I am intrigued with the work of fabulous secondary teacher librarian, Jonelle St. Aubyn. Her practice is both familiar and innovative.

Making room for diverse voices in our schools

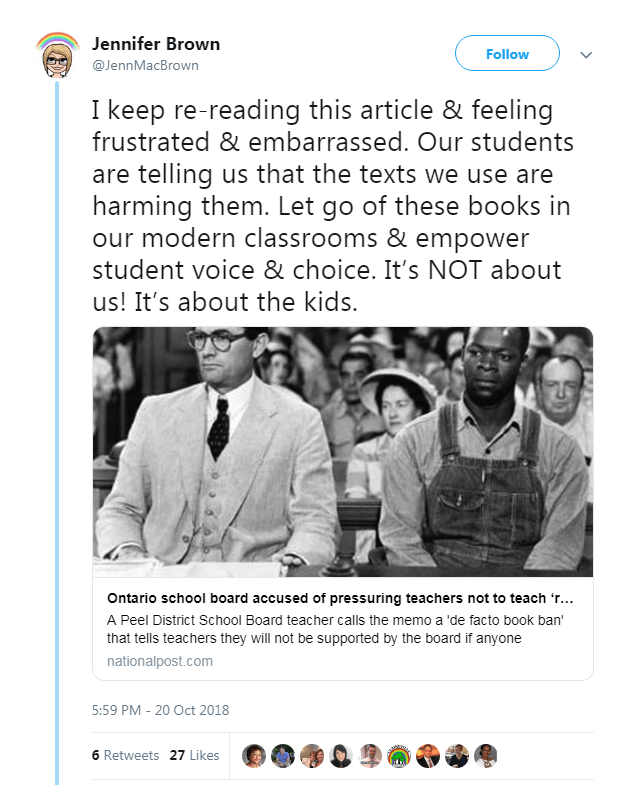

It can be easy to say that our school library learning commons is a safe space, grounded in the principles of equity, social justice and human rights. The reality is that simply saying something out loud does not make it true. Nothing brings this to light more than the recent media and social media coverage of the use of To kill a mockingbird in secondary English classrooms. This conversation around language, race, student voice and the texts we value has fueled a wide range of public responses. In my opinion, the dialogue has emboldened many to reveal ideas that are, at best, completely out of touch, and, at worst, grounded in white privilege and fragility.

The media coverage, links to some of which appear below, has predominantly focused its energy on a memo from the Peel District School Board that was shared with secondary English teachers around the importance of reflective and thoughtful decision making when selecting required texts for students in their care. Rethinking the use, and definition of “classic” texts, and ensuring a critical lens of anti-oppression is implemented when making these decisions is essential to creating modern and culturally responsive classrooms. For example:

- CBC Radio, Ottawa Morning: How to Kill A Mockingbird racist?

- National Post: Ontario school board accused of pressuring teachers not to teach ‘racist’ To Kill a Mockingbird

- CBC News: Peel District School Board takes new approach to teaching To Kill a Mockingbird

- Globe and Mail: No, To Kill a Mockingbird shouldn’t be taught in 2018

Not being a member of the secondary panel I cannot speak to the details around the memo directly, and would never presume to do so. I can say that my understanding is that one of the goals was to address the ongoing concerns from students, families and staff who experience pain and discomfort when required to read, listen to, and teach outdated content such as that in the 58 year old American novel by Harper Lee.

When our Black students, their parents, and staff tell us that a book we use is causing them harm, we must listen to and believe what is being shared.

If we accept the idea that language evolves over time as societal norms change and develop, we must accept that this evolution comes about, at least in part, because members of oppressed groups are impacted negatively, and harmed by its use. When our Black students, their parents, and staff tell us that a book we use is causing them harm, we must listen to and believe what is being shared. As a white teacher, it is not my job to argue whether or not the lived experiences of my students are valid. It is my job to hear what is being said and simply value it while I reflect and rethink the choices I make in own practice.

Upon reading the articles above and seeing a larger conversation developing on Twitter, I felt compelled to share my initial response.

I soon noticed an increasingly personal and divisive tone arising in much of the dialogue in the Twitter threads and some mainstream media articles. Defense of the book as essential reading for all seemed to focus on the need for white nostalgia or historical context for a time that most teachers working today have no recollection of whatsoever. The students seemed to be completely removed from the conversation.

If the library is the hub of literacy and learning in our school communities then we must also be at the forefront of valuing student voice and fostering equitable practices throughout.

I started to consider the role of the school library learning commons in this discussion. If the library is the hub of literacy and learning in our school communities then we must also be at the forefront of valuing student voice and fostering equitable practices throughout. The deconstruction of the single story narrative must be a priority in our collection management and our collaborative instruction.

So here are a few of the ideas I came up with:

- Acknowledge my privilege—whenever I can, step aside and amplify the voices of others.

- Listen—to kids, parents, staff and community members and do not explain away someone else’s lived experience.

- Speak out—staying silent implies that I either have no opinion or, worse, that I am complicit in oppressive systemic structures. (If I make a mistake, take the feedback to heart, learn from it and do better.)

- READ, READ, READ – when concerns arise about outdated or harmful texts the more alternatives I can offer to staff and students the better. (Check out Twitter hashtags #ownvoices and #WeNeedDiverseBooks for ideas.)

- Value kids MORE than books—no, I am NOT advocating for book banning but REQUIRING a student to read and analyze a book in order to receive marks and evaluation of their literacy skills and critical thinking is an exertion of power and privilege. This responsibility cannot be taken lightly.

- It’s NOT about me—this is not a personal attack on the books I may have read as teenager or a child.

My hope is that the public conversation can shift to one that centres around student voice, empowers educators to take risks, and increases the value of modern authors and their books to the centre of our classrooms. Even more important is that the conversation leads to conscious actions that elevate the work of racialized authors everyday in library learning commons and literacy programming. The reality is that saying I am an ally is not enough. Ally as a noun is merely a label that I can give myself to appease my own feelings about privilege and power. Ally as a verb means that the actions I take make room for the voices and lived experiences of others each and every day.

Canadian writer and broadcaster Jael Richardson has come up with a list of suggested reads to get people thinking about the different voices and perspectives we can explore through reading.

For themes related to To Kill a Mockingbird

- Brother by David Chariandy

- Washington Black by Esi Edugyan

- Book of Negroes by Lawrence Hill

- American War by Omar El Akkad

- Harlem Duet by Djanet Sears

Books for Grade 9s

- Marrow Thieves by Cherie Dimaline

- The Reckoner Trilogy by David A. Robertson (Strangers, Ghosts, Monsters)

- Saints and Misfits by S.K. Ali

- Prairie Ostrich by Tamai Kobayashi

- The Outside Circle by Patti Laboucane Benson

Photo credit: Annie Spratt on Unsplash

Jennifer Brown, Teacher Librarian, works at the Castle Oaks Public School in the Peel District School Board and currently serves as OSLA vice-president. Jenn can be reached at jennifer.m.brown@peelsb.com and by following her Twitter account @JennMacBrown