when was a website last updated? And do regular updates matter?

R is for reliability or the trustworthiness of information. For example, is an academic article published in a peer-reviewed journal and does this matter?

A is for authority which really encourages users to think about who or what (i.e., an individual organization) is creating the content. Why is an expert an expert? What are their credentials?

P is for point-of-view, which translates into asking questions about an author’s reasons for publishing. Do they have a clear bias? Are they advocating for a particular position or take on an issue?

The CRAP test has been around since the early 2000s and has even been modified to become CRAAP and include another A for accuracy. And, of course, evidence and facts do matter.

As a basic framework for thinking about the information we find, I think that CRAP is good as a way [of at least starting] to curate the vast amount of information that we can find, both online and offline (i.e. in print). In fact, in some ways the peer review process reflects similar thinking as readers look to establish the “publishability” of academic research. The “best” articles are current (at least in theory—as an historian I am okay with “old” information), trustworthy in their methods and conclusions, authoritative and explicit in their analytic perspective.

So what happens when we apply our CRAP test to Diane Francis’s editorial and her use of a single source to make the argument that the federal government must enforce Indigenous accountability as set out in the Indian Act?

Well, let’s just say that a single source might win the CRAP battle but lose the governance war. At the very least, a single voice cannot speak for all Indigenous Peoples.

Part II: Thinking critically about media

“Ironically, the leaders of the country’s 632 First Nations aren’t required to, and often do not, consult with their own band members. This is because Canada has gradually ceded its oversight powers to band chiefs and councils, without checks and balances, or any semblance of accountability—a devolution of power that has worsened since Prime Minister Justin Trudeau took power in 2015, according to Indigenous lawyer and activist Catherine Twinn.”

The above quote should make a careful reader pause. Given the diversity of First Nations in Canada, how can one make such sweeping and unsubstantiated claims as to the irresponsibility and untrustworthiness of Aboriginal leaders (as if Canadian politicians are so categorically transparent and trustworthy), and then go on to reference only one source? This reliance on a one source is an indication that author Diane Francis is writing from an ideological position; she is offering an editorial opinion written to score points rather than a balanced consideration of the topic at hand.

Francis’s ideological bent is clear by the tone and substance of her editorial, which leans heavily on racial stereotypes and broad generalizations. Most problematically, perhaps, are the taken-for-granted premises: the Canadian state has a fiduciary duty to its Indigenous peoples, and this is an uncontroversial relationship. Rather, this is one of the most hotly debated relationships in the Canadian context. Diane Francis is writing from an ideological position; she offers an editorial opinion written to score points.

On one hand, the question of fiduciary duty is meant to protect Indigenous peoples from Crown misconduct, so framing the relationship as Francis does is one-sided. But even according to a more robust understanding, the fiduciary principle is not uncontroversial. Aboriginal law expert Jamie Dickson, in his 2015 book The Honour and Dishonour of the Crown: Making Sense of Aboriginal Law in Canada, suggests that recent Supreme Court jurisprudence has repositioned this relationship in ways that are “entirely redundant and of no ongoing practical utility,” “leaving much confusion and doctrinal overlap”. Dickson argues against the Court’s sui generis interpretation, preferring a return to “conventional fiduciary duties” as they are understood within contract law.

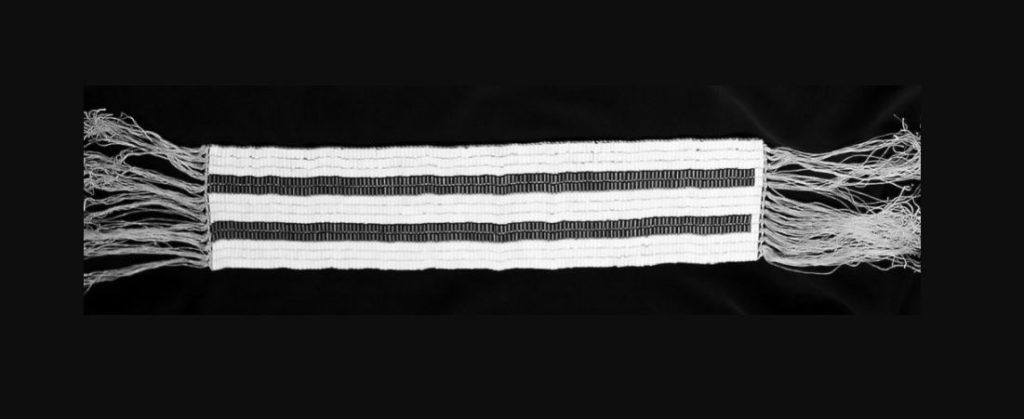

Other scholars, like Anishinaabe jurist Aaron Mills, are much more critical of fiduciary duty and the transposition of contract law onto federal-Indigenous relations. As he wrote in 2017: “Because of their common commitment to (1) contract as the source of our shared political community and (2) their reduction of treaties to minor contracts within the prior and unquestioned social contract, I’ll argue that both the Crown and the Supreme Court are structurally committed to violence”. Critics of the fiduciary relationship, of which there are many (foremost among whom is perhaps John Borrows), point to the Guswentha or Two Row Wampum, or the Covenant Chain, or the principles consensually established at the Treaty of Niagara, 1764, as a better model of nation-to-nation relations. Francis makes no reference to this controversy, however. Instead, using as her single source, an Indigenous lawyer named Catherine Twinn, Francis argues that Aboriginal politicians are irresponsible and untrustworthy, and that Indigenous rights and communal Aboriginal title should be abolished.

The reader needs further background to understand this point. Aboriginal title to land is a communal right, and according to Canadian law, First Nations land cannot be sold or taxed as it is held collectively by the Indigenous community. From the perspective of free-market neoliberalism, this is a problem, because communal rights stand in the way of unrestrained corporate natural resource exploitation. Although Diane Francis is writing as a journalist, and claims to be concerned first and foremost with human rights, it should be noted that she is an insider to extractivism—she served as a director to two mining companies, Aurizon Mines and Lake Shore Gold.

In support of her argument advocating the abolition of Indigenous rights and Aboriginal title, Francis turns to Catherine Twinn. This choice is illuminating. Twinn’s late husband, Walter Twinn, was Chief of the Sawridge First Nation from 1966, which is about the time that oil was discovered on the Sawridge reserve. His work with oil companies earned him a Progressive Conservative Senate appointment in 1990, which he held until his passing in 1997. This extractivist connection between Francis and Twinn is not incidental. In fact, it is the entire point of her piece: Aboriginal title and Indigenous rights, which are constitutionally protected, get in the way of corporate exploitation and so should be abolished. As the astute reader will know, this sort of full-throated defence of the resource industry is not out of character for the Financial Post (rather, is its raison d’etre).

The heavy lifting done by Twinn in this piece as the solitary voice of Indigenous peoples is remarkable (one may note that in subsequent editorials, Francis searches out another source to bolster Twinn’s voice). So is the fact that Francis does not make any effort to mention the controversies surrounding the problematic fiduciary relationship she seems to want to defend. Add to this that the special status Francis argues should be eliminated is a species of rights protected by the Canadian Constitution and by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and we have a text that arguably does not stand up to the CRAP test.

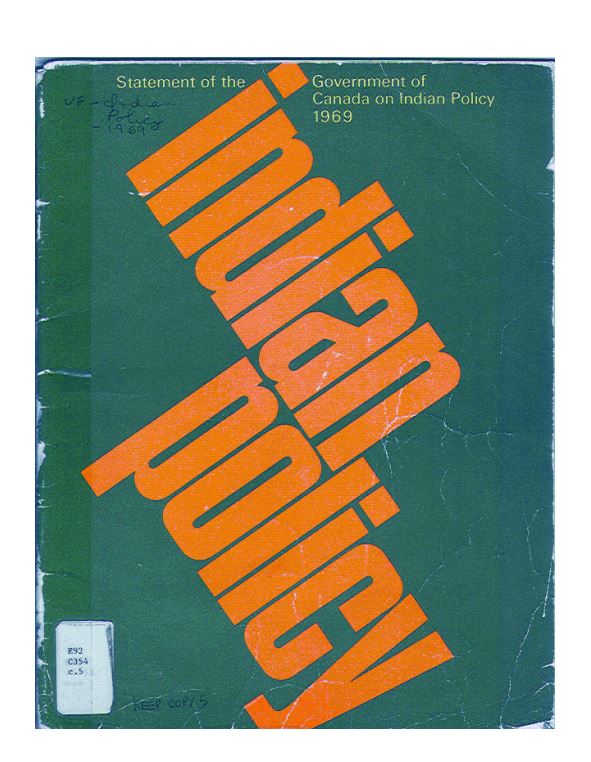

Notably, as many familiar with modern Aboriginal politics in Canada will immediately recognize, Francis’s arguments are a rehashing of the proposals tabled by the failed White Paper, 1969.

Put forward by Prime Minister Trudeau and Jean Chrétien, his Minister of the Department of Indian and Northern Development, this notorious policy document had six central points:

- Repeal the Indian Act and special rights;

- Devolve federal responsibilities to the provinces;

- Encourage integration over assimilation or the reserve system;

- Establish interim funding;

- Terminate any remaining treaty obligations with Commission oversight;

- Transfer reserves to Indigenous band councils, removing protections against taxation and sale.

At the time, the White Paper was met with indignation and hostility, and Trudeau was forced to withdraw it with his tail between his legs. These policies aimed to open up lands protected under Aboriginal title for unconstrained resource extraction, and Francis makes her argument in a roundabout way, by attacking the Liberal government as asleep at the wheel, Indigenous leaders as unaccountable and corrupt, and constitutionally-protected Indigenous rights as undermining universal human rights.

As an additional (and alternative) source to the opinions of Catherine Twinn, consult Indigenous scholarship on the topic. For example:

- Work recently compiled by John Borrows (Resurgence and Reconciliation: Indigenous-Settler Relations and Earth Teachings, edited with James Tully and Michael Asch, 2018)

- The Right Relationship: Reimagining the Implementation of Historical Treaties, edited with Michael Coyle, 2017

Recently published research from the Yellowhead Institute. Their special reports on this topic are available online: Canada’s Emerging Indigenous Rights Framework: A Critical Analysis or The Rise of the First Nations Land Management Regime in Canada: A Critical Analysis.

In this presentation, Indigenous scholar Aaron Mills shares some of his thinking of Indigenous governance and Indigenous-Crown relations.

Further reading

Mills, A., Drake, K., & Muthusamipillai, T. (2017). An Anishinaabe Constitutional Order. Osgoode Digital Commons, articles & book chapters. 2695. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/scholarly_works/2695

Andrew Gemmell (MA Philosophy, NSSR; PhD student, SICS and Institute of Political Economy, Carleton University) brings a background in philosophy and critical theory to his work on Indigenous-newcomer histories and institutions and settler colonialism in the Canadian context, which focuses on the formal structures of settler colonial responsibility and accountability.

Martha Attridge Bufton (MA, MLIS, Graduate Certificate in TBDL) is the Open Shelf editor-in-chief. Martha is the Interdisciplinary Studies Librarian in Research Support Services at the Carleton University Library and her research interests include game-based learning and culturally responsive pedagogy. She can be reached at martha.attridgebufton [at] carleton.ca.