Learn about the benefits of constructing a multi-year internship from a MLIS student's perspective.

Weeding as an anti-racist practice: A conversation with Dr. Monica Eileen Patterson

By Martha Attridge Bufton and Monica Eileen Patterson

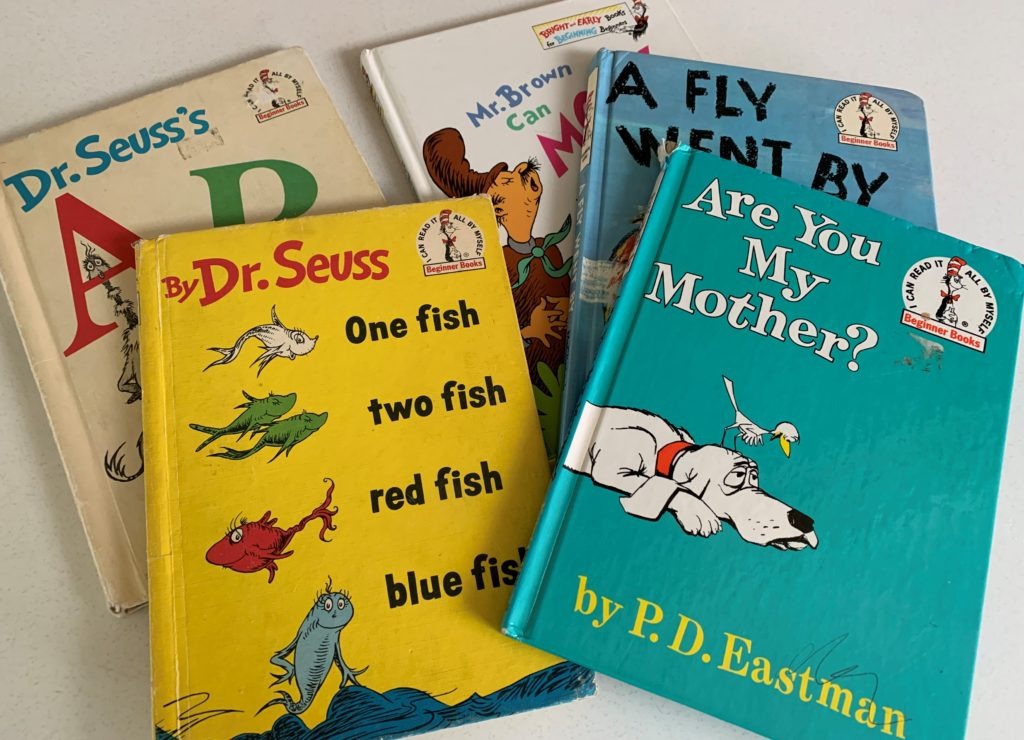

Collection management is an important component of library work in part because the materials on our shelves reflect our deepest cultural beliefs and experiences. So, decisions about what to keep and what to discard are critical to our commitment to equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) in our libraries, i.e., to our commitment to anti-discriminatory practices. Talking about EDI issues—with each other as well as our broader communities—helps us make good decisions when managing our holdings. Take Dr. Seuss…as I am learning from my colleague, Dr. Monica Eileen Patterson, withdrawing some of his books from publication is the right thing to do because children should not be exposed to racist imagery and stereotypes. And yet, there may be times when we might still need access to some of these texts in order to understand how racism operates in our communities.

I was very lucky growing up: I got to read a lot. My parents were both teachers and were passionate about making sure that my two sisters and I learned to love reading. As a result, they read to us aloud (from picture books to biographies such as Born Free) and then, when we started to read to ourselves, they made sure we had a good supply of books to choose from.

I am sure that we read widely and that there was little overt censorship (although my mother cringed a bit as I consumed book after book in the Nancy Drew series). Interestingly, I am not sure that we read a lot of Dr. Seuss—except The Cat in the Hat.

And yet, somewhere along the line, I became aware of And to think that I saw it on Mulberry Street, a book (one of six) that the folks at Dr. Seuss Enterprises have decided to pull from publication because it contains racist imagery.

I wasn’t aware of this decision until my colleague, Dr. Monica Eileen Patterson, sent me a link to the recent opinion piece that she wrote for The Conversation: From erasure to recategorizing: What we should do with Dr. Seuss books.

Monica, an historical anthropologist, is an associate professor in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Carleton University, where she teaches in the Institute of Interdisciplinary Studies and is also the assistant director of Curatorial Studies in Carleton’s Institute for the Comparative Study of Literature, Art and Culture. We teach together and are currently part of the team of faculty in the Childhood and Youth Studies program who are strategically building a collection of contemporary children’s literature that can be used in teaching and research at Carleton.

Partly because of this collection development work and because I am an historian too, I am very interested in Monica’s thinking on this topic, i.e., collection management and how “deselecting” intersects with concerns about how and why we teach history. From her perspective, we need to “retire racist texts” from children’s lit collections as part of our anti-racist practice and yet, we still need to engage with these texts in some context in order to “interrupt racist legacies.”

Take a listen to the following storycast (Part I and Part II), where Monica and I talk a bit more about this topic and she explains why it’s important to think critically about children’s literature, for both young children and university students alike. Weeding can, in fact, be an anti-racist practice.

In Part I, Monica talks about the decision to cease publication of six Dr. Seuss books and how she introduces and frames difficult historical texts to her students.

In Part II, Monica talks about one approach that libraries might take to managing problematic materials. She proposes removing such materials from circulation and tagging them for users as one solution because she believes that there are precedents elsewhere for making such a decision. For example, Americans are finally seeing movement in the South to remove confederate flags from state flags and public display, and confederate monuments from public spaces.

Monica understands that some critics have decried these moves as an erasure of history—this misunderstands “history”—particularly in its public forms of representation, which is always an assemblage of erasures. However, certain objects are active and galvanizing symbols of hate (e.g., confederate flags, swastikas, and racist caricatures) that convey powerful messages promoting ideologies of white supremacy, invoking histories of violence and oppression, and perpetuating that oppression in the present. Rather than subjecting the targets of such violence and symbolism (or anyone) to those messages, she proposes that libraries, archives and museums find strategies such as tagging to provide access to such materials in safer ways.

She also recommends two books that she believes are good examples of anti-racists children’s literature.

Original scores by Diego Guzman.

Martha Attridge Bufton (MA, MLIS, Graduate Certificate in TBDL) is the former Open Shelf editor-in-chief and a member of Editors Canada. Martha is the Interdisciplinary Studies Librarian in Research Support Services at the Carleton University Library and her research interests include game-based learning and culturally responsive pedagogy. She can be reached at martha.attridgebufton [at] carleton.ca.

Monica Eileen Patterson is Assistant Director of Curatorial Studies in the Institute for the Comparative Study of Literature, Art, and Culture, and Associate Professor in the Institute of Interdisciplinary Studies at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada. She earned her Ph.D. in Anthropology and History and a certificate in Museum Studies from the University of Michigan.